Winemaking in Austria: An introduction and comments from an 8th generation winemaker

By Dr. Helene Hopfer

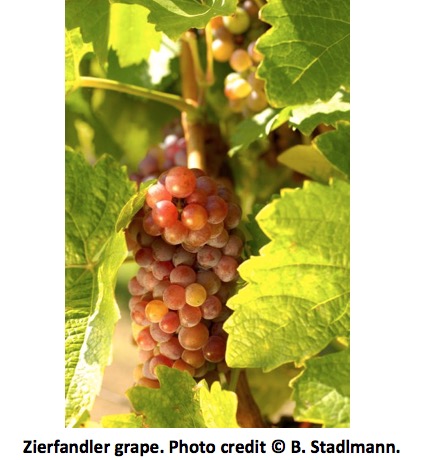

Since starting to work at Penn State last year, I am excited about all these local wines made of Austrian varieties. As a native Austrian, Grüner Veltliner, Zeigelt, and Blaufränkisch (called Lemburger in Germany and Kékfrankos in Hungary) and in particular, the (even) lesser known Rotgipfler, Zierfandler and St. Laurent, are near and dear to my heart (and my palate).

The more I learn about viticulture in Pennsylvania, the more similarities I discover: Similar to Pennsylvania, Austrian growers worry about late spring frosts, fungal pressure and fruit rot, wet summers, and damaging hail events [1]. So it is only fitting to provide some details and insight to Austrian winegrowing and winemaking through this blog post.

Located in the heart of Middle Europe, the Austrian climate is influenced by a continental Pannonian climate from the East, a moderate Atlantic climate from the West, cooler air from the north and an Illyrian Mediterranean climate from the South. Over the past decades, the number of very hot and dry summers is increasing, leading to more interest in irrigation systems, as on average the annual average temperature in Austrian wine growing areas increased between 0.3 to 1˚C since 1990 [2].

Austrian wine growers also see a move towards larger operations: Similar to other wine regions in Europe, the average vineyard area per producer is increasing, from 1.28 ha / 3.16 acres in 1987 to 3.22 ha / 7.96 acres per producer in 2015. Many very small producers who often run their operations besides full-time jobs are now selling grapes or leasing their vineyards to larger wineries. A similar trend is true for wineries [2].

Different to other countries where widely known varieties like Chardonnay or Pinot noir make up the majority of plantings, the most commonly planted grape varieties in Austria are the indigenous Grüner Veltiner (nearly 50% of all whites) and Zweigelt (42% of all reds), followed by the white Welschriesling and the red Blaufränkisch (Lemburger). Another interesting fact is that over 80% of all planted vines are 10 years or older, with 30% of all vines being more than 30+ years old [2].

The Austrian wine market is very small on a global scale, with just over 45,000 hectares / ~ 112,000 acres of planted and producing vineyards by around 14,000 producers nation-wide [2]. Nevertheless, Austrian wine exports are steadily increasing, particularly into countries outside of the European Union, such as the USA, Canada, and Hongkong, indicating a strong interest in this small wine-producing country. Austrian wines are considered high quality, attributable to one of the strictest wine law in the world, the result of the infamous wine scandal of 1985 [3]. Today, the law regulates enological treatments (e.g., chaptalization, deacidification, and blending), levels and definitions of wine quality (e.g., the “Qualitätswein” designation requires a federal evaluation of chemical and sensory compliance), and viticultural parameters such as maximum permitted yield of 9 tons/ha or 67.5 hL/ha and permitted grape cultivars (currently 36 different varieties) [4].

One of the leading figures in developing the now well-established Austrian wine law was Johann Stadlmann, then president of the Austrian Wine Growers’ Association. During his 5-year tenure starting in 1985 at the peak of the wine scandal, he made sure that the wine law could be implemented in every winery and ensured strict standards; Johann Stadlmann could be called the father of the Austrian ‘Weinwunder’ (=’wine miracle’), the conversion of Austria as a mass-producing wine country to one with an emphasis on high quality.

Weingut Stadlmann – an estate with a very long history

If you ever visit Austria, you most likely fly into Vienna, the country’s capital. Vienna is one of the few cities in the world that also has producing vineyards located within city limits. Just outside of the city limits to the South, lies another important wine region in Austria, the so-called ‘Thermenregion’, named after thermal springs in the region. The region has a long wine history, dating back to the ancient Romans, and later Burgundian monks in the Middle Ages. The region is characterized by hot summers and dry falls, with a continuous breeze that reduces fungal pressure. One of the leading producers within the region is the Weingut Stadlmann, dating back to 1778 and now run by the eighth generation, Bernhard Stadlmann. He is the latest in a line of highly skilled winemakers that combine innovation with a conservative approach. His grandfather, Johann Stadlmann (yes, the same guy of the Austrian wine law), was one of the first ones in Austria to use single vineyard designations on his wine labels. Bernhard’s father, Johann Stadlmann VII, a master in creating wines from varieties only grown in this region, and named ‘winemaker of the year’ in 1994, is known for his careful approach and is now working alongside his son, Bernhard. In 2007, Bernhard started the conversion of the family-owned vineyards to certified organic. The family cultivates some of the best vineyards in Austria, including the single vineyard designations ‘Mandel-Höh’, ‘Tagelsteiner’, ‘Igeln’, and ‘Höfen’, planted with the indigenous varieties Zierfandler and Rotgipfler only grown here in the region. Wines from these vineyards are among the very best Austria can offer!

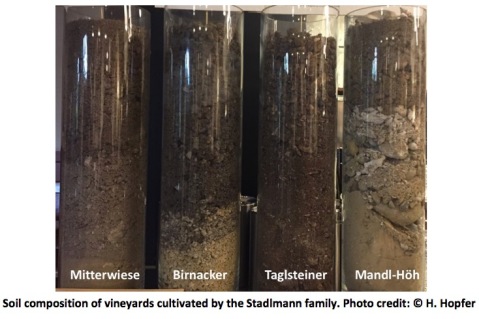

The vineyards cultivated by the Stadlmann family also differ quite dramatically in soil composition: While the ‘Mandel-Höh’ vineyard is highly permeable to water and nutrients, with lots of ‘Muschelkalk’ (limestone soil formed of fossilized mussels shells), is the ‘Taglsteiner’ vineyard characterized by more fertile and heavier ‘Braunerde’ soil, capable of retaining more water.

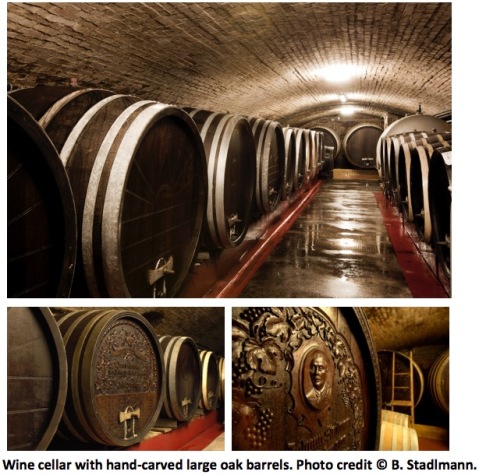

The long winemaking history becomes apparent once one steps into the wine cellar, full of large barrels, made of local oak: Some of these barrels have hand-carved fronts, depicting their vineyards and Johann Stadlmann senior. All of these barrels are in use, and part of the Stadlmann philosophy of combining tradition with innovation.

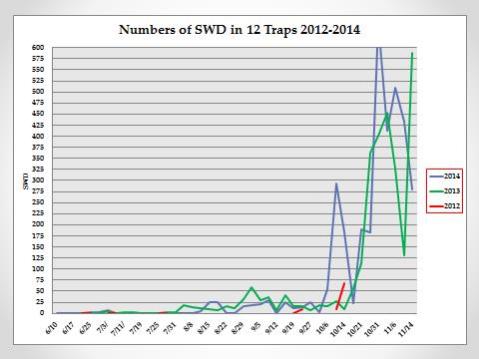

Another increasing threat is the spotted wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii, damaging ripening grape berries from véraison onwards. Bernhard sees some varieties more affected by Drosophila suzukii than others. There is intensive research on pest control, including shielding nets, fly traps, and insecticide strategies, and the Stadlmanns currently run experiments within their organic program: They blow finest rock flour (Kaolin and Dolomite rock) into the leaf canopy and fruit zone to create unfavorable conditions for different insects, including Drosophila, wasps, which pierce sweet berries, earwigs and Asian lady beetle, both leafing residuals causing off-flavors in the wine once they’re crushed. Drosophila suzukii was first discovered in Austria a few years ago and is also an issue in the US (see also Jody Timer’s blog post).

During a recent visit at the Stadlmann estate, I had the chance to chat with Bernhard about the challenges of Austrian winegrowing and winemaking. I was interested in a young winemaker’s perspective, especially as Bernhard has been trained all around the world, including Burgundy, Germany, and California. This year, spring frost in late April threatened vineyards in many winegrowing regions in Austria, requiring the use of straw bales and paraffin torches to produce protective and warming smoke. Luckily, not too much damage was done to the Stadlmann’s vineyards, however, it caused some sleepless nights for Bernhard and his family, and shows also the importance of developing effective spring frost prevention alternatives (see also Michela Centinari’s blog post).

We also talked quite a bit about wine quality: while the Austrian ‘Qualitätswein’ designation ensures basic chemical (e.g., ethanol content, titratable and volatile acidity, residual sugar, total and free SO2, malvidin-3-glucoside content (for reds), etc.) and sensory (i.e., wine defects like volatile acidity, Brettanomyces, atypical aging, mousiness and other microbial defects) quality, this only ensures a lower limit of quality. In the recent years, the Austrian governing bodies added another layer of wine quality, based on the Romanic system of regional typicity and origin: The so-called DAC (Districtus Austriae Controllatus) wines are quality wines typical for a region, made from varieties that are best suited for that region. DAC wine producers adhere to viticultural, enological, and marketing standards, with the goal to establish themselves as famous wines of origin (think Chablis, Cote de Nuits, Barolo, Rioja or Vouvray). As this is a relatively new system for Austria, we will see how successful these DAC regions will be. Their success will also depend on the regional producers, and how stringent they set the criteria for the DAC designation, as they have to walk a fine line between establishing a recognizable regional typical wine without losing individual character that each producer brings to their wines.

If you are interested in learning more about Austrian wines, and Bernhard and his family’s wines, they were recently highlighted in a couple of US wine publications, including a great podcast episode on ‘I’ll drink to that!’ and an article in the SOMM journal about Zierfandler. Zierfandler is one of Stadlmann’s signature varieties, indigenous to the region, but tricky to grow, as it requires long and dry ripening periods and has a very thin skin, prone to botrytis. However, when done well (like the Stadlmanns do), it produces extraordinary wines with fruity, floral, and sometimes nutty notes that have a long aging potential. If you are able to get your hand on these Zierfandler wines get them while you can!

Last, a big Thank You to Bernhard Stadlmann for his help with this blog post: He took time out of his super busy harvest schedule to show me around, never getting tired of answering my questions. He also graciously provided all but one of the pictures.

References

[1] Huber K (2017) Durchschnittliche Weinernte 2017 erwartet. LKOnline. Available at (in German): https://noe.lko.at/weinbau+2500++2455141

[2] Austrian Wine Marketing Board (2017) Austrian Wine Statistics Report 2015. Available at (in German): http://www.austrianwine.com/facts-figures/austrian-wine-statistics-report/

[3] New York Times (1985) Austria’s Wine Laws Tightened in Scandal. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/1985/08/30/world/austria-s-wine-laws-tightened-in-scandal.html

[4] Austrian Wine (2017) Wine Law. Available at: http://www.austrianwine.com/our-wine/wine-law/

Tasting Chambourcin: Part I

By: Denise M. Gardner

Note: Sensory descriptions of wines produced by the grape variety, Chambourcin, are based on individual observations, tastings, and a collection of notes obtained through various Chambourcin tastings including many different individuals.

At the Central Pennsylvania regional winery meeting held at Brookmere Winery, attendees and I had the opportunity to taste through a series of Pennsylvania-grown and produced Chambourcin wines. This was actually one of the first all-Chambourcin wine flights that I have been able to taste, and I was quite encouraged by what I was tasting in the glass. Paula Vigna, writer for The Wine Classroom via Penn Live, has since written an article on the tasting titled, “Chambourcin’s ceiling: Maybe higher than originally thought.”

Chambourcin: A Description

Chambourcin is a French-American hybrid wine grape variety that was bred by crossing Seyve-Villard 12-417 (Seibel 6468 x Subéreux) with Chancellor*, commercialized in 1963 (Robinson et al. 2012). Despite Chambourcin’s vigor and relative tolerance to disease pressure in humid climates, anecdotally the wine does often appear preferred by many Vitis vinifera winemakers.

As a wine, Chambourcin’s strength is its vibrant red color and supple, soft mouthfeel due it is relatively lack of course tannin on the palate. These features often make it a valuable red wine blending possibility, especially considering the relative consistency of obtaining Chambourcin fruit every vintage. However, the smoothness of the wine often is a frustration by many eastern winemakers looking for more depth and [tannin-related] mouthfeel in their red wines. When coupled with Chambourcin’s notorious ability to retain acidity, often above 7 g/L of tartaric acid (depending on where and how it is grown), the lack of perceived tannin can make the wine taste relatively thin and acidic.

The acidity associated with the Chambourcin grape variety often appears retained when grown in cooler climates. For example, in Pennsylvania, Chambourcin produced in North East, PA (Erie County) often has relatively higher TAs compared to Chambourcin grown in southeastern, PA (e.g., Berks County). From a grape growing perspective, all winemakers should expect this phenomenon. However, Chambourcin can retain a higher acidity even when grown in the warmer southern parts of Pennsylvania. Based on observation, the variety seems to maintain its acidity when it is not thoroughly crop thinned. As Chambourcin is an incredibly vigorous variety, and as you will see from the tasting, producers hoping to drop the acidity often crop thin grape clusters while on the vine.

When looking at the tannic composition of Chambourcin, it is likely that much of the tannin content associated with Chambourcin is lost during primary fermentation. Dr. Gavin Sacks at Cornell University is studying this situation associated with many hybrid wine fermentations. As Dr. Sacks discussed at the 2016 Pennsylvania Wine Marketing & Research Board (PA WMRB) Symposium in March, tannins come from 3 different components of the grape: the stems, the skin, and the grape seeds. During the fermentation process, anthocyanins (red pigments) and skin tannin is extracted quickly, usually before the product starts to ferment. Seed tannin is extracted more slowly, typically throughout primary fermentation and extended maceration processes. Dr. Sacks’ lab (Springer and Sacks, 2014) and previous research (Harbertson et al. 2008) have shown, grapes produced outside of the western U.S. generally have lower concentrations of tannin available in the grape. While available tannin in the grapes does not necessarily correlate with tannin concentrations in the finished wine, many eastern U.S. winemakers will add exogenous tannin pre-fermentation, during fermentation, and/or post-fermentation to help improve mouthfeel and potentially increase substrate availability for color stability reactions. However, even with exogenous tannin additions, Dr. Sacks has found that many of the tannins associated with hybrid fermentations end up lost during the fermentation process due to protein-tannin binding complexes that pull tannins out of the wine. The higher protein concentration associated with the hybrid grapes has been linked to disease resistance mechanisms that the varieties were originally bred for, and is more thoroughly explained in Dr. Anna Katharine Mansfield’s recent Wines & Vines article, “A Few Truths About Phenolics.”

Additionally, Chambourcin has been noted to have a relatively neutral red wine flavor, lacking a concentrated pop of fruit and using non-descript aromatic or flavor descriptors like: red cherries, red fruit, red berries, stemmy, herbal, or even millipedes. And yes, I have heard one or two consumers actually reference a millipede aroma when tasting Chambourcin.

Tasting Chambourcin Produced in PA

Figure 1: Flight of Chambourcin Wines tasted at the June 2016 Central PA Regional Wine Meeting, hosted by Brookmere Winery. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

The official flight (Figure 1) of Chambourcin wines that I had put together included:

- Galen Glen Winery 2014 Stone Cellar Chambourcin

- Penns Woods Winery 2014 Chambourcin Reserve

- Vynecrest Winery 2014 Chambourcin

- Pinnacle Ridge Winery 2013 Chambourcin Researve

- Allegro Winery 2012 Chambourcin

Additionally, Brookmere Winery, Armstrong Valley Winery, and Caret Cellars (Virginia) added Chambourcin wines to taste. The formal wine tasting turned out to be quite a unique experience.

I saw a few over-arching sensory themes within these wines:

- Reduced acidity: While I did not personally measure the pH and TA for these wines, the perception of acidity was not as obvious, overly perceptible, or offensive.

- Soft, supple mouthfeel: Even with a couple of the wines that were perceived as “more tannic,” these wines were soft and easy-drinking.

- Use of oak barrels: Many of the producers were opting for some production in actual oak barrels as opposed to using oak alternatives. Type of oak ranged from French, American, and Hungarian.

- Higher alcohols: Alcohol concentrations for these wines ranged from 13-14%, likely due to extended hang time in the vineyard, allowing for an increase in sugar accumulation.

- Two emerging aromatic profiles: A couple of the wines were very fruit-forward and fruitier than what is normally expected from Chambourcin. The other wines were less fruit-forward, however, they did retain a fair amount of red fruit aromatics in addition to the complex aroma nuances: earthiness, tobacco, toasted oak, vanilla, and tobacco. Many tasters commented on the general concentration of aromatic nuance associated with many of the wines we tasted.

In general, the relative depth, cleanness, and fruit expression of these wines was impressive. Perhaps this tasting clearly indicated that although many winemakers struggle with finding the “right fit” or style for their Chambourcin, the level of quality associated with the wine has definitely improved within the last 5 years. At the very least, the level of quality associated with this flight of wines was encouraging for hybrid red wine producers.

Additionally, Brookmere Winery provided a real treat from their cellar library: a 1998 Chambourcin produced by Brookmere Winery (Figure 2) when Don Chapman owned the winery. If you appreciate older wines, then this Chambourcin would truly impress you. Not only did it express the “old wine” honey-floral character loved by many wine enthusiasts, but the red fruit aromas and flavors were still boldly expressed in the wine. The color was intense and dynamically red, and there was a fine perception of firm tannins on the palate. Overall, the tasting of this wine gave me the perception that not only did this wine still have plenty of room to continue aging in the cellar, but that Chambourcin, as a wine varietal, had positive potential for aging for more than 10 years.

Given that most of this post is based on my own experiences, perceptions, and information gathered from growers and producers pertaining to Chambourcin, I would welcome any additional experiences with the variety (as a grape or as a wine) in the comments section.

While this post has documented Chambourcin as a grape variety and a small snap shot of sensory perceptions from a handful of producers in Pennsylvania, next week’s post will focus on production techniques to improve the quality Chambourcin red wines.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

For more information on upcoming regional meetings and the types of tastings to be held at those FREE events, please visit: http://extension.psu.edu/food/enology/events

- Northwestern PA (Erie County) – Individual Site Visits

- Southwestern PA (La Casa Narcisi Winery) – Talk on High Potassium Winemaking

- Southeastern PA (Vineyard at Grandview) on Thursday, July 28th – Berry Sensory Training hosted by Lallemand, with international wine consultant Dominique Deltei (Must register with Denise (dxg241@psu.edu) as space is limited to 15 people.)

Resources

Harbertson, J.F., R.E. Hodgins, L.N. Thurston, L.J. Schaffer, M.S. Reid, J.L. Landon, C.F. Ross, and D.O. Adams. 2008. Variability of tannin concentration in red wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 59:210-214.

Mansfield, A.K. January 2015. A few truths about phenolics. Wines & Vines.

Robinson, J., J. Harding, and J. Vouillamoz. 2012. “Chambourcin.” pg. 218-219. Wine Grapes. ISBN: 978-0-06-220636-7

Springer, L.F. and G.L. Sacks. 2014. Protein-precipitable tannin in wines from Vitis vinifera and interspecific hybrid grapes (Vitis ssp.): differences in concentration, extractability, and cell wall binding. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62(30):7515-7523.

*Authors Note: Since the publication of this article, a few growers and grape breeders have alluded to the improperly reported parentage of Chambourcin. While it is generally reported and cited as such, it is understood among some wine grape experts that Chancellor is not likely a parent to Chambourcin. For more information on determining parentage of given grape cultivars, please refer to: http://www.vivc.de and search the cultivar name of interest.

Regional Winery Meetings Scheduled for Pennsylvania Wineries in Summer 2016

By: Denise M. Gardner

Each calendar year, Penn State Extension works with the state wine industry to schedule “regional” meetings with local producers.

Regional meetings are kindly and financially supported by the PA Wine Marketing and Research (WMRB) Board and Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA), as part of the annual operating expenses that are granted to the Penn State Extension Enology position each fiscal year. The financial support is, in part, contributed by each Pennsylvania winery in the annual assessment on the gallons of wine produced across the state, which are submitted to the PA WMRB. It is this funding mechanism that makes these visitations possible on an annual basis, and all Pennsylvania wineries are encouraged to attend.

These regional visitations by the Extension Enologist were designed to be convenient for local industry members in terms of location. While industry members, or perspective industry members are welcome to attend any of the meetings, the purpose of these meetings is for me to get out into various parts of the state while making traveling a bit more convenient for industry members.

Regional meetings are free for industry members or prospective members to attend.

All regional meetings are hosted at a local winery, and meeting locations are listed below and on the Penn State Extension Enology website.

Each region organizes their regional visits differently, and they are designed to be beneficial for that region of industry members.

Regional meetings all have a unique structure. Many are only a few hours long, offer a production tour of a local winery, and many include a tasting. In the past, regional meetings have included anything from question and answer sessions on a production tour:

Denise Gardner discusses winemaking with Sharon Klay from Christian Klay Winery. Photo from: Mark Chien

To tasting bench trials created by some of the local wineries:

To hosting benchmark tastings on specific wine varieties:

To holding a short educational program on a topic of specific interest to that region.

Dr. Kathy Kelley presents her research on tasting room design at a regional meeting in Erie County. Photo from: Denise Gardner

Additionally, these visitations by the Extension Enologist offer several benefits to the local industry, including:

- meet with existing producers to discuss potential problems or challenges within the winery,

- visit with potentially new or new producers within the wine community,

- introduce new producers to existing operations to enhance networking and collaboration across the state,

- answer questions pertaining to wine production and quality, and

- review Penn State research updates pertinent to the wine community.

The tentative agendas for each regional meeting, in addition to their scheduled date, for 2016 are listed below.

- Central PA: Thursday, June 16th, hosted at Brookmere Winery

The program at Brookmere will include a production tour with a question and answer period by all attendees. Additionally, Denise will conduct an educational tasting on local Chambourcin wines produced across Pennsylvania. This was created by request from the regional producers in order to get a better idea of how Chambourcin tastes throughout the state.

- Northwestern PA (Erie County): Wednesday, August 3rd – To schedule a winery visit by Denise, please contact Andy Muza to get on the schedule.

This regional visit will follow the day after the “Stabilize Your Wine – Filtration, SO2, and Potassium Sorbate” workshop hosted by Cornell and Penn State Extension at the CLEREL Station in Portland, NY. This workshop requires pre-registration (see the attached link), and anyone is welcome to attend with paid registration.

On August 3rd, Denise will visit individual wineries to discuss winery-specific problems or to keep Denise current on what is happening in the winery. To schedule an appointment with Denise, please contact Andy Muza in the Erie County Extension Office.

- Southwestern PA: Thursday, August 4th, hosted at La Casa Narcisi Winery

The southwestern regional meeting will be held at La Casa Narcisi Winery and include a production tour. Denise will host a small educational session on high potassium winemaking with a tasting of the high potassium wines (i.e., Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon) that were produced by Penn State during the 2015 harvest. Wineries are welcome to bring their own wines for feedback and welcome to stay through lunch, which can be purchased at the restaurant on site at La Casa Narcisi.

- Northeastern PA: Date and location TBD, but please reserve August 30th or 31st on your calendars

Currently, the date and final agenda for the northeastern part of the state is being discussed. But, please continue to check the “PSU Extension V&E News” listserv and Extension Enology website for updates.

More information, and updates, on each regional visit can be found at: http://extension.psu.edu/food/enology/events. Pre-registration is NOT required for anyone to attend regional meetings.

While there is not a Southeastern PA regional meeting currently scheduled, there are several events hosted in the southeastern section of PA that are conveniently located for those regional wineries. Wine Trails in the southeastern quadrant of PA are encouraged to contact Denise for specific visitations.

The most current workshop on the calendar includes the Sensory Defects for Fermented Beverages and Distilled Spirits workshop, held on June 9th, which will be hosted in Collegeville, PA (Montgomery County). Registration for this workshop is required, and details for the program can be found at the above link.

As is the past, the Penn State Extension Enologist acts as a resource for Pennsylvania wineries when production problems or questions arise. You can find contact information In addition to the list of educational programming designed for the local industry, Penn State Extension is filled with:

- Online resources via Penn State Extension’s website

- The “Wine & Grapes U.” blog site, which includes a yearlong calendar of local/regional/national events and local sales and job opportunities.

- Annual workshops including the Wine Quality Improvement (WQI) Short Course held every January, the upcoming Sensory Defects for Fermented Beverages and Distilled Spirits workshop, the PA Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium, and many additional workshops that cover a multitude of topics. Previous workshop topics covered: micrbiological techniques for wine production, the use of sulfur dioxide in the winery, pre-harvest preparation, benchmark wine tastings, blending, and more!

- Wine Made Easy Fact Sheets, which can now be found on the Extension website! These are quick print outs designed to help winemakers in the winery. Visit the link for all of the topics currently published.

- The weekly “Penn State Extension V&E News” listserv, distributed every Friday to keep industry members current on research, real-time issues in the vineyard and winery, and upcoming events pertinent to this industry.

Technical Information about Pét-Nats (Pétillant Naturels, or Sparkling Wines Produced by Méthode Ancestrale)

By: Denise M. Gardner

Author’s Note: Current technical information regarding the production of pétillant naturels is limited. The following information is summarized and detailed from a series of text books and personal discussions with Paul Guyard from Enartis, Daniel Granes from the ICV in Languedoc-Rousillion, whose contact comes courtesy of Gordon Specht from Lallemand, and Michael Jones from Lallemand. The author would like to thank all contributors for the following information.

The recent interest in sparkling wine production (http://bit.ly/SparklingWineTechniques) has winemakers and sommeliers talking about another trendy bubbly: Pétillant Naturels, or pét-nats when abbreviated. These bubblies are consumer friendly: less expensive than traditional Méthode Champenoise-produced wine, usually contain an enhanced fruitiness, are meant to be consumed early (i.e., no long term aging required by the consumer), and are currently trendy amongst wine professionals, bloggers and sommeliers. A quick search online can lead one to a plethora of articles indicating consumer awareness of pét-nats:

- Pét-Net, Champagne’s Cool Younger Sister, Is the Bubbly You’ll Be Drinking All Summer by Bon Appétit

- Pét-Net, Champagne’s Hip Younger Sister, Hits its Peak Season

- Why You Should Expand Your Sparkling Wine Horizon with Pét-Nat

- 25 Reasons to Drink Pét-Net

Recent food trends indicate that consumers are searching for “more natural” selections (http://fortune.com/2015/05/21/the-war-on-big-food/), and pét-nats may appear as a less intrusive winemaking approach in the eyes of consumers. Pét-nats offer a winery marketing potential, as many are highlight as being made with limited technological influence and following more traditional winemaking practices.

The concept of production is rather simple: start fermentation and bottle before it is finished fermenting to retain some residual carbon dioxide, and likely sugar, in the final product. However, production requires winemaker attention to ensure final wine quality. As David Lynch quoted one producer in his Bon Appetit article, pét-nats production can seem like “Russian roulette winemaking” from the production perspective. Although in French, a detailed diagram displaying the steps of the méthode ancestrale production practices associated with pét-nats (follow the column labeled “méthode rurale”) can be found here: http://www.wine-and-bubbles.com/maj/phototheque/photos/schema/ShemaEtTexteCv4_3.jpg

History of Pét-nats

Pét-nats are believed to be the original source of sparkling wine production in France, preceding Champagne production (Robinson and Harding 2006). It is believed that wines from naturally-cooler regions in France would undergo primary fermentation until the winter when temperatures would naturally drop and inhibit fermentation. Winemakers, unaware that the wine was not fully fermented, bottled the young wine and found that it re-fermented in the bottle when the ambient temperatures became warmer. Some of the first sparkling wines produced have been traced back to Gaillac, located in the southwest part of France, north of Toulouse, and Limoux, located in the higher mountains of the Languedoc-Roussillon region (Robinson and Harding 2006).

The term “pétillant” generally describes a sparkling wine with less retention of carbon dioxide compared to a sparkling wine like Champagne (WSET 2001). The grape variety traditionally used for pét-nat production in Gaillac and Limoux is mauzac (known locally as blanquette in Limoux), which has a distinguishable “dried-apple-skin” flavor (Robinson et al. 2014). Today, pét-nat production has exceeded the boundaries of their origins, extending through the Loire and various regions around the world.

The production method associated with of Blanquette de Limoux is often referred to as the méthode ancestrale, or as the méthode gaillacoise in Gaillac (Robinson and Harding 2006). The methods are quite similar in execution, which consists of one primary fermentation that is started in tank and finished in the bottle. This results in a cloudy wine, typically with varying concentrations of residual sugar, and retention of carbon dioxide.

Thinking of Giving Pét-Nat Production a Try?

While the production of pét-nats may seem appealing, one of the experts suggested trying to bottle condition a wine before attempting the full méthode ancestrale production technique as it involves a lot of winemaker attention. This may also be a practical alternative when current production facilities are not equipped for full-range temperature control. Bottle conditioning is typically used by homebrewers, home cider makers, and home winemakers to get carbon dioxide in bottles. You can read some of the home production literature here if you are unfamiliar with the process:

- Advanced Bottle Conditioning by Northern Brewer

- Bottle Carbonating by Northern Brewer

- Bottle Conditioned Perry and Cider by Welsh Perry and Cider Society

It is recommended that you use a low alcohol (≤12% alcohol v/v), low pH (<3.50) wine if you are exploring the bottle conditioning technique. Add enough sugar to generate 3-4 ATM of pressure, maximum, and bottle with a yeast addition based on the suggestions below. Bottles should be suitable to retain pressure and sealed with a crown cap.

Bottle conditioning a wine should give you a clear indication regarding the finishing technique and style associated with pét-nats. It also acts as good practice before committing to pét-nat production.

Safety First

Since pét-nats are sparkling wine products that contain a fair amount of pressure, winemakers and cellar staff should proceed with caution during production. Use common sense: purchase appropriate bottles made to withstand pressure, double check calculations for sugar-to-pressure conversions, and use protective eye glasses. Accidents can happen, and it is best to be prepared for any hazard associated with any stage of wine production. Sanitation is a key point through production, and proper protective clothing should be worn at all times when using sanitizing agents of any kind.

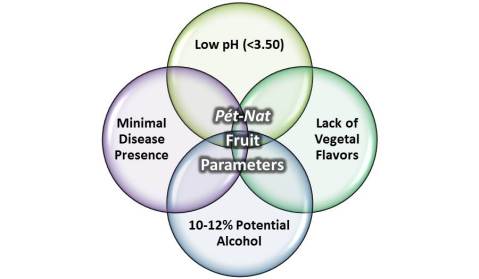

Parameters to Look for in the Fruit

Pét-nat production may be applied to any grape variety, and offers a wide opportunity for winemakers to explore the production of new and unique wine products. Although there are no variety limitations, production experts caution that grapes should lack vegetal flavors in the berries.

Berry sensory analysis may be useful for winemakers to evaluate grape flavor quality and to help determine picking times. In general, ripe (non-vegetal) flavors should persist in the berry in order to encourage their development in the final wine. However, grapes should avoid “overly ripe” flavor characteristics as this may be an indication of higher pH and lower acidity values that may cause complications through the winemaking process.

Grapes are often picked with a potential alcohol of 10 – 12% v/v, and at this concentration of natural sugar, the pH should be lower (<3.50). The pH of the wine will offer microbial protection to the wine through the méthode ancestrale process and offer some protection to wine quality through vulnerable production steps.

Fruit should also be of sound quality (i.e., with limited disease pressure) to avoid detriment to flavor and overall quality of the wine. Some diseases may contribute secondary byproducts which could cause fermentation complications. Therefore, the winemaker is encouraged to use sound fruit. Cellar hygiene, or proper sanitation techniques, will be essential for quality control purposes through production. Extra sanitary care should be taken if the winemaker wants to remove the lees from bottles by traditional disgorging techniques (refer to a previous post on Sparkling Wine Production Techniques). A summary of grape parameters required for pét-nat production is shown in Figure 1.

Base Wine Production

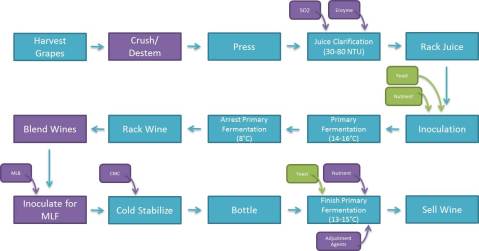

The production method associated with pét-nats (Figure 2) is alluded to rather simply in the wine literature: the primary fermentation is started in tank, arrested before primary fermentation is completed, bottled, and finished in the bottle. The consumer can expect a slightly sweet (i.e., presence of residual sugar), cloudy, lightly bubbled wine (usually below 4 ATM pressure; Amerine et al. 1972). Winemakers should refer to the TTB for additional tax purposes associated with sparkling wines (http://www.ttb.gov/wine/wine_regs.shtml).

Grapes are crushed/destemmed (if preferred) and pressed. In France, press cycles and parameters are based on regulation. Press cycles are set to extract 100 L of juice for every 150 kg of fruit.

Some attention should be given to clarification of the juice, pre-fermentation, in the production process of pét-nats. It is recommended that juice is clarified to 30 – 80 NTUs with use of centrifugation, flotation or assistance with settling enzymes and/or fining agents.

There is some debate as to whether or not sulfur dioxide should be added to the juice during settling. In the juice-settling phase, a sulfur addition may help clarify the juice and minimize spoilage yeast and bacteria that could harm the quality of the wine. However, like with still wine production, sulfur dioxide additions should not be made to excess as too much could hinder primary fermentation. (Note: For those looking to produce a “more natural” wine, or to appeal to the “no-sulfur-added” market, it would be prudent to skip sulfur dioxide additions at this step.)

Following clarification, the juice should be racked and prepared for inoculation.

Starting Fermentation

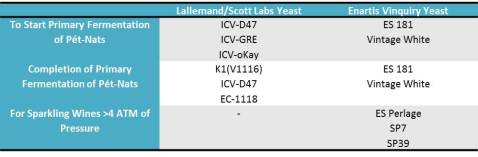

Yeast selections (Table 1) should be based on the winemaker’s preference, but there are some tips that have been provided by wine supply companies:

- Use low-sulfur dioxide-producing yeast strains

- Select yeasts for secondary aroma potential

- Supply yeasts with proper hydration and fermentation nutrient additions

- Use yeasts that grow optimally in cool temperatures, 14-16°C (~57-60°F)

- If the winemaker is going to remove lees (e., disgorging) before selling the product, and is only going to undergo one fermentation without a second inoculation, choose a yeast strain that is recommended for Méthode Champenoise sparkling wine production

Table 1: Yeast Recommendations from Lallemand and Enartis Vinquiry for Pét-Nat Production (Note: Other suppliers may have additional yeast recommendations. Please consult your regular supplier for further suggestions.)

Use a hydration nutrient (e.g., GoFerm Protect Evolution, Enartis Ferm Arom Plus) properly at inoculation. Depending on the winemaker’s preferred techniques or the perceived difficulty of alcoholic fermentation, oxygen additions can be made to activate the fermentation. Some winemakers choose oxygen ingress through the use of micro-ox, and base dosage rates [of oxygen] on sensorial perceptions.

Use of temperature control is essential for producing pét-nats. If you need more information and suggestions regarding how to integrate temperature control into your winery operation, please visit this report here: http://bit.ly/LowTempFerm.

Fermentation should proceed at 14-16°C (~57-60°F). At about +/- 3% v/v from the target alcohol, winemakers should chill the wine down to 8°C (~46°F) to hinder the fermentation. The act of cooling will also clarify the wine and minimize the transfer of lees. Too much lees transfer will result in a “yeasty” flavored wine, which is not preferred in pét-nat wines.

Finishing the Wine

Once the wine is properly chilled, it will need to be racked to remove most of the lees. It is not uncommon for winemakers to remove all of the lees by centrifugation or filtration, and later, restart the wine with a fresh culture and hydration nutrient. From a French winemaking perspective, the addition of nitrogen is usually added at racking in the pump flow (1 L of nitrogen gas for each 20 L of wine).

Winemakers may opt to blend at the racking stage as well. Blending can help elicit the production of a “house-style” pét-nat, and ensure consistency despite natural vintage year variation.

Malolactic fermentation is optional, and should be inoculated after racking, based on winemaker preference. For those that are considering malolactic fermentation, it is important to remember that there is a significant quantity of residual sugar in the wine at this stage in the process, which can lead to a series of winemaking problems:

- Consider the wine’s pH before undergoing malolactic fermentation. Malolactic bacteria have a higher risk of producing more acetic acid during malolactic fermentation if the wine pH is greater than 3.50. Great attention and care must be given to a pét-nat undergoing malolactic fermentation with a higher pH to avoid extreme spoilage issues.

- Malolactic bacteria require a warmer temperature for growth, which requires the winemaker to increase the temperature of the wine. Therefore, it is suggested that winemakers sterile filter the wine prior to inoculating for malolactic fermentation to avoid primary fermentation from re-starting and completing before the wine is bottled.

- The remaining residual sugar puts the wine at risk for other microbial contaminants. Sanitation and monitoring of malolactic fermentation progression is of the utmost importance.

Tartaric acid stabilization, or cold stabilization, can progress at this stage after the wine is racked. However, it is more common for winemakers to add CMC to avoid crystallization of tartaric acid as opposed to undergoing a cold stabilization process.

At this point, the wine should be prepared to complete primary fermentation. If the wine were to go to tank and complete fermentation, then the process of completion follows a Partial Fermentation process that is used in the Asti region of Italy to produce Moscato.

To complete the méthode ancestrale technique, the base wine is bottled to complete fermentation. A second inoculation of yeast is typically required to complete primary fermentation, but it is optional to add more yeast nutrient at inoculation. Some wineries choose a second edition of a hydration nutrient (prepared during yeast hydration) and a smaller dose of a complex nutrient (e.g., Fermaid K, Nutriferm Advance). Yeast addition dosage rate is recommended at about 2 million colony forming units (CFU) per mL of living yeast. Ideally, yeast addition should be less concentrated than a “normal” inoculation to minimize biomass in the bottle and encourage a slow fermentation in the bottle. Yeast strain should be selected according to winemaker preference (see the above list, Table 1, for suggestions from Lallemand/Scott Labs and Enartis Vinquiry).

Méthode ancestrale does not involve a sugar addition at the second inoculation. However, a sugar addition to manipulate the final desired concentration of pressure in the bottle is an option for winemakers at the second inoculation of yeast.

Bottle selection is important, and needs to be of high enough quality to retain the internal pressure left over from fermentation. If the expected pressure is above 4 ATM, ensure that you are using the correct bottles to retain pressure. Yeast selection should also be altered if the final preferred pressure is greater than 4 ATMs.

Although a slight detour from the méthode ancestrale process, it is possible to remove the lees after fermentation has completed in the bottle. If the winemaker would like to riddle and disgorge the yeast at the completion of primary fermentation in the bottle, a riddling agent (e.g., Adjuvant MC by Enartis Vinquiry) may be desired.

After the base wine is re-inoculated in the bottle, bottle fermentation should progress in a temperature controlled space, optimally set at 13-15°C (~55-59°F). For retention of residual sugar, chill the room to 0-2°C (32-36°F) to arrest fermentation in the bottle. [Note: When the wine is warmed up, it may continue to ferment in the bottle.]

With the minimal yeast population, minimal nutrient availability, increase pressure in the bottle, and low fermentation temperature, fermentation will progress slowly and may stop with residual sugar naturally as all of these factors put stress on the yeast. It may take several months until an appropriate amount of pressure has built up in the bottle.

Figure 2: Flow Diagram Representing General Production of Pétillant Naturel Sparkling Wines (Méthode Ancestrale)

Potential Disgorgement

Some winemakers choose to sell a product that is clearer than traditional pét-nats and disgorge the yeast lees using similar techniques that were previously discussed pertaining to the traditional method, Méthode Champenoise, way of making sparkling wine. Here, the lees are collected, riddled, and disgorged. If the wine was fermented to dryness, a sugar addition with a dose sulfur dioxide can minimize risk for re-fermentation when the bottle is in the hands of consumers. Furthermore, disgorgement allows a winemaker to make sensory alterations to the wine with a dosage addition. Sensory adjustments can be made using Arabic gums, inactivated yeast/polysaccharide products, or tannins that have been added to the dosage.

Traditionally, pét-nats are sealed with a crown cap.

Final Production Thoughts

Large producers of bottle conditioned cider may opt to flash bottle pasteurize hard ciders that retain some residual sugar. Flash bottle pasteurization will inactive the yeast and ensure an extra line of protection to ensure that fermentation does not continue to progress once the consumer has purchased the product.

However, part of the fun associated with pét-nats is not truly knowing the end residual sugar!

Note: Do NOT add potassium sorbate to the wine at any stage if you are trying to make a pét-nat. Potassium sorbate will inhibit the yeast from fermenting through any stage of this process.

Familiarizing Yourself with Pét-Nats

Like with any wine style, it is ideal to have a sensory library of what quality pét-nats taste like using examples from the commercial market. The practice of tasting multiple examples of a specific wine style creates a benchmark library in the mind of the winemaker, which aids in making processing decisions in relation to an end-goal for the final product. It also helps define “quality” for that wine style.

While I have not embarked on an exploration to understand pét-nat quality, the following wines have been suggested in the above-mentioned articles or from individuals that have enjoyed pét-nats in today’s market. I highly suggest that any winemaker aiming to produce pét-nats, obtain various examples to evaluate 1) their individual preference of the product, 2) the potential consumer preference of the product, and 3) the quality parameters that the winemaker will aim for during production of a pét-nat style wine.

- Pétillant Naturel Malvasia Bianca (Suisun Valley) by Onward Wines

- Vin du Bugey-Cerdon “La Cueille” (A Kermit Lynch selection)

- “Nouveau-Nez” by La Grange Tiphaine (From the Loire)

- Several Suggestions Listed In This Article

References

Amerine, M.A., H.W. Berg, and W.V. Cruess. 1972. Technology of Wine Making, Third Edition. The AVI Publishing Company: Westport, Connecticut.

Granes, Daniel. 2015. Personal Discussion.

Guyard, Paul. 2015. Personal Discussion.

Jones, Michael. 2015. Personal Discussion.

Robinson, J. and J. Harding. 2006. The Oxford Companion to Wine. ISBN: 978-0198609902

Robinson, J., J. Harding, and J. Vouillamoz. 2014. Wine Grapes.

Wine and Spirit Education Trust (WSET). 2011. Wine and Spirits: Understanding Style and Quality. ISBN: 978-1 905819 15 7.

From “Emerging” to “Established:” Lessons and Suggestions to Develop an Emerging Wine Region

By: Denise M. Gardner

It’s hard to believe the Willamette Valley was nothing more than a handful of individuals with a passion for planting grapes in the unknown territory of Oregon 50 years ago. Today, the valley is a mosaic of hillside vineyards, farmland, and architecturally stunning wineries that decorate the land. A quick visit to McMinnville puts you right into the heart of Oregon’s wine country, and around every corner is a constant reminder that Oregon produces wine.

The Willamette Valley in Oregon is a great example of an emerging wine region that managed to “turn the tides” and be considered a serious wine-growing region for North America in such a short timeframe. Very few regions have managed such “overnight” success, although in talking with some of the founding producers, one can see that it was not an easy road.

Listed below are a series of memories, suggestions, and lessons that I recorded in talking to some of today’s premier wine producers in the Willamette Valley. While I learned various skills utilized on the production floor, I found myself captivated by the genuine way people in the wine industry documented their growth and current success. Such ideas are, perhaps, pivotal for emerging producers in Pennsylvania and the Mid-Atlantic regions that want to expand their reputation beyond that of the local radius and into the glasses of connoisseurs around the world.

One: Education is Key

One of the first things that several of the winemakers expressed as a necessity for emerging regions was education. The market professionals (i.e., sommeliers, chefs, distributors), consumers, and industry members all need to be addressed and educated in some way.

Some winemakers were quick to admit that the founding fathers of Oregon’s Willamette Valley did not know what they were doing all of the time. Many were coming from UC Davis’s viticulture and enology program, which focused on production in California. To grow Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, new growers knew they needed a cooler climate, which is what led them to Willamette. However, the change in climate brought its own challenges in disease pressure, figuring out which grapevine clones were best suited for Willamette’s terroir, and how to make wine that not only represented the region, but would be valued by consumers as well.

However, the one tie that kept everyone together was education. Growers and winemakers worked together extensively with one end goal: make good wine.

Nothing captures the motivation and awareness of improvement more than the 2012 documentary, “Oregon Wine: Grapes of Place,” which you can watch free on your personal computer: Oregon Wine: Grapes of Place OPB Special

Investment in education for the industry requires:

- Awareness of quality (what makes a good wine)

- Adhering to quality standards in the vineyard and in the winery. True, quality starts in the vineyard, but it ends in the winery. It is not good enough to adhere to good viticultural practices while putting the production of wine at a lower degree of importance.

- Bring in expertise and listen to their criticisms or suggestions. It is not easy to have someone comment on a wine that you love; I know. But, as a winemaker, it is your responsibility to learn and adapt. Understand the perspective of these people and work with them. It will progress quality farther than you can do alone.

- Value education and research; support it. Focused research answers questions that cannot be answered in the field, alone. Additionally, educational institutions should provide forums for conversation so that they can also learn from the industry.

The second component to this is education for the market and consumers: it is up to the wine industry to convince people they are making good wine. The first step in this is to make good wine. (You have to know the answer as to what makes good wine. See above.)

It was not surprising to me that one winemaker expressed that she still needs to work hard to sell wine. Despite the years of success that the Willamette industry has had, she indicated that it’s still a challenge to get the retail industry and consumers to adapt to new things. I think the lesson in this is: it will never be easy. As the winery, you will also have to work to push your product, even if the winery grows or gains worldwide attention. Preparing for that challenge can be a huge advantage as more consumers become aware of your product.

Two: Adapt to Growing Pains

One theme that was brought up routinely through my visit to Willamette was the fact that “in the beginning” of the industry, people sought out individuals that had expertise and they took the time to learn what they did not know. This is quite a humbling experience for individuals that may not have had the expertise in winemaking that they initially wanted. However, overcoming this hurdle and taking suggestions from all employees really helped progress the quality of Oregon wines forward.

Many wineries also invested in gaining outside experience: getting an education at UC Davis, consulting with individuals from Burgundy, or studying in Burgundy for a base education in making Pinot Noir, for example. Through this education and experience, they made changes to grape growing and winemaking practices within the region quickly.

How can wineries in the Mid-Atlantic improve their knowledge base or production techniques? Here’s a few suggestions:

- Hire employees that have expertise in the job. Do not assume you can teach anyone winemaking; it is not a recipe. All established regions eventually get to this point, which requires alterations to how the business aspect of the industry functions.

- Offer to help fund educational opportunities for your employees that may need to understand more about their job at hand. There are many programs available to do this, including the online Harrisburg Area Community College Viticulture and Enology Associates Degree program and local Extension programs.

- Encourage your production staff to participate in “harvest-hop” experiences. (See below)

- Organize and work together, and assume you will not always agree, but your agenda should be the same to be effective. If you watch the documentary above, extensive collaboration amongst the wineries was key to their early success. They swam and sank together. This got the industry political power and allowed them to be pioneers in enhancing their wines with the support of each other. One difference with the Oregon wine industry, however, is that they were varietally-focused on Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Pinot Gris from the onset of the industry’s development. While this may not be the case for a state like Pennsylvania, it does not mean that a few varieties could not be set aside to start improving upon collaboratively, while allowing room and growth for the various other products produced at individual wineries.

- Identify your niche as an industry and go after it. In the case of Oregon, this niche became recognition that they were not Burgundy Pinot Noir and they were not California Pinot Noir. They were somewhere in the middle, in their own niche market, and they gained local support as well as industry recognition. After hearing the recent lecture on wine typicity and terroir at last week’s Pennsylvania Quality Assurance (PQA) workshop, I realized that Willamette is still working to define Willamette Pinot Noir typicity. The fun thing about being in their current position is that in tasting a lot of wines, one can actually see a typicity emerge.

- Do not underestimate the ability to be creative. Pennsylvania routinely debates whether the industry can be taken seriously given the high production of sweet native varieties or various formula wines. However, I will note that even within an established, serious wine industry, one could find hints of creativity that had mass appeal. One of my favorite examples of this was Cugini Sparkling Grape Juice from Ponzi Vineyards. When made well, these products or other wine styles can help gain market share. However, quality is important in these products, too. They cannot be an outlet for flawed product with a hope of gaining reputation.

- Scaling Up Requires Adaptation. One challenge that is noticeable in any food production facility is the natural growing pains that come with increasing production volume: the product does not taste the same, parameters cannot be monitored the same was as they had in the past, techniques need to be altered, more staff is required for maintenance, etc. The greatest lesson I learned in Oregon is to prepare for these changes. Search out industry expertise that can help you avoid mistakes.

While not a growing pain, per se, but something I noticed: many of the productions stayed relatively small over time. Most fermentations were taking place in 2 – 3 ton fermenters, and there was a general preference to keep processing operations on the smaller side.

This allowed greater control over individual lots and flexibility in blending. Most productions maintained a portfolio of under 20 wines, but may have had hundreds of separate lots or barrels that were blended together to create a specific wine.

What was interesting to me was to taste the various vineyard-designated Pinot Noirs and find very dramatic differences (and preferences) for the wines. Blending is a valuable tool to winery, and having the knowledge of how to utilize this technique can be quite advantageous to an emerging region, especially one with a varying annual climate.

Three: Gain Experience

This is a big one, and it can seem daunting. However, all wine regions stem from humble beginnings. It is possible to gain experiences that help shape the quality of winemaking over time.

Harvest Hops: Harvest hopping involves jumping between the north and south hemispheres to participate in harvests (the southern hemisphere harvest in our winter months). Many people on the west coast utilize a few years of harvest hopping to gain experience and knowledge about various winemaking practices. This not only improves an individual’s education, but also provides confidence in the cellar. Not to mention that the enhanced awareness of wine quality from a different region improves the winemaker’s sensory perceptions.

Educate Children That May Take Over the Family Business: If your children have an interest in production, make them get an education in the area before signing them onto the family business. Most of the successful wineries require future generations to get some sort of education before joining the family business, and in the case of production, many require their kids to go oversees to get other production experiences that can help grow and change the family winery. This not only helps progress the business, but facilitates long-term planning.

Attend Educational Events: One large difference that I saw in Oregon compared to other wine regions is the value they place in educating themselves routinely. People make a large effort to attend research-based and trouble-shooting meetings on an annual basis. They recognize the value in education and that there is always something new to learn.

If you would like to be better aware of educational and research opportunities in Pennsylvania:

- Sign up for the “Penn State Extension V&E News” listserv

- Watch for Penn State Extension events here: http://extension.psu.edu/food/enology

- Attend the Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA) Annual Conference and PA Wine Marketing and Research Board (WMRB) Symposium.

- Participate on an industry board listed above.

- Watch for educational tidbits on Penn State Extension Enology’s Facebook page

- Continue using the “Wine & Grapes U.” blog site: psuwineandgrapes.wordpress.com

Train Your Palate: This is a key skill that is required to make high quality wines. It’s also a great skill to learn to enhance selling strategies to consumers. Knowing wines pertaining to various regions and producers expands your palate memory. From a winemaking perspective, it can help alter processing decisions to tailor the style of your wine. From a retail perspective, it can help more formally communicate with consumers and make more wine suggestions (from your winery) that is tailored to their preferences.

Grapes… Wine… and Bar-B-Q?! A Summary of the American Society of Enology and Viticulture (ASEV) & ASEV-Eastern Section Conferences: PART 1

By: Denise Gardner

This year, the national ASEV and ASEV-Eastern Section hosted joint conferences in Austin, Texas. There, researchers, students, and industry members met to discuss current research findings in academia and industry, explore the Texas Hill Country wine industry, and award prominent members of the grape and wine community.

This post, PART 1, will feature some highlights from Texas Hill Country and the presence of Penn State at the conferences. Next week, in PART 2, I’ll summarize a few of the enology talks that I attended and introduce these emerging concepts to the Pennsylvania wine community!

Texas Hill Country

The wine industry in Texas was fun to explore, and sometimes I couldn’t help but catch myself saying, “Everything is bigger in Texas.” ASEV hosted a one-day industry tour in the Texas Hill Country, which featured 4 vineyards and wineries: Flat Creek Estates, Becker Vineyards, Salt Lick Cellars, and Driftwood Estate Winery. Each winery had their own unique way of incorporating the pride of Texas into their production while retaining the prestige associated with wine. Vineyards loomed over various terrains and I was amazed at how early harvest occurs: for some, it starts as soon as July and ends by August!

At Flat Creek, we learned about the prominence of disease pressure in a constant hot and humid climate; a reality that many wine regions face on an annual basis. Flat Creek was currently exploring the use of ozone for pest management in the vineyard. Additionally, they were actively working with local universities on research projects associated with several vineyard pests and diseases, including Pierce’s disease. Several vineyard managers commented on the difficulty of getting vines into a dormant season because of the regular warm temperatures (the area does not have the classic diurnal shift between nighttime and daytime temperatures).

After a brief and sudden down pour, the out-of-towners had the opportunity to witness a Texas thunder storm, which left behind about 3 inches of water on top of the soil for a few hours. The kind folks at Becker Vineyards explained to us how important this annual rainfall is, as previous years have left the area in serious drought conditions. Within a few minutes, the bright Texas-blue skies were opening way again and drying off the vineyards. It was also at Becker that I caught a peek of one of the Texan wine awards!

It’s not surprising to me how Salt Lick Cellars brings people into their tasting room. Their famous Salt Lick Bar-B-Q restaurant brings in about 4,000 customers on weekends… and the tasting room is right next door! Talk about great marketing! Visitors have an opportunity to enjoy some of the most renowned Texan bar-b-q and quench their thirst for great Texan wines all in one stop. Bonus: the entire bar-b-q restaurant is surrounded by vineyards. Double bonus: the bar-b-q was delicious. A must-see (and taste) if you head down to Austin in the near future! (I suppose I’m still a foodie at heart.)

Finally, no wine industry is complete without that winery that captures the breathtaking views of their wine country. Driftwood Estate Winery captured this and did not disappoint as visitors were able to walk along the cliffs and look over onto the surrounding country-side.

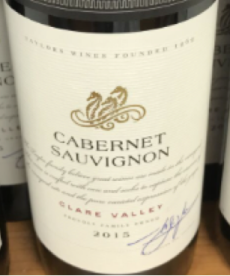

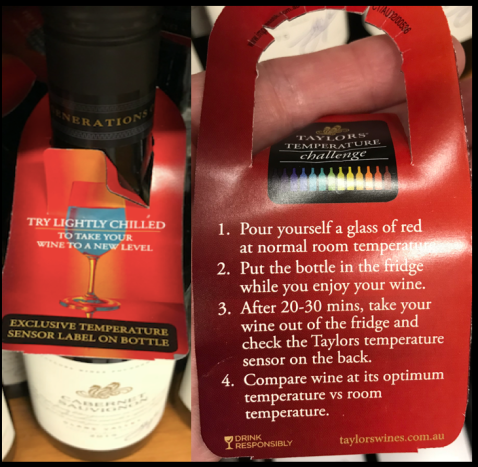

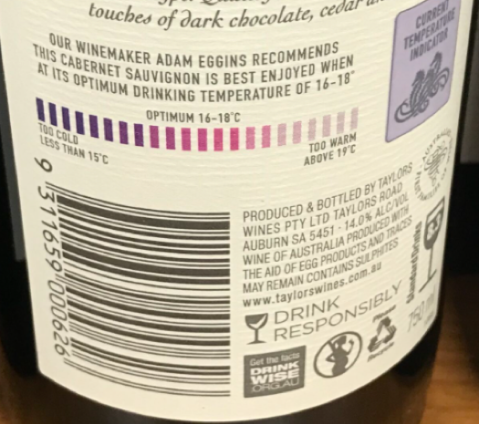

For me, it is always interesting to see what emerging wine industries are doing to promote their wines and how local consumers interact with the wineries, especially as the Pennsylvania Winery Association embarks on a new marketing campaign for Pennsylvania wines. The fascinating thing about Texas wines was the loyalty and pride found within consumers. In general, Texas is known as a high wine-consuming state. However, local consumers associate with brand loyalty to many Texas wines, and the local wines have a steady hand in the consumption numbers. Austin [city] restaurants, of all styles and price point, featured local wines. Finally, the hospitality associated with the wineries we visited was clearly genuine and I couldn’t help but notice how accommodating each winery had been during our trip. Many wineries chilled the reds slightly as ambient temperatures were too high to serve reds at “room temperature.” And many offered chilled water or Gatorade to winery visitors to account for that hot Texas weather! I also found a pack of “Go Texan” marketing material at the ASEV conference, which all attendees could take, and appreciated the support for the local wine industry. But how about those wines?

While some varieties were new to me, I was refreshingly reminded of how everyone loves a good rosé and of the multitude of wineries making nice Syrah’s. You can’t forget the multitude of Tempranillo’s that are sure to please red wine drinkers… and bar-b-q lovers. Reds retained pleasant jammy flavors and were smooth on the palate. I had a few Viognier’s that surprised me with their acid retention and tropical nuances. Like many other less-known wine regions, the wines I tasted in Texas had their own unique identity. This experience highlighted the contribution of terroir and its expression in the bottle.

Penn State at ASEV/ASEV-Eastern

This was one of the first years that Penn State had a strong presence at the ASEV national meeting. Several students attended the meeting with Michela Centinari (Assistant Professor of Viticulture) and myself (Extension Enologist). Gal Kreitman, current Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Food Science in Dr. Ryan Elias’s food chemistry lab, gave a well-attended enology talk discussing his research on how metal chelators may inhibit wine oxidation. Additionally, Gal was a scholarship recipient from both the ASEV and ASEV-Eastern organizations.

The Penn State group in Austin. From left: Gal, Jared, Michela, Laura, Charlene, Denise, and Marlena

I’d like to take a brief moment to recognize the importance of industry support for ASEV-Eastern scholarships. One of the primary missions associated with ASEV-Eastern is to provide financial support to graduate students exploring grape and wine research of importance to the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest wine regions (Pennsylvania included). This is especially important as federal financial support for grape and wine research seems to be declining. ASEV-Eastern cannot award these annual scholarships without financial contribution and support from the wine industries they represent. For more information on the ASEV-Eastern organization, present and past scholarship recipients, or how you can contribute to the ASEV-Eastern scholarship fund, please visit the website or donation page here. Additionally, you can now follow ASEV-Eastern on Facebook and view the various activities they are doing to support viticulture and enology research throughout wine regions east of the Rocky Mountains!

Charlene Van Buiten (Ph.D. candidate), Marlena Sheridan (Ph.D. candidate) and Jared Smith (M.S.), also a part of Dr. Ryan Elias’s food chemistry research lab, gave poster presentations on their current projects associated with wine. Charlene’s research highlight the use of the fining agent, PVPP, and its impact on the aroma and flavor of aromatic white wines when applied at various steps in production. Marlena has been studying the role of acetaldehyde, an impact aroma compound associated with oxidation, and its ability to stabilize red wine color. Jared’s research was recently discussed at the 2014 PA Wine Marketing and Research Board (WMRB) Symposium. He has been investigating the potential of native variety (e.g. Concord, Niagara) flavor carry-over into hybrid and V. vinifera wines during wine production.

Finally, Laura Homich, a recent B.S. graduate from the Chemistry Department at Penn State, also presented her research on the use of co-inoculation (simultaneous primary and malolactic fermentations) in high-acid red hybrid wines. Laura also presented this research at the 2014 PA WMRB Symposium, and will continue into an M.S. degree working with Dr. Ryan Elias and Dr. Michela Centinari. All of these students represented Penn State and the Pennsylvania wine industry quite professionally, and many attendees found their research of importance to many wine regions throughout the country.

I have to thank the continued support of the Pennsylvania wine industry through the financial contributions of the PA WMRB for many of these projects and the many wineries that have participated in these studies. Additionally, a special thank you goes to all of the faculty and staff members at Penn State that manage the research vineyards and contribute to the overall success of grape and wine research associated with the university. Without the continued collaborative efforts between the Pennsylvania wine industry and Penn State, the progression of grape and wine research in Pennsylvania would be quite limited.

Tune in next week for further updates regarding discussion topics at the ASEV and ASEV-Eastern Conferences!

Winter Injury and the Endless Mountains Region

By: Michela Centinari and Denise Gardner

This visit was a great opportunity to see several vineyards in the area and to engage in interesting discussions with local wine grape growers and vineyard managers. I was extremely impressed by the high quality of management being conducted in the vineyards. Jeff Zick, recently hired as vineyard manager at Nimble Hill Winery, is a great addition to the Endless Mountain region grower’s team.

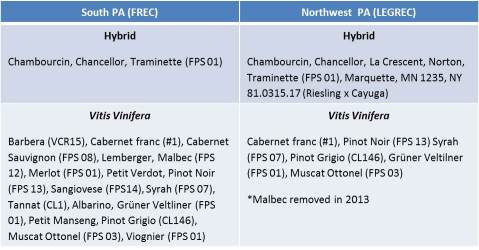

Most of the growers have both French-American hybrids, including cold-hardy varieties (Marquette, Frontenac gris, and Petite Pearl), and vinifera wine grape varieties, including Riesling, Gruner veltliner, Pinot grigio, and Pinot noir.

I also had a chance to evaluate the extent of winter cold injury the grapevines in this region experienced. As expected, the hybrids did not show much or any cold damage symptoms. Varying levels of cold damage were observed in the vinifera varieties. The growers pointed out sections of their vineyards, likely in poorly drained areas, where winter damage was extensive (i.e. near 100% bud mortality). However, other sections of the same vineyard experienced much less cold damage.

Vascular system damage was observed when sectioning canes with alive, but poorly growing shoots.

Unfortunately, those shoots will start to collapse during the summer.

Likely most of the vines have alive and healthy shoots developing on the scion side of the graft union area, which will need to be used to retrain new trunks.

If your vines experienced winter cold injury you can find useful information on how to deal with injured vines in the last issue of Viticulture Notes edited by Tony Wolf. http://www.arec.vaes.vt.edu/alson-h-smith/grapes/viticulture/extension/growers/current_VN_newsletter.pdf

In the winery, we talked about everything from the addition of bentonite during wine production, the use of temperature control during production of aromatic white wines, and defects associated with wine.

It is important to remember that the use of bentonite is related to the protein stability of wines. Adding a “standard addition” of bentonite to your wines does not guarantee protein stability in each wine produced. Additionally, some wines may not require a protein addition. For those wines that do not have protein instability issues, the addition of bentonite can contribute to some aromatic and flavor losses. I was impressed that Kevin, the winemaker at Nimble Hill Vineyard and Winery, has been keeping an accurate record of protein stability and total bentonite additions for each wine produced. This practice should be implemented at every winery if it is not done so already. For more information on protein stability and a brief protocol on protein stability testing, please refer to this document by Bruce Zoecklein.

There was a lot of discussion on aromatic white wine development, and the discussion was led through a tasting of several wines produced in Pennsylvania and throughout the world (benchmark producers). Aromatic white varieties like Riesling, Gewurztraminer, Vidal Blanc and delicate white varieties like Gruner Veltliner, Pinot Gris/Grigio, and unoaked Chardonnay should be refreshing with a bright acidity and fresh, fruity, floral aromas and flavors.

To retain these delicate aromas, it is recommended that wineries

- use temperature control during fermentation.

- limit the wine’s contact with oxygen to avoid oxidation and development of oxidative aromas.

- rack wines off the gross lees quickly after fermentation

- stabilize with sulfur dioxide additions (in temperature control tanks) soon after primary fermentation (if no MLF will occur).

When the tanks are not temperature controlled, warmer ambient temperatures can blow off the aroma and flavor compounds associated with these varieties, in addition to causing stability issues that may lead to the development of off-flavors. For some production addition options during aromatic white wine development, please review this document by Enartis Vinquiry.

Visiting the Endless Mountains region is always a pleasure. The region is quite picturesque, and if you haven’t had the opportunity to visit the region and taste their wines, I strongly recommend it.

Blind Tasting at the Lehigh Valley Wine Trail Meeting

Every year, the Extension Enology program tries to organize 5 “regional” wine meetings throughout Pennsylvania. These regional meetings usually occur in Central, Northwest, Northeast, Southeast, and Southwestern, Pennsylvania. Future Regional Visits can be found on the “Wine Industry Events” tab on this blog, or through the “Upcoming Events” heading on the homepage of the Penn State Extension Enology website.

Additionally, a few of the Pennsylvania wine trails also reach out Penn State Extension Enology for educational opportunities that include specific wine trails. The Lehigh Valley Wine Trail has been actively engaged with the Extension Enology program for a few years, and this year they developed a tasting exercise for their wine trail members.

Denise Gardner, Extension Enologist, worked with the Lehigh Valley Wine Trail to set up a blind tasting event which contained wines from all of the associated wine trail wineries. Each winery submitted a red and white wine of their choice, which was blinded with a brown paper bag (to cover the labels) and identified with a numeric three-digit code. Wines were then poured, individually, to each attending wine trail member. In total, 15 people tasted each wine submitted.

Each taster was given an evaluation sheet to analyze the wine for potential wine defects, the commercial acceptability of the wine as a whole, and completed with a subjective evaluation as to whether or not the taster enjoyed the wine. As we all know, wines can be of commercial quality but an individual’s taste preference may not prefer that wine, or vise versa.

Denise is currently in the process of compiling all of the data, and will provide a summary of each wine’s results to the appropriate winery.

What’s the benefit of educational programs like this?

- Blind tasting is a humbling experience. Winemakers often learn that they cannot recognize their own wines in a blind tasting line up. Imagine the unnerving experience!

- Tasting wines blind forces individuals to evaluate wines from a much different perspective. Not knowing a particular variety, focusing on particular attributes, and having little background on the wine can alter one’s sensory experience.

- Helps winemakers understand commercial acceptability. Denise struggled with a good definition for this term! Commercial quality wines are not wines that can be sold; as we all know almost any wine of any quality level can probably be sold to an unknowing consumer. However, looking at the wine from the perspective of “is this a quality wine?” is a subjective challenge that requires years of tasting, experience, and knowledge of benchmark quality wines throughout the world.

- Empowers team members to improve wine quality. The results of this exercise are focused on making wines better in a way that does not publicly harm any one producer. These exercises push the bar of making consistent quality wines, and the whole wine trail and/or region benefits from this adjustment. As the old saying goes, “Your wines are only as good as your neighbor’s.”