Tasting Chambourcin: Part 2

By: Denise M. Gardner

In last week’s post, I described a series of perceptions and observations associated with Chambourcin as a wine grape variety and as a wine. Many growers and producers have chimed into the discussion, and can be viewed in the “Comments” section to the left of the previous blog post.

This week’s post will feature some production options associated with producing a dry to off-dry, red Chambourcin-based table wine.

Producing Chambourcin Wine

From a production standpoint, Chambourcin has the potential to produce several styles of wine:

- Low- to medium-bodied dry red wine

- Semi-sweet to sweet red wine

- Dry to semi-sweet rosé (although the color can be tricky to control or alter)

- Sweet blush

- Sparkling

- Used as a base for formula wines

For the purpose of this post, let us focus on red wine production of Chambourcin. There are a few considerations that growers and winemakers can take when improving the quality of their Chambourcin wines.

Reducing the Perception of Acidity

Getting the TA at or slightly under 6 g/L of tartaric acid, may be a goal for this variety to reduce the perception of sourness in the wine. If the winemaker is opting to make a sweeter red wine with this variety, the higher TA can lead to a sweet-tart sensation on the palate that may be undesirable for some consumers. As a dry wine, a higher TA will make the wine seem more acidic and thin, emphasizing a lighter-bodied wine. While it is not discussed in the academic literature, the acidic-nature or sourness of a wine is what often turns consumers off from some wines produced in the eastern U.S.

Acidity can be managed in the vineyard through proper canopy management techniques and emphasizing the growth of a balanced vine. While I am not a viticulturist, many producers that minimize the sour perception end up dropping fruit (crop thinning) during the growing season to obtain optimal maturity and ripeness later in the growing season. For the most part, Chambourcin tends to be later ripening. At Penn State, we often bring in our Chambourcin when we bring in the Cabernet Sauvignon or after we bring in the Cabernet Sauvignon, making it one of our latest arrivals to the processing floor.

Additionally, acidity can be manipulated in the cellar. While the pH should be optimal for color extraction, the TA can also be altered in the juice and wine phase through potassium carbonate or calcium carbonate additions. De-acidification is tricky; it requires some patience, time, and skill to get used to doing, but it is not an impossibility for many wineries to utilize in the cellar.

Understanding acidity requires a basic understanding of chemistry. There are many educational options available for wineries to better improve their wine chemistry knowledge:

- Utilize the Harrisburg Area Community College (HACC) online viticulture and enology classes. HACC offers an Associate’s Degree in Viticulture and Enology, and all of the classes are available online. Classes were designed and structured for Pennsylvania-based wineries and employees that were looking to change careers into the local wine industry. The HACC classes offer a good educational opportunity for many currently in, or thinking about getting into the industry. Students whom have gone through the program have had positive experiences that they have found invaluable in multiple ways. For more information, please refer to this website: http://www.hacc.edu/ProgramsandCourses/Courses-and-Programs-Details.cfm?prn=1865

- Participate in Cornell’s EnoCert Program. Cornell Extension now offers a certification program specific in viticulture and enology education. It is designed to help enhance an individual’s practical knowledge, and there are many types of 1-2 day workshops, covering a range of topics, that contribute to the EnoCert certification. You can find out more information here: https://grapesandwine.cals.cornell.edu/extension/enocert

- Consider UC Davis’s Online Winemaking Certification. UC Davis also offers an online certificate option. Much of the information can be utilized in cellars here in the eastern U.S. and covers a lot of basic winemaking principles. For more information, please go here: https://extension.ucdavis.edu/areas-study/winemaking/winemaking-certificate-program

Watch YAN during Primary Fermentation

My individual experiences with Chambourcin have included variable yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN) concentrations ranging from 130 – 419 mg N/L in any given harvest year with fruit coming from the same vineyard site. For many nutrient suppliers, a YAN concentration greater than 250 – 300 mg N/L is considered a “high YAN fermentation.” Currently, most recommendations consider YAN concentrations of 150 – 250 mg N/L ideal.

High YAN fermentations can cause problems for winemakers, and has previously been discussed in the following documents:

- Problems and Solutions Associated with High YAN Fermentations

- Nutrient Management During Fermentation

The most common problems associated with a high YAN is the risk of producing hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and/or having a very hot, quick fermentation. In some situations, a hot, quick fermentation may be desirable. However, many hot fermentations may lead to a loss of aromatic or flavor components, which would not be desirable when trying to produce a fruit-forward style of red wine.

It is recommended that wineries find a way to measure the YAN concentration every year for every fermentation. The reason for this is that YAN concentrations are incredibly variable and current research has not been able to correlate vineyard management decisions or parameters with YAN concentrations in the fruit. A small summary of variable YAN in PA and NY vineyards can be found here: Why Measure YAN? Variation in YAN Data Over a 6-Year Time Frame.

If a winery cannot afford to run YANs in-house, there are several available options:

- Ship 50-mL juice samples overnight to an ISO-accredited laboratory when grapes are brought into the crush pad. The laboratory will have the juice sample analyzed by the next business day, which gives the winemaker plenty of time to make an appropriate nitrogen addition at 1/3-sugar depletion of primary fermentation.

- Worried about shipping juice samples to California? Not to worry! Many states (or neighboring states) offer YAN evaluation as part of their analytical services to a multitude of winery clients.

- Cornell University has recently suggested that wineries can receive a representative YAN concentration with an adequate berry sample up to 2 weeks before the grape variety is harvested: Page 3, “Results from 2010,” #2. This may save the winery on shipping costs and give the winemaker a YAN value before the grapes reach the crush pad, allowing for full preparation for nitrogen adjustments.

Measuring YAN and treating the must according to its nitrogen requirements not only minimizes the risk of producing off-aromas associated with hydrogen sulfide production, but in keeping the wine cleaner, it can contribute to a better representation of varietal character. Additionally, it saves labor costs and time associated with treating wines with hydrogen sulfide or a reductive character later on in the winemaking process.

Enhancing Red Fruit Aromas and Flavors

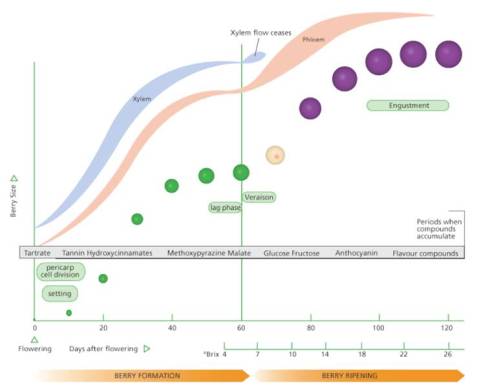

While the mouthfeel of Chambourcin can be easily manipulated, the aromatic intensity and structure can be a bigger challenge. First and foremost, the grapes must be optimally flavor ripe. This is one of those varieties that you want to pick after it reaches 21°Brix. The reason for this is due to the fact that aromas mature after sugar accumulation starts to plateau. B.G. Coombe coined the accumulation of aroma compounds in wine grape berries as the engustment phase of berry ripening (Coombe and McCarthy, 1997; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chemistry effects of berry ripening. Image is from Jordan Koutroumanidis (Winetitles), and previously featured in “Understanding Grape Berry Development” by James Kennedy, Practical Winery & Vineyard Journal (July/Aug 2002)

There are ways that growers and winemakers can become better associated with engustment. The easiest way is to get familiar with berry sensory techniques. Berry sensory analysis goes beyond watching Brix and pH, and enhances the probability in picking grapes when they are flavor ripe. If you feel uncomfortable with this practice, luckily, Lallemand is hosting international wine consultant, Dominique Deltei, at the Vineyard at Grandview (Mount Joy, PA) on Thursday, July 29th from 9:00 AM – Noon. Dominique will discuss how to utilize berry sensory analysis for picking decisions. This is a FREE workshop for those that attend, but space is limited to 15 industry members. You must register with Denise (dxg241@psu.edu) in order to reserve a seat at this workshop.

Enhancing fruity flavors is also a component in wine processing. Many red fermentation gets hot, which can lead to a lot of aromatic blow off during primary fermentation. Practices like:

- Using temperature control or temperature controlled tanks to lower the primary fermentation temperature in order to preserve the aromatic nuances,

- Utilizing 3-4 punch downs or pumpovers per day to maximum extraction and oxygen integration,

- Using red wine yeasts that better express red fruit flavors, or

- Practicing delestage (rack and return) techniques that have been shown to help enhance the fruity characters of red wines

can help maintain fruitiness, which gives producers options in terms of what style of red wine they would like to produce.

Improving the Tannin Structure of Red Hybrid Wines

Many winemakers add exogenous tannins to red hybrid wines despite the scientific evidence that shows it may not be useful. Dr. Sacks’ lab is currently working on ways to improve tannin concentrations in hybrid red wines and has suggested the following technique to commercial wineries at this time:

- Crush and destem the fruit.

- Separate the juice from the pomace. Retain both components.

- Treat the juice with 1.25 g/L of bentonite. Rack.

- Return the juice to the pomace and inoculate for primary fermentation. Make any desired exogenous tannin additions.

- Complete primary fermentation and press wine off of the skins. Make any desired exogenous tannin additions from this step forward.

As Dr. Sacks’ has pointed out: if a winemaker would choose to follow these steps, it does not remove all of the proteins available in the juice/pomace. However, it does remove some of the proteins that could otherwise bind available tannins. Additionally, making exogenous tannin additions after treating juice with bentonite would likely make the tannin addition more effective. Nonetheless, it should be noted that this is a rather labor-intensive cellar procedure. However, it does offer a potential option for those producers looking to increase tannic strength.

As a winemaker, do you have any other recommendations for enhancing Chambourcin wine quality? If so, please add your recommendations or experiences in the Comments section to the left of this blog post title. We would love to hear from you!

Resources

Coombe, B.G. and M.G. McCarthy. 1997. Identification and naming of the inception of aroma development in ripening grape berries. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 3:18-20.

Harbertson, J.F., R.E. Hodgins, L.N. Thurston, L.J. Schaffer, M.S. Reid, J.L. Landon, C.F. Ross, and D.O. Adams. 2008. Variability of tannin concentration in red wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 59:210-214.

Mansfield, A.K. January 2015. A few truths about phenolics. Wines & Vines.

Robinson, J., J. Harding, and J. Vouillamoz. 2012. “Chambourcin.” pg. 218-219. Wine Grapes. ISBN: 978-0-06-220636-7

Springer, L.F. and G.L. Sacks. 2014. Protein-precipitable tannin in wines from Vitis vinifera and interspecific hybrid grapes (Vitis ssp.): differences in concentration, extractability, and cell wall binding. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62(30):7515-7523.

My biggest improvement in making Chambourcin wine has been to limit production to one cluster per shoot. With the large cluster size and weight, one cluster is equivalent or higher in weight than two clusters of vinifera. Also, something I am going to try this year is to immediately press after crush and bleed off a portion for rose wine and return the skins to the main lot for fermentation with the skins. Another option is, depending on the timing of your other harvest, is to add the pressed skins of some vinifera, such as Cabernet Sauvignon to the Chambourcin crush and ferment the Chambourcin with the skins of the vinifera. In short, limit production to one cluster per shoot and let it hang long has worked for me so far and I like my Chambourcin better than most of my vinifera.

Thank you for this insight, Paul! We really appreciate your suggestions, and these are great ideas.

Chambourcin wants to push 2 to 3 clusters on each shoot. I religiously prune them to 1 cluster per shoot and remove any fruit (or entire shoot) that just looks to thin or small to support ripening of the fruit. I also adjust cluster size on smaller shoots. You have to get a feel for what cluster size seems right for the shoot. You will ripen fruit quicker and likely attain much higher brix values especially if warm weather continues through early fall. Don’t be fooled by brix alone. I often drive sugar to 25 brix but that doesn’t mean they’re ready to pick. They need to hang for proper balance in order to get that acidity in check. Still IMHO its not the best for making a single varietal wine. I use it primarily in red blends and its deep purple color is one of the reasons.

One important aspect of Chambourcin is its large berry size and consequent high juice yield. Typically, I’ve gotten yields of 170-180 Gallons per ton from berries that were ~3g. To get numbers more in line with traditional wine grapes, one technique would be a bleed or saignée.

One of the best lots in terms of fruit character and full body was achieved by bleeding off 30 Gallons per ton of juice for a light rosé (resulting in ~140G/ T red wine yield, more in line with vinifera reds.)

This is great advice! Thank you for sharing.

One of the challenges with making a full-bodied Chambourcin is from the high juice-to pommace ratio for such a large-berried variety.

I’ve had success with bleeding off 30 Gallons of rosé per Ton of Chambourcin (with about 140-150 Gallons per ton of red wine yield, more in line with viniferas.)

Higher Total Acidity can easily be adjusted in the cellar by: amelioration, yeast choice (some can convert 40% Malic to ethanol, “C”, 71B) complete MLF, cold-stabilization and blending, just to name a few. I hope winemakers will choose a number of methods in combination, in my opinion, carbonates can alter/mute aromas and mouth feel. If you are going to use a carbonate, use it early (before fermentation) and no more than 1 gram per liter.

From Len Majdan: As Paul Lehmann says one cluster per shoot works. I pinch out at flowering to ensure the vine doesn’t waste energy on unwanted fruit. Also important is not allowing too many bunches per vine. This is based on the age and vigor of each vine – I go by feel. 3 days at 0 Celsius straight after crush to help skin breakdown. In good years 10-20% whole bunches for added tanins. I take off 10% of the juice after it has a bit of colour which provides a decent Rose. But unlike Paul Lehmann I don’t press just drain. Fermentation at 30 Celsius. Finally, 20-23 days on skins after fermentation before pressing to convert those short chain tannins to long chains. This regime has produced some pretty good wine. The only other activity to try next vintage is to split the batch in two and ferment one half at a much lower temperature to get better aromatics.