2019 PA Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium: Presentation Summaries

On March 5, 2019, Penn State researchers and Extension personnel presented research findings and provided five-minute overviews of upcoming studies at the 2019 Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium, held in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Winery Association Annual Conference.

In this post, we have included short summaries of what each presenter discussed during their session along with a PDF/access to their presentation.

Research presentations

Under-vine cover crops: Can they mitigate vine vigor and control weeds while maintaining vine productivity?

Presented by Michela Centinari, Assistant Professor of Viticulture, Suzanne Fleishman, Ph.D. Candidate, and Kathy Kelley, Professor of Horticultural Marketing and Business Management

Michela, Suzanne, and Kathy discussed research conducted at Penn State related to the use of under-vine cover crops as a management practice alternative to herbicide or soil cultivation. Michela reviewed potential benefits of under-vine cover crops, such as reduction of excessive vegetative growth, weed suppression, and reduced soil erosion. She showed how the selection of cover crop species depends on the production goals of a vineyard, climate, vine age, and rootstock. Suzanne presented results from her research project. She is investigating above- and belowground effects of competition between a red fescue cover crop and Noiret grapevines, comparing responses between vines grafted to 101-14 Mgt vs Riparia rootstocks. Surveys will be administered to Pennsylvania grape growers and wine consumers in the Mid-Atlantic region. Growers will be asked to respond to questions about interest in using cover crops and benefits that could encourage their use. The consumer survey will focus on learning whether cover crops use would impact their purchasing decision and if they would be willing to pay a price premium for a bottle of wine to offset additional production costs.

Impact of two frost avoidance strategies that delay budburst on grape productivity, chemical and sensory wine quality.

Presented by Michela Centinari, Assistant professor of Viticulture

Crop losses and delays in fruit ripening caused by spring freeze damage represent an enormous challenge for wine grape producers around the world. This multi-year study aims to compare the effectiveness of two frost avoidance strategy (application of a food grade vegetable oil-based adjuvant and delayed winter pruning) on delaying the onset of budburst, thus reducing the risk of spring freeze damage. Our objectives are to: i) evaluate if the delay in budburst impacts grape production and fruit maturity at harvest, as well as chemical and sensory wine properties; ii) elucidate the mechanism of action of the vegetable oil-based adjuvant through an examination of bud respiration and potential phytotoxic effects; and iii) assess the impact of the two frost avoidance strategies on carbohydrate reserve storage and bud freeze tolerance during the dormant season.

Toward the development of a varietal plan for Pennsylvania wine grape growers.

Presented by Claudia Schmidt, Assistant Professor of Agricultural Economics, and Michela Centinari, Assistant Professor of Viticulture

Claudia Schmidt is a new Assistant Professor of Agricultural Economics with an extension appointment at Penn State. Claudia used the opportunity of the symposium to introduce herself to the industry. In her presentation, she first gave an overview on what and where Pennsylvanians buy their wines and spirits. She then talked about the research needed to develop a varietal plan for the Pennsylvania grape and wine industry to match existing and future grape production and variety suitability with anticipated consumer demand. The immediate next steps on her research agenda are to develop a baseline survey of grape production in Pennsylvania and, in collaboration with Michela Centinari, region specific cost of production of grapes.

Survey for grapevine leafroll viruses in Pennsylvania: How common is it, and how is it effecting production and quality?

Presented by Bryan Hed, Research Technologist

This is a continuing project funded by the PA Wine Marketing and Research Board, that has focused on the determination of the incidence of grapevine leafroll associated virus 1 and 3 (the two most economically important and widely distributed of the leafroll viruses) in commercial vineyard blocks of Cabernet franc, Pinot noir, Chardonnay, Riesling, and Chambourcin, across the Commonwealth. Over two years, the survey has shown that grapevine leafroll associated viruses 1 and/or 3, were present in about a third of the vineyard blocks examined. Infection of grapevines by grapevine leafroll-associated viruses can have serious consequences on yield, vigor, cold hardiness, and most notably fruit/wine quality. Bryan also discussed a second phase of the project, anticipated to continue for at least another two years within 6 vineyard blocks of Cabernet franc, identified in the survey. In these vineyards, we plan to plot the spread of these viruses, examine and report their effects on grapevine vegetative growth, yield, and fruit chemistry, and characterize the influence of inter- and intra-seasonal weather conditions on virus-infected grapevine performance.

Integrating the new pest, spotted lanternfly, to your grape pest management program.

Presented by Heather Leach, Extension Associate

Spotted lanternfly (SLF) is a new invasive planthopper in the Northeast U.S. that threatens grape production. Heather covered the basic biology, identification, and current distribution of SLF. She also presented on the economic impact of SLF in the grape industry and ways to manage SLF in your vineyard. SLF can feed heavily on vines causing sap depletion in the fall which has resulted in death of vines, or failure of vines to set fruit in the following year. While biological controls such as pathogens and natural enemies along with trapping and behaviorally based methods are being researched, our current management strategy relies on using insecticides sprayed in the vineyard. Heather showed results from the 2018 insecticide trials conducted against SLF, with efficacy from several products including bifenthrin, dinotefuran, thiamethoxam, carbaryl, and zeta-cypermethrin. You can read more about the results from this trial here: https://extension.psu.edu/updated-insecticide-recommendations-for-spotted-lanternfly-on-grape

Five-minute research project overviews

Impact of spotted lanternfly on Pennsylvania wine quality.

Presented by Molly Kelly, Extension Enologist

The Spotted Lanternfly (SLF) presents a severe problem both due to direct damage to grapevines as well as their potential to impact wine quality. Insects are known to produce or sequester toxic alkaloid compounds. The objectives of this study include characterizing the chemical compounds in SLF and production of wines with varying degrees of SLF infestation. We can then provide winegrowers with recommendations for production of wine from infested fruit. Toxicity studies will be conducted to determine the levels of toxic compounds in finished wine, if any, using a mouse bioassay.

Exploring the microbial populations and wild yeast diversity in a Chambourcin wine model system.

Presented by Chun Tang Feng, M.S. Candidate, and Josephine Wee, Assistant Professor of Food Science

In Dr. Josephine Wee’s lab, we are interested in the microbial population and diversity associated with winemaking. When it comes to wine fermentation, not only are commercial yeasts involved in this process, but also many indigenous yeasts. Our research goal is to isolate the wild yeasts and assess their feasibility of wine fermentation. We are expecting to explore the unique yeast strains from local PA which are able to make a positive impact on wine flavor.

Rotundone as a potential impact compound for Pennsylvania wines

Presented by Jessica Gaby, Post-Doctoral Scholar and John Hayes, Associate Professor of Food Science

This study will examine Pennsylvania consumers’ perceptions of rotundone with the goal of determining whether a rotundone-heavy wine would do well on the local market. This will be examined from several different perspectives, including sensory testing of rotundone olfactory thresholds, liking and rejection thresholds for rotundone in red wine, and PA consumer focus groups. The ultimate aim of the study is to determine the ideal concentration of rotundone in a locally-produced wine that would appeal to PA consumers.

Defining regional typicity of Grüner Veltliner wines

Presented by Stephanie Keller, M.S. Candidate, Michela Centinari, Assistant Professor of Viticulture, and Kathy Kelley,

Grüner Veltliner(GV) is a relatively new grape variety to Pennsylvania, and while climatic conditions are favorable to its growth, the Pennsylvania wine industry is still becoming familiar with the varietal characteristics of GV grown and produced throughout the state. This study focuses on defining typicity of Pennsylvania-grown GV wines. Typicity is described as the perceived representativeness of a wine produced from a designated area, and defining typicity can improve wine marketing strategies. This study uses multiple experimental sites across the state to create wines from a standardized vinification method. The wines will be analyzed using both instrumental and human sensory methods.Surveys will be administered to Pennsylvania grape growers and white wine consumers in the Mid-Atlantic region. Growers will be asked their interest in growing GV and what perceived and real barriers may impact their decision to grow the variety. The consumer survey will focus on understating how to introduce them to a wine varietal they may be less aware of and what promotional methods may encourage them to purchase the wine.

Boosting polyfunctional thiols and other aroma compounds in white hybrid wines through foliar nitrogen and sulfur application?

Presented by Ryan Elias, Associate Professor of Food Science, Helene Hopfer, Assistant Professor of Food Science, Molly Kelly, Extension Enologist, and Michela Centinari, Assistant Professor of Viticulture

The quality of aromatic white wines is heavily influenced by the presence of low molecular weight, volatile compounds that often have exceedingly low aroma threshold values. Polyfunctional varietal thiols are an important category of these compounds. This project aims to provide research-based viticultural practices that could lead to increases in beneficial varietal thiols in white hybrid grapes. The expected increase in overall wine quality will be validated both by measuring the concentrations of these desirable compounds (i.e., thiols) in finished wines using instrumental analysis and by human sensory evaluation, thus providing a link between the viticultural practice of foliar spraying and the improvement of overall wine quality.

Harvesting the Knowledge Accumulated at Penn State on Grapes and Wine

By: Denise M. Gardner

Early in 2016, I was asked to create a “behind the scenes” event in late October to feature our research winemaking program and share this with alumni to introduce them to some of the things that Penn State offers in the fields of viticulture and enology. This was, by far, one of the most interesting events I have organized during my time with Penn State, and it ended up being a very rewarding experience, personally, to see the pride and talent that contributed to make the event a success.

The challenge: teach a group of adults about wine production… most of whom have probably very little knowledge about or experience in actual wine production.

As many of us know, making wine is not really the romantic ideal that is often portrayed and associated with the wine industry. We all know that we aren’t overlooking our vineyards with a glass of wine in hand 24-7.

It’s hard work. It’s dedication. And it’s farming.

When I introduced this event idea to the Extension Enology Advisory Committee – a group composed of 13 volunteers from Pennsylvania’s wine industry and several representatives from various academic communities – they all jumped on the idea of showcasing the Penn State Extension Enology presence and the impact it has had on the local industry in addition to Penn State’s research programs.

Starting in April 2016, I went to work on developing a short [film] script to organize and develop a small video that highlighted our research initiatives and student involvement around winemaking at Penn State. The hope was that this video would feature how students, faculty, and staff are getting involved with industry members via Penn State Extension’s programs while also explaining how wine is generally produced.

With this video, I ended up interviewing two faculty members from our research team, Dr. Michela Centinari from the Dept. of Plant Sciences and Dr. Ryan Elias from the Dept. of Food Science. We collected their perspectives and opinions on various activities that they have been involved in and related it back to the growth and development associated with Penn State offering educational and research experiences in viticulture, enology, and wine marketing.

Figure 1: Filming Day! Dr. Ryan Elias, Dr. Michela Centinari, and Denise Gardner get interviewed and video taped for a small presentation on winemaking at Penn State. Filming completed by media guru, Jon Cofer. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Luckily, one of the media specialists within the College of Agricultural Sciences, Jon Cofer, had a collection of footage that we had shot during wine processing days just in case we ever needed video footage for anything. As luck would have it, we did need the media footage! Jon sifted through hours of film to find the best footage, which we then tied back into the explanation on how research wines are generally processed at Penn State.

During our travels around the state, whether it was to check in on research trials or visit with industry members during Regional Winery Visits, Michela, a group of dedicated graduate students, and I collected video footage in commercial vineyards in an attempt to highlight what goes on during the growing season. And finally, I met with some recent graduates that experienced educational opportunities through Penn State and Extension, and who both work in Pennsylvania’s wine industry today. I have to admit, one of the most awarding experiences in being Penn State’s Extension Enologist is that I have watched several “students” graduate and find full-time job placement within our state’s wine industry. It is an absolute joy to see these young adults exceed in a growing industry.

The result of this event couldn’t have been better received. Instead of making wine with a group of non-winemakers, we set up three educational stations to teach about:

- wine grape properties and vineyard management by highlighting how to conduct a berry sensory analysis, explaining berry physiological differences, and teaching how to read a refractometer.

- the chemistry behind fermentation and sensory training associated with wine tasting through analytical demonstrations and “aroma guessing” with aroma standards.

- and evaluating the end result (finished wine!) of some of our best research wines and commercial winery collaborators.

Figure 2: Graduate students, Maria and Drew, get ready to teach attendees about wine grape properties. Maria and Drew are members of Dr. Michela Centinari’s research lab. Photo by: Tom Dimick

Figure 3: Jared Smith (Dept. of Food Science Teaching Lab Support Specialist and previous graduate supported by the Crouch Endowment) explains how winemakers monitor fermentation and the use of temperature-controlled fermentation tanks. Photo by: Tom Dimick

Figure 4: Graduate student, Laurel, tests attendees on their ability to smell and aroma and guess what it is. Laurel works within Dr. Ryan Elias’s lab. Photo by: Tom Dimick

Figure 5: Denise Gardner pours some of the commercial wines for attendees and explains how to pair them with locally produced cheeses. Photo by: Tom Dimick

Figure 6: Dr. Michela Centinari pours and explains the research wine trials. Attendees loved this portion of the program and were truly impressed with the quality wines produced by our research team! Photo by: Tom Dimick

The educational portion of this program was a big success. Attendees learned about native and wine grape varieties grown in Pennsylvania, and how those grapes compare to table grapes that people see in grocery stores. At the fermentation booth, participants learned how to measure Brix to determine potential alcohol and how a temperature-controlled stainless steel tank can be useful in wine production. Additionally, our graduate students put guests’ nose-sniffing skills to the greatest test in seeing if they could guess various wine aromas without peaking at the answers! It was enlightening to see our students teach the importance of these skills to develop a career in the wine industry.

The Penn State research wines that are made at University Park were also a big hit. Explaining the purpose of research wines can be a slight challenge, as most of our wines are never finished. This means that in order to emphasize a vineyard or winemaking treatment, fining, stabilizing, and finishing treatments (like oak aging) are kept to an absolute minimum or completely avoided. In many cases, bottled wines will never see any oak or fining other than getting racked off of their lees.

Our primary display was on the Noiret wines, which was a project funded by the PA Wine Marketing and Research Board to determine if vineyard management treatments affected the concentration and perception of rotundone, the primary aroma compound associated with the Noiret variety that exudes a black pepper aroma. The rosé wine, also made from Noiret, was an excellent contrast to the red wines produced from the same variety. Pairing the wines with various cheeses produced by Berkey Creamery was an excellent way to also talk about wine styles produced in Pennsylvania and the importance of food and wine pairing with many of the local wines.

If you are interested in tasting many of our wine trials, please join us at the annual PA Wine Marketing and Research Board Symposium. The 2017 Symposium will be held in University Park on March 29th! (More details on this conference will be released soon!)

But what happened to that video?! If you are still interested in evaluating our winemaking program, curious about what we have been up to for the past few years, please feel free to enjoy our short 12 minute video that highlights a small portion of our efforts to work with industry and participate in viticulture and enology research. While the program is young, we have truly been fortunate to work with some pretty amazing people: commercial growers and producers that are interested in research, students developing expertise, and other academic colleagues that have been willing to collaborate with us as we build our programs.

We truly hope that you have seen or experienced some of the benefits of our programs, but if you would like to know more about what we do, please do not hesitate to contact us! Our email addresses are readily available and we also try to document our regular activities on Facebook. We honestly couldn’t do it without the support of people like YOU!

Enjoy the video! We think it is fairly entertaining, a lot of work went into it, and it showcases a small fraction of the things we are trying to do at Penn State to help progress and educate the local wine industry:

(If you do not have a dropbox account, simply hit “No Thanks” when the pop up window is displayed. You can also do this if you would like to avoid logging into dropbox.)

Tasting Chambourcin: Part I

By: Denise M. Gardner

Note: Sensory descriptions of wines produced by the grape variety, Chambourcin, are based on individual observations, tastings, and a collection of notes obtained through various Chambourcin tastings including many different individuals.

At the Central Pennsylvania regional winery meeting held at Brookmere Winery, attendees and I had the opportunity to taste through a series of Pennsylvania-grown and produced Chambourcin wines. This was actually one of the first all-Chambourcin wine flights that I have been able to taste, and I was quite encouraged by what I was tasting in the glass. Paula Vigna, writer for The Wine Classroom via Penn Live, has since written an article on the tasting titled, “Chambourcin’s ceiling: Maybe higher than originally thought.”

Chambourcin: A Description

Chambourcin is a French-American hybrid wine grape variety that was bred by crossing Seyve-Villard 12-417 (Seibel 6468 x Subéreux) with Chancellor*, commercialized in 1963 (Robinson et al. 2012). Despite Chambourcin’s vigor and relative tolerance to disease pressure in humid climates, anecdotally the wine does often appear preferred by many Vitis vinifera winemakers.

As a wine, Chambourcin’s strength is its vibrant red color and supple, soft mouthfeel due it is relatively lack of course tannin on the palate. These features often make it a valuable red wine blending possibility, especially considering the relative consistency of obtaining Chambourcin fruit every vintage. However, the smoothness of the wine often is a frustration by many eastern winemakers looking for more depth and [tannin-related] mouthfeel in their red wines. When coupled with Chambourcin’s notorious ability to retain acidity, often above 7 g/L of tartaric acid (depending on where and how it is grown), the lack of perceived tannin can make the wine taste relatively thin and acidic.

The acidity associated with the Chambourcin grape variety often appears retained when grown in cooler climates. For example, in Pennsylvania, Chambourcin produced in North East, PA (Erie County) often has relatively higher TAs compared to Chambourcin grown in southeastern, PA (e.g., Berks County). From a grape growing perspective, all winemakers should expect this phenomenon. However, Chambourcin can retain a higher acidity even when grown in the warmer southern parts of Pennsylvania. Based on observation, the variety seems to maintain its acidity when it is not thoroughly crop thinned. As Chambourcin is an incredibly vigorous variety, and as you will see from the tasting, producers hoping to drop the acidity often crop thin grape clusters while on the vine.

When looking at the tannic composition of Chambourcin, it is likely that much of the tannin content associated with Chambourcin is lost during primary fermentation. Dr. Gavin Sacks at Cornell University is studying this situation associated with many hybrid wine fermentations. As Dr. Sacks discussed at the 2016 Pennsylvania Wine Marketing & Research Board (PA WMRB) Symposium in March, tannins come from 3 different components of the grape: the stems, the skin, and the grape seeds. During the fermentation process, anthocyanins (red pigments) and skin tannin is extracted quickly, usually before the product starts to ferment. Seed tannin is extracted more slowly, typically throughout primary fermentation and extended maceration processes. Dr. Sacks’ lab (Springer and Sacks, 2014) and previous research (Harbertson et al. 2008) have shown, grapes produced outside of the western U.S. generally have lower concentrations of tannin available in the grape. While available tannin in the grapes does not necessarily correlate with tannin concentrations in the finished wine, many eastern U.S. winemakers will add exogenous tannin pre-fermentation, during fermentation, and/or post-fermentation to help improve mouthfeel and potentially increase substrate availability for color stability reactions. However, even with exogenous tannin additions, Dr. Sacks has found that many of the tannins associated with hybrid fermentations end up lost during the fermentation process due to protein-tannin binding complexes that pull tannins out of the wine. The higher protein concentration associated with the hybrid grapes has been linked to disease resistance mechanisms that the varieties were originally bred for, and is more thoroughly explained in Dr. Anna Katharine Mansfield’s recent Wines & Vines article, “A Few Truths About Phenolics.”

Additionally, Chambourcin has been noted to have a relatively neutral red wine flavor, lacking a concentrated pop of fruit and using non-descript aromatic or flavor descriptors like: red cherries, red fruit, red berries, stemmy, herbal, or even millipedes. And yes, I have heard one or two consumers actually reference a millipede aroma when tasting Chambourcin.

Tasting Chambourcin Produced in PA

Figure 1: Flight of Chambourcin Wines tasted at the June 2016 Central PA Regional Wine Meeting, hosted by Brookmere Winery. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

The official flight (Figure 1) of Chambourcin wines that I had put together included:

- Galen Glen Winery 2014 Stone Cellar Chambourcin

- Penns Woods Winery 2014 Chambourcin Reserve

- Vynecrest Winery 2014 Chambourcin

- Pinnacle Ridge Winery 2013 Chambourcin Researve

- Allegro Winery 2012 Chambourcin

Additionally, Brookmere Winery, Armstrong Valley Winery, and Caret Cellars (Virginia) added Chambourcin wines to taste. The formal wine tasting turned out to be quite a unique experience.

I saw a few over-arching sensory themes within these wines:

- Reduced acidity: While I did not personally measure the pH and TA for these wines, the perception of acidity was not as obvious, overly perceptible, or offensive.

- Soft, supple mouthfeel: Even with a couple of the wines that were perceived as “more tannic,” these wines were soft and easy-drinking.

- Use of oak barrels: Many of the producers were opting for some production in actual oak barrels as opposed to using oak alternatives. Type of oak ranged from French, American, and Hungarian.

- Higher alcohols: Alcohol concentrations for these wines ranged from 13-14%, likely due to extended hang time in the vineyard, allowing for an increase in sugar accumulation.

- Two emerging aromatic profiles: A couple of the wines were very fruit-forward and fruitier than what is normally expected from Chambourcin. The other wines were less fruit-forward, however, they did retain a fair amount of red fruit aromatics in addition to the complex aroma nuances: earthiness, tobacco, toasted oak, vanilla, and tobacco. Many tasters commented on the general concentration of aromatic nuance associated with many of the wines we tasted.

In general, the relative depth, cleanness, and fruit expression of these wines was impressive. Perhaps this tasting clearly indicated that although many winemakers struggle with finding the “right fit” or style for their Chambourcin, the level of quality associated with the wine has definitely improved within the last 5 years. At the very least, the level of quality associated with this flight of wines was encouraging for hybrid red wine producers.

Additionally, Brookmere Winery provided a real treat from their cellar library: a 1998 Chambourcin produced by Brookmere Winery (Figure 2) when Don Chapman owned the winery. If you appreciate older wines, then this Chambourcin would truly impress you. Not only did it express the “old wine” honey-floral character loved by many wine enthusiasts, but the red fruit aromas and flavors were still boldly expressed in the wine. The color was intense and dynamically red, and there was a fine perception of firm tannins on the palate. Overall, the tasting of this wine gave me the perception that not only did this wine still have plenty of room to continue aging in the cellar, but that Chambourcin, as a wine varietal, had positive potential for aging for more than 10 years.

Given that most of this post is based on my own experiences, perceptions, and information gathered from growers and producers pertaining to Chambourcin, I would welcome any additional experiences with the variety (as a grape or as a wine) in the comments section.

While this post has documented Chambourcin as a grape variety and a small snap shot of sensory perceptions from a handful of producers in Pennsylvania, next week’s post will focus on production techniques to improve the quality Chambourcin red wines.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

For more information on upcoming regional meetings and the types of tastings to be held at those FREE events, please visit: http://extension.psu.edu/food/enology/events

- Northwestern PA (Erie County) – Individual Site Visits

- Southwestern PA (La Casa Narcisi Winery) – Talk on High Potassium Winemaking

- Southeastern PA (Vineyard at Grandview) on Thursday, July 28th – Berry Sensory Training hosted by Lallemand, with international wine consultant Dominique Deltei (Must register with Denise (dxg241@psu.edu) as space is limited to 15 people.)

Resources

Harbertson, J.F., R.E. Hodgins, L.N. Thurston, L.J. Schaffer, M.S. Reid, J.L. Landon, C.F. Ross, and D.O. Adams. 2008. Variability of tannin concentration in red wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 59:210-214.

Mansfield, A.K. January 2015. A few truths about phenolics. Wines & Vines.

Robinson, J., J. Harding, and J. Vouillamoz. 2012. “Chambourcin.” pg. 218-219. Wine Grapes. ISBN: 978-0-06-220636-7

Springer, L.F. and G.L. Sacks. 2014. Protein-precipitable tannin in wines from Vitis vinifera and interspecific hybrid grapes (Vitis ssp.): differences in concentration, extractability, and cell wall binding. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62(30):7515-7523.

*Authors Note: Since the publication of this article, a few growers and grape breeders have alluded to the improperly reported parentage of Chambourcin. While it is generally reported and cited as such, it is understood among some wine grape experts that Chancellor is not likely a parent to Chambourcin. For more information on determining parentage of given grape cultivars, please refer to: http://www.vivc.de and search the cultivar name of interest.

What is Enology?

By: Denise M. Gardner

By definition, (o)enology is the study of wine and winemaking (Robinson 2006). The field of enology differs from that of viticulture, the science of grape growing, although the two are often intertwined in academic departments across the United States.

An (o)enologist is one that practices the field of (o)enology, and often understands the scientific principles associated with winemaking, including desirable characteristics associated with the grape itself. Enologists tend to understand wine analysis and can make educated decisions during wine production based on the analytical description and, potentially, sensory description of a given wine. Many enologists do not actually have a degree in “enology” per se, although enology degree programs exist throughout the world. In fact, many industry enologists have a science degree in chemistry, microbiology, biology, food science or another related field.

I find myself often making the argument that an enologist is actually a food scientist that specializes in the production of wine. While it may appear less glamorous in words, many enologists that have studied in the U.S. have Bachelors of Science degrees from institutions in which “enology” is embedded within the food science department. While the art of crafting a quality wine is unique to the product, and can require years of adequate sensory training or experience, the equipment and production techniques associated with winemaking are also utilized in the commercial production of many food and beverage products.

Penn State Food Science undergraduate students learn pilot scale research winemaking techniques associated with commercial winemaking practices and enology. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

What does an (o)enologist do?

Being an enologist does not necessarily indicate that that individual is also the winemaker. In the book, “How to Launch Your Wine Career,” the authors (Thatch and D’Emilio 2009) explain the two arms associated with wine production in California: the winemaker and the enologist. For a head winemaker position, one typically has to work up the ladder from assistant winemaker, and may find themselves in several assistant winemaker positions prior to holding a head winemaker position. The enologist position develops through a different ladder within the winery: from a crush (or harvest) intern to a cellar worker to a lab assistant and finally a cellar master before reaching the enologist position. Note that this development may not always be the case in smaller, commercial wineries.

In larger wineries, many enologists focus on working within a winery’s lab. Their primary duties could range from conducting daily wine analysis and monitoring quality control parameters of all of the wines, to training additional employees (lab assistants, lab technicians, harvest interns) in running analysis, to assisting the winemaker with specific tasks (e.g., setting up blending trials, recording data on blending trials, field trials, or wine trials, and accomplishing cellar tasks). In smaller wineries, the enologist will tend to wear several hats, and may also be associated as the head winemaker for the establishment.

Understanding analytical techniques associated with the quality control of wine production is an essential component of being an enologist. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Is an enologist the same thing as a sommelier?

Enologists should not be confused with sommeliers, which the Oxford Companion to Wine defines as a “specialist wine waiter or wine steward.” Sommeliers are typically employed by restaurants, distributors, or other retail entities to advise consumers on wine purchases at a specific establishment. It is not uncommon for sommeliers to determine a wine list for a restaurant or to advertise food and wine pairings based on the restaurant’s menu and available wine selection.

Education in a sommelier certificate program focuses on introductory viticulture and winemaking knowledge; a broad overview of terms and basic production practices (i.e., how to make a white wine versus a red wine). Their focus will feature global wine producing regions (e.g., regions within France like Bordeaux, Burgundy, the Loire, etc.), wine styles and the characteristics associated within specific regionally (terroir-driven) produced wines. Written knowledge is supplemented with educational tastings, and most sommelier and sommelier-like programs have a unique tasting method that is taught and practiced by all pupils. Additionally, some sommelier programs feature education on the various types of spirits produced internationally and the sensory evaluation thereof. Sommeliers understand how to interpret wine regions and what to expect stylistically from a wine that is presented to them. Despite the depth of knowledge in these areas, sommelier training does not focus on actual production techniques. A sommelier is not trained in a wine processing facility, nor taught the scientific component to winemaking, and their approach to wine tasting often differs from those in production. I have often found that sommelier’s evaluation of a wine can supplement that of the winemaker in a positive way, and emphasizes how varied sensory perceptions of wine truly are based on one’s training and experience.

Wine sensory evaluation – an educational tasting session – hosted by a Wine and Spirits Education Trust class. Flights of wine are chosen to emphasize regional and stylistic characteristics that are specific to a given region. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

There are several organizations that train sommeliers. The most famous and prestigious organizations for sommelier credentials include the Court of Master Sommeliers and the Masters of Wine (MW) programs. Certification typically requires participants to pass several exams, written and oral (i.e., mock sommelier serving exams or blind wine tastings with adequate identification of each wine). The Masters of Wine program also includes a written research paper on a select wine topic.

There is also a number of regional and local sommelier training and certificate programs, or wine education courses, available to interested parties.

Is it important for a winery to hire an enologist?

For a smaller, commercial winery (<10,000 cases), having an on-site enologist is beneficial for a winery, especially if the enologist is trained to make wine, run and interpret lab analysis, and adequately taste wines. Essentially, their role takes can take the “guess work” out of winemaking. An enologist’s skill and expertise can completely transform a winery’s brand and quality, especially if that individual is employed to accomplish two production tasks: enologist (i.e., lab analysis) and winemaker. Additionally, a winemaker can also train to improve their skills in the lab to also act as the winery’s enologist.

How to become more affluent in enology?

In Pennsylvania, there are a number of ways that one can improve their knowledge in enology. First, it is best to identify what you want to do.

- Are you interest in making or producing wine on the production floor?

- Do you have an interest in science and lab analysis?

- Or are you looking into a broader knowledge for making wine and food pairings?

For the first two points, if you are looking to switch careers or already employed by the wine industry, but think you need a more in-depth background in the scientific principles associated with wine production and/or analysis, a good starting point is Harrisburg Area Community College’s (HACC) online viticulture and enology Associate’s Degree program: http://bit.ly/HACCVandE

Additionally, Penn State Extension offers several workshops, short courses, webinars, and educational events that are designed for the commercial wine industry: http://extension.psu.edu/food/enology

Penn State Extension Enologist, Denise M. Gardner, tastes wines with Wine Quality Improvement (WQI) Short Course attendees to diagnose wine defects/flaws within commercial wines. Photo by: Michael Black/Black Sun Photography.

Sometimes, it is beneficial to enroll in broader food production short courses to enhance one’s baseline knowledge. Such short courses include like:

- Fundamentals of Food Science

- Food Sanitation Short Course

- Food Microbiology Short Course

- Principles of Sensory Evaluation

- Wine Quality Improvement

Additionally, many other Extension programs feature wine- and grape growing-specific workshops tailored towards to the commercial wine industry.

How to broaden your wine knowledge

However, if you found yourself wanting a broader background in understanding wine regions, wine styles, and wine (in general), without getting into winemaking, then you may want to look into a wine education course that follows a sommelier curriculum. Several are featured in Pennsylvania, and offer a wide range of expertise levels:

- The International Sommelier Guild

- com

- Wine and Spirits Education Trust (WSET)

- The Wine School of Philadelphia

References

Robinson, J. 2006. The Oxford Companion to Wine. Oxford University Press, New York.

Thach, L. and B. D’Emilio. 2009. How to Launch Your Wine Career. The Wine Appreciation Guild, San Francisco.

From “Emerging” to “Established:” Lessons and Suggestions to Develop an Emerging Wine Region

By: Denise M. Gardner

It’s hard to believe the Willamette Valley was nothing more than a handful of individuals with a passion for planting grapes in the unknown territory of Oregon 50 years ago. Today, the valley is a mosaic of hillside vineyards, farmland, and architecturally stunning wineries that decorate the land. A quick visit to McMinnville puts you right into the heart of Oregon’s wine country, and around every corner is a constant reminder that Oregon produces wine.

The Willamette Valley in Oregon is a great example of an emerging wine region that managed to “turn the tides” and be considered a serious wine-growing region for North America in such a short timeframe. Very few regions have managed such “overnight” success, although in talking with some of the founding producers, one can see that it was not an easy road.

Listed below are a series of memories, suggestions, and lessons that I recorded in talking to some of today’s premier wine producers in the Willamette Valley. While I learned various skills utilized on the production floor, I found myself captivated by the genuine way people in the wine industry documented their growth and current success. Such ideas are, perhaps, pivotal for emerging producers in Pennsylvania and the Mid-Atlantic regions that want to expand their reputation beyond that of the local radius and into the glasses of connoisseurs around the world.

One: Education is Key

One of the first things that several of the winemakers expressed as a necessity for emerging regions was education. The market professionals (i.e., sommeliers, chefs, distributors), consumers, and industry members all need to be addressed and educated in some way.

Some winemakers were quick to admit that the founding fathers of Oregon’s Willamette Valley did not know what they were doing all of the time. Many were coming from UC Davis’s viticulture and enology program, which focused on production in California. To grow Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, new growers knew they needed a cooler climate, which is what led them to Willamette. However, the change in climate brought its own challenges in disease pressure, figuring out which grapevine clones were best suited for Willamette’s terroir, and how to make wine that not only represented the region, but would be valued by consumers as well.

However, the one tie that kept everyone together was education. Growers and winemakers worked together extensively with one end goal: make good wine.

Nothing captures the motivation and awareness of improvement more than the 2012 documentary, “Oregon Wine: Grapes of Place,” which you can watch free on your personal computer: Oregon Wine: Grapes of Place OPB Special

Investment in education for the industry requires:

- Awareness of quality (what makes a good wine)

- Adhering to quality standards in the vineyard and in the winery. True, quality starts in the vineyard, but it ends in the winery. It is not good enough to adhere to good viticultural practices while putting the production of wine at a lower degree of importance.

- Bring in expertise and listen to their criticisms or suggestions. It is not easy to have someone comment on a wine that you love; I know. But, as a winemaker, it is your responsibility to learn and adapt. Understand the perspective of these people and work with them. It will progress quality farther than you can do alone.

- Value education and research; support it. Focused research answers questions that cannot be answered in the field, alone. Additionally, educational institutions should provide forums for conversation so that they can also learn from the industry.

The second component to this is education for the market and consumers: it is up to the wine industry to convince people they are making good wine. The first step in this is to make good wine. (You have to know the answer as to what makes good wine. See above.)

It was not surprising to me that one winemaker expressed that she still needs to work hard to sell wine. Despite the years of success that the Willamette industry has had, she indicated that it’s still a challenge to get the retail industry and consumers to adapt to new things. I think the lesson in this is: it will never be easy. As the winery, you will also have to work to push your product, even if the winery grows or gains worldwide attention. Preparing for that challenge can be a huge advantage as more consumers become aware of your product.

Two: Adapt to Growing Pains

One theme that was brought up routinely through my visit to Willamette was the fact that “in the beginning” of the industry, people sought out individuals that had expertise and they took the time to learn what they did not know. This is quite a humbling experience for individuals that may not have had the expertise in winemaking that they initially wanted. However, overcoming this hurdle and taking suggestions from all employees really helped progress the quality of Oregon wines forward.

Many wineries also invested in gaining outside experience: getting an education at UC Davis, consulting with individuals from Burgundy, or studying in Burgundy for a base education in making Pinot Noir, for example. Through this education and experience, they made changes to grape growing and winemaking practices within the region quickly.

How can wineries in the Mid-Atlantic improve their knowledge base or production techniques? Here’s a few suggestions:

- Hire employees that have expertise in the job. Do not assume you can teach anyone winemaking; it is not a recipe. All established regions eventually get to this point, which requires alterations to how the business aspect of the industry functions.

- Offer to help fund educational opportunities for your employees that may need to understand more about their job at hand. There are many programs available to do this, including the online Harrisburg Area Community College Viticulture and Enology Associates Degree program and local Extension programs.

- Encourage your production staff to participate in “harvest-hop” experiences. (See below)

- Organize and work together, and assume you will not always agree, but your agenda should be the same to be effective. If you watch the documentary above, extensive collaboration amongst the wineries was key to their early success. They swam and sank together. This got the industry political power and allowed them to be pioneers in enhancing their wines with the support of each other. One difference with the Oregon wine industry, however, is that they were varietally-focused on Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Pinot Gris from the onset of the industry’s development. While this may not be the case for a state like Pennsylvania, it does not mean that a few varieties could not be set aside to start improving upon collaboratively, while allowing room and growth for the various other products produced at individual wineries.

- Identify your niche as an industry and go after it. In the case of Oregon, this niche became recognition that they were not Burgundy Pinot Noir and they were not California Pinot Noir. They were somewhere in the middle, in their own niche market, and they gained local support as well as industry recognition. After hearing the recent lecture on wine typicity and terroir at last week’s Pennsylvania Quality Assurance (PQA) workshop, I realized that Willamette is still working to define Willamette Pinot Noir typicity. The fun thing about being in their current position is that in tasting a lot of wines, one can actually see a typicity emerge.

- Do not underestimate the ability to be creative. Pennsylvania routinely debates whether the industry can be taken seriously given the high production of sweet native varieties or various formula wines. However, I will note that even within an established, serious wine industry, one could find hints of creativity that had mass appeal. One of my favorite examples of this was Cugini Sparkling Grape Juice from Ponzi Vineyards. When made well, these products or other wine styles can help gain market share. However, quality is important in these products, too. They cannot be an outlet for flawed product with a hope of gaining reputation.

- Scaling Up Requires Adaptation. One challenge that is noticeable in any food production facility is the natural growing pains that come with increasing production volume: the product does not taste the same, parameters cannot be monitored the same was as they had in the past, techniques need to be altered, more staff is required for maintenance, etc. The greatest lesson I learned in Oregon is to prepare for these changes. Search out industry expertise that can help you avoid mistakes.

While not a growing pain, per se, but something I noticed: many of the productions stayed relatively small over time. Most fermentations were taking place in 2 – 3 ton fermenters, and there was a general preference to keep processing operations on the smaller side.

This allowed greater control over individual lots and flexibility in blending. Most productions maintained a portfolio of under 20 wines, but may have had hundreds of separate lots or barrels that were blended together to create a specific wine.

What was interesting to me was to taste the various vineyard-designated Pinot Noirs and find very dramatic differences (and preferences) for the wines. Blending is a valuable tool to winery, and having the knowledge of how to utilize this technique can be quite advantageous to an emerging region, especially one with a varying annual climate.

Three: Gain Experience

This is a big one, and it can seem daunting. However, all wine regions stem from humble beginnings. It is possible to gain experiences that help shape the quality of winemaking over time.

Harvest Hops: Harvest hopping involves jumping between the north and south hemispheres to participate in harvests (the southern hemisphere harvest in our winter months). Many people on the west coast utilize a few years of harvest hopping to gain experience and knowledge about various winemaking practices. This not only improves an individual’s education, but also provides confidence in the cellar. Not to mention that the enhanced awareness of wine quality from a different region improves the winemaker’s sensory perceptions.

Educate Children That May Take Over the Family Business: If your children have an interest in production, make them get an education in the area before signing them onto the family business. Most of the successful wineries require future generations to get some sort of education before joining the family business, and in the case of production, many require their kids to go oversees to get other production experiences that can help grow and change the family winery. This not only helps progress the business, but facilitates long-term planning.

Attend Educational Events: One large difference that I saw in Oregon compared to other wine regions is the value they place in educating themselves routinely. People make a large effort to attend research-based and trouble-shooting meetings on an annual basis. They recognize the value in education and that there is always something new to learn.

If you would like to be better aware of educational and research opportunities in Pennsylvania:

- Sign up for the “Penn State Extension V&E News” listserv

- Watch for Penn State Extension events here: http://extension.psu.edu/food/enology

- Attend the Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA) Annual Conference and PA Wine Marketing and Research Board (WMRB) Symposium.

- Participate on an industry board listed above.

- Watch for educational tidbits on Penn State Extension Enology’s Facebook page

- Continue using the “Wine & Grapes U.” blog site: psuwineandgrapes.wordpress.com

Train Your Palate: This is a key skill that is required to make high quality wines. It’s also a great skill to learn to enhance selling strategies to consumers. Knowing wines pertaining to various regions and producers expands your palate memory. From a winemaking perspective, it can help alter processing decisions to tailor the style of your wine. From a retail perspective, it can help more formally communicate with consumers and make more wine suggestions (from your winery) that is tailored to their preferences.

Practical Applications for Aroma Development in Wine

By: Denise M. Gardner

This post is a follow up from a previous Pennsylvania Quality Alliance (PQA) meeting featuring Alain Razungles. An introduction to wine aroma and sensory can be found here: http://bit.ly/WineAromaSensory This is part two of a two-part series. Part one focused on specific points and studies that Alain Razungles, French enology professor, discussed during his visit to the eastern U.S. You can review Alain’s talk by visiting the Penn State Extension Enology website here. Part two emphasizes pratical applications of those points and how to utilize the information from Alain’s talk in a vineyard or winery.

Picking Grapes for Flavor

A good quality measure that a winemaker can utilize in the winery is learning to pick grapes for flavor. More often than not, grapes in the east are picked on Brix and pH readings over a progression of time. In the Mid-Atlantic, sometimes the need to pick due to weather restrictions also occurs. For those years in which growers can hold grapes on the vine and wait, a greater flavor development of that variety may occur (Coombe and McCarthy 1997).

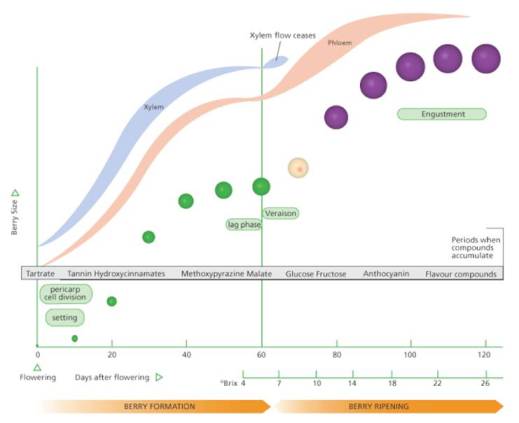

As stated in Alain’s presentation, aroma/flavor development is one of the last ripening stages to occur in the grape berry. Coombe and McCarthy (1997) labeled the aroma/flavor ripening stage as engustment, which occurs after sugar (Brix) accumulation has stopped or severely slowed down. This ripening stage is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Grape berry development and ripening. Image is from Jordan Koutroumanidis (Winetitles), and previously featured in “Understanding Grape Berry Development” by James Kennedy, Practical Winery & Vineyard Journal (July/Aug 2002)

Although difficult to detect aroma/flavor development through most analytical means, growers and winemakers can train themselves in [grape] Berry Sensory Analysis, as outlined by the Institut Cooperatif du Vin (ICV) or by using the Winegrape Berry Sensory Assessment in Australia guide by E. Winter, J. Whiting, and J. Rousseau (ISBN: 9781875130412). Grape berry sensory allows an individual to better evaluate wine grapes using visual, tactile, and taste sensations that change as a grape ripens. One of those key attributes is flavor.

Overall, berry assessment is not very difficult, but it does require adequate training and practice. Berries are analyzed on a 4 point “maturity-indication” scale for several attributes that indicate pulp, skin, and seed ripeness. Sensory analysis is completed with a standardized record system that allows winemakers to easily document each grape tasting. This visual representation reflects when a grape variety comes into its engustment stage. Generally, the winemaker would choose to pick at this stage, as engustment remains active for a short length of time, usually a few days. Harvesting grapes within this engustment stage allows for the greatest free aromatic potential of the future wine.

The Role of [Aroma] Precursors in Wine – Protect Wine Aroma/Flavor

Although many people came away from Alain’s talk wanting to measure aroma precursor concentrations in berries and juice, as these precursors indicate the aroma potential of the wine after fermentation is complete, the analysis is quite complicated and time consuming. Dr. Bruce Zoecklein from Virginia Tech has featured many articles on aroma-precursor and glycoside development, concentration, and analysis for wine grape varieties (http://www.vtwines.info/).

Although difficult to analyze in a precursor form, these non-aromatic compounds are present in grapes and juice, and are converted to aroma/flavor compounds during fermentation. Therefore, conservation of aroma/flavor precursors in grapes and wines is related to the production of volatile aroma/flavor compounds during fermentation and through wine aging. Retention of these precursors and their corresponding volatile compounds should remain an emphasis during wine production from harvest through retail.

Ensuring that grapes have properly ripened beyond sugar accumulation and into engustment will allow the fermentation to produce a varietal wine. Consequently, berry ripeness will determine the starting material for the future wine and dictate the quality of future aroma/development through the winemaking process. If the grapes are in poor condition, the chances of producing a poor quality wine are high. Rots, mildews, molds, bacteria, and immature grapes all contribute to off-flavors in the wine. Additionally, lack of crop maintenance can produce or retain off-flavors that may mask any varietal characteristics.

A lot of aroma/flavor development is determined by yeast and bacteria selection for primary and secondary fermentation. Yeast and bacteria (such as malolactic bacteria) utilize some aroma-precursors during fermentation, which contributes to the final aroma/flavor of the wine. Additionally, other secondary metabolic pathways in yeast and bacteria will produce aromas/flavors indirectly (Swiegers et al. 2005).

Aroma/flavor compounds are generally volatile, meaning that they can easily escape from the wine in a gas phase, and are sensed by the nose or mouth of a human. During fermentation, some aroma/flavor is lost due to the rapid production of carbon dioxide. This phenomenon is quite noticeable with early production of hydrogen sulfide, which blows of during rapid stages of fermentation and is then lost by the time fermentation is complete.

However, temperature also influences the volatility of aroma/flavor compounds. The higher the temperature, the more aroma/flavor compounds escape into the gas phase. White wines are especially susceptible to aroma/flavor loss during and after fermentation as their volatile aroma/flavor compounds are easily blown off with higher temperatures. Small changes to white wine production can help enhance wine quality with aroma/flavor retention through bottling and retail:

- The utilization of temperature controlled fermentations is an option for retaining aroma/flavor of the finished wine. Whites should be fermented below 65°F(18°C) to retain their aroma/flavor. Reducing the ambient temperature surrounding the fermentation vessel slows down the fermentation, which inhibits the fermentation from reaching high internal temperatures and retains aroma/flavor of the final wine.

- Keep white wines fairly unexposed to oxygen helps preserve aroma/flavor in the wine. Oxygen depletes aroma/flavor in two main ways. First, it contributes to the depletion of varietal aroma/flavor compounds that blow off into the gas phase. Second, oxygen is a key requirement for oxidation and other spoilage processes. These processes contribute their own aroma-active compounds that can compete with and mask the varietal aroma/flavor compounds that remain intact. Production causes of oxygen ingress include pumps, storage (headspace in tanks or barrels), racking, fining, and bottling.

- Maintaining proper sulfur dioxide levels through longer term wine storage will stabilize the wine chemically, which will protect the aroma/flavor composition of that wine as well. Free sulfur dioxide levels should be monitored and analyzed on an every-other-week to every-three-weeks basis, and more frequently if tanks contain headspace.

The Role of Dimethyl Sulfide (DMS) in Red Wines

Although DMS is a fruit flavor-enhancing compound at very low concentrations, it can also be incredibly detrimental to wine quality in “higher” concentrations, depending on the wine variety and its chemical composition. Alain demonstrated that Syrah, a variety that naturally contains DMS as part of its varietal aroma/flavor composition, when first sniffed had an earthy-based aroma, but with incorporation of oxygen (i.e. swirling in the glass), it became very fruity and jammy (Segurel et al. 2004).

Although DMS is appears to be a prevalent aroma compound in Syrah, much like 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol (3MH) is in Sauvignon Blanc, it is not a realistic additive for wines. It is, after all, a sulfur-containing compound that can contribute to a reduced or stinky nose in wine. Most winemaking practices are designed to avoid accumulation of sulfur-containing compounds like DMS because these compounds are difficult to control and often mask fruitiness of wines.

Even though sulfur-containing compounds are essential for yeast metabolism, if produced in excess they do cause a relatively undesired aroma/flavor in wine. Humans vary greatly in their ability to sense these compounds. While one individual many not smell the sulfur-containing compound, another may be overwhelmingly appalled by its aroma at the same concentration. Some of the more common sulfur-containing compounds that are aroma-active are listed below.

Table 1. Table 1: Concentrations of aroma active sulfur-containing compounds in a normal wine versus a reduced with perception threshold concentration comparisons. Table is adapted from of Darriet et al. 1999, which was provided during Alain Razungles’ talk in July 2012.

These compounds have very low detection thresholds (<30 ppb), which means it does not take a lot of a given compound to be sensed by most people (Table 1). It has been proposed that hydrogen sulfide can give rise to many sulfur-containing compounds (Sweigers et al. 2005). Additionally, many are present in the grapes as cysteine-conjugates, a form of sulfur-containing non-aromatic precursors (Sweigers et al. 2005). The formation of these compounds is somewhat debateable in the research literature. However, it is generally acceptable to assume that winemakers do not want to accumulate sulfur-containing compounds in their odor-active form.

How does one avoid the over production of odor-active sulfur-containing compounds?

- Proper YAN management during primary fermentation to reduce potential hydrogen sulfide formation

- Inoculate for MLF immediately following primary fermentation to avoid native MLF associated off-flavors

- Avoid long term lees contact with fruity wines

Closing Remarks

When it comes to wine, flavor development starts in the vineyard. All viticultural decisions affect the final flavor profile of the grapes, which are the starting product for the wine. For example, research has shown that over-cropping, especially Vitis vinifera varieties, can lead to increased prevalence of green flavors. In excess, these flavors are undesirable in wine as they mask the fruit aromas/flavors. Management decisions in the vineyard can ultimately lead to lesser production of green flavors through strict crop thinning practices. These decisions must start in the vineyard because the flavor problems they cause are not always easily manipulated in the wine.

Many wine processing decisions can also alter wine flavor. Whether the flavor alteration is small or large will depend greatly on the processing decision and when it is implemented. For example, improper management of headspace in tanks or barrels will have a large effect on the wine’s flavor. In comparison, altering yeast selections may have a small effect on the final wine flavor. Such decisions require a comfort level with winemaking and a firm understanding of flavor nuance in wine.

Although these two papers touch upon specific flavors in wine, there are a series of other resources available to winemakers that discuss wine flavor development:

- WineFlavor 101 Workshop Series through UC Davis: http://wineserver.ucdavis.edu/

- Bruce Zoecklein’s Enology Grape Chemistry Group: http://www.vtwines.info/

- Pennsylvania Wine Quality Initiative (WQI) workshops through Penn State Extension Enology: http://extension.psu.edu/enology

References Cited

Coombe, B.G. and M.G. McCarthy. 1997. Identification and naming of the inception of aroma development in ripening grape berries. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 3:18-20.

Darriet, P. 1999.

Segurel, M.A., A.J. Razungles, C. Riou, M. Salles, and R.L. Baumes. 2004. Contribution of dimethyl sulfide to the aroma of Syrah and Grenache Noir wines and estimation of its potential in grapes of these varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52: 7084-7093.

Swiegers, J.H., E.J. Bartowsky, P.A. Henschke, and I.S. Pretorius. 2005. Yeast and bacteria modulation of wine aroma and flavour. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 11:139-165.

It’s Never Too Early to Start Thinking about Harvest

By: Denise M. Gardner

While most of us are in the thick of the grape growing season, the start of harvest will be knocking on our doors all too soon. Preparing for harvest can never start early enough! Below is a list of recommendations for growers and winemakers to consider during prior to the harvest season.

Winemaking Supplies

July is just around the corner, which means that many wine supply companies are about to offer “Free Shipping in July” specials. Not only is this a cost savings opportunity for many wineries, but it also provides a chance for winemakers to adequately plan for their fermentation needs.

Check with your current supplier to evaluate options for shipping and potential new products to incorporate into your winemaking portfolio.

Berry Sensory Analysis

Ironically, I found 2 articles in the July 2015 edition of Wine Business Monthly (WBM) related to why berry sensory analysis is important to both growers and winemakers. The method first introduced to the wine industry by the Institut Francais de la Vigne et du Vin (IFV), has been integrated into wine regions throughout the world. If you are lucky enough to obtain a copy of Monitoring the Winemaking Process from Grapes to Wine: Techniques and Concepts, you’ll find detailed instructions on vineyard sampling, matching grape ripening characteristics to the future wine, and an explanation on berry sensory analysis (pg. 27).

Berry sensory analysis involves analyzing the component parts of the berry (skin, pulp, and seeds) separately – both visually and through a sensory evaluation – to monitor ripeness of berries beyond the capabilities of many other analytical techniques. It is not a method which involves selecting a berry or two from a cluster, popping them into one’s mouth, and giving a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” evaluation to ripeness. There is a strategic approach, including proper vineyard sampling, to evaluate ripeness.

In fact, berry sensory analysis goes beyond measuring the typical analyses (Brix, pH, TA) to indicate ripeness. While the sensory technique may appear complicated at first, it can easily be mastered – quickly – with a little practice and good use of record keeping.

As noted by Mark Greenspan in his recent July 2015 WBM article, “Harvest: The Final Vineyard Decision,” many winemakers find it daunting to go out into a vineyard and regularly monitor the sensory changes affiliated with grape berry ripening. Therefore, this offers an unique opportunity for growers and winemakers to work together. Either both parties can learn the proper techniques affiliated with berry sensory analysis and switch regular responsibilities affiliated with recording ripeness development, or growers can adequately sample vineyards and routinely deliver berries to the winemaker. Evaluating berries together allows for open communication between growers and winemakers in terms of sensory expectations for a given variety.

Need more information on berry sensory analysis before diving into a more formal training process? Look no further!

2006 WBM article by Mark Greenspan titled, “Assessing Ripeness Through Sensory Evaluation”

2006 Wines & Vines article by Thomas Pellechia titled, “A Better Berry Evaluation?”

Curious about the berry sensory analysis technique? Check out these explanations and protocols:

“Method for Sensory Analysis of Grapes” on the University of Minnesota Enology Blog

“Berry Sensory Analysis” by Bruce Zoecklein from the Enology Grape Chemistry Group at Virginia Tech

Finalize Grower and Juice Broker Contracts

The issue of grape negotiations comes up every harvest season. While many individuals in the industry still use a common handshake or acknowledgement of a deal through a phone call to confirm grape sales or purchases, I annually hear stories from both parties indicating a lack of satisfaction regarding harvest deals.

It is important to recognize that growers and winemakers have two different end goals in mind by the end of a growing season. Obviously, this can create points of tension in any negotiation if one party’s goals are not met to their liking.

In order to mediate many of these negotiations, the use of contracts between growers and wineries is often recommended.

eXtension has a document, written by Chris Lake, regarding the definition of grape and winery contracts, the end goals pertaining to both parties, and the essential topics of coverage related to a contract, which can be found here: http://www.extension.org/pages/62146/contracts-between-wineries-and-growers#.VYrlK_lVhBc. Additionally, Chris has listed several resources for more information for those that are interested in developing future contracts.

Bruce Zoecklein from Virginia Tech’s Enology Grape Chemistry Group has also developed a sample contract available for grower and winery use.

Preparing the Cellar and Lab

The summer months are perfect opportunities for wineries to engage in harvest preparation. These prep steps include:

- Finishing up bottling to allocate space for the incoming new material

- Finalizing grower contracts (see above)

- Check cellar equipment to ensure it is working properly

- Clean and sanitize any equipment or environmental surfaces

- Train incoming, new staff members proper standard operating procedures (SOP’s) and safety operations

- Make sure that there are enough analytical supplies to sustain your operation through harvest

- Check and calibrate all lab equipment

- Train all harvest interns and cellar/lab personnel how to handle harvest equipment and/or lab equipment

- Review any SOP’s or safety protocols – for the cellar and lab – to evaluate if they should be updated before harvest

For further information on general harvest preparation steps, please see the Penn State Wine Made Easy Harvest Preparation fact sheet, or Dr. Muli Dharmadhikari’s detailed explanation on harvest preparation steps.

![Make sure cellar equipment is properly cleaned and in good working order before harvest. [Opus One cellar, 2004.]](https://psuwineandgrapes.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/image013.jpg?w=519)

Make sure cellar equipment is properly cleaned and in good working order before harvest. [Opus One cellar, 2004.]

There are many opportunities during the “off-season” for wineries to adequately enhance safety operations in the winery. In general, all employees should be adequately trained on safety procedures, the use of safety equipment (e.g., how to wear safety equipment and when to wear it), and know the proper steps in handling an emergency (i.e., where the phones are located on the production floor, where the First Aid Kit is located, etc.).

As fermentation offers one well- known hazard to a winery – the rapid development of carbon dioxide – the summer months may be a good time for wineries to install carbon dioxide meters.

Ensure that proper equipment and instructions for making sanitizers is available to (and known by) all cellar employees.

Additionally, wineries should double check ventilation systems to ensure proper ventilation in the cellar area during the chaotic harvest season.

For more information on OSHA related safety techniques or developing a safety training program for your winery, please visit: www.osha.gov.

Hard Cider Production Resources

By: Denise M. Gardner

On January 13th, Penn State Extension hosted their first Hard Cider Production workshop at the Fruit Research and Extension Center (FREC) in Biglerville, PA. The day was filled with various speakers from New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia with perspectives from various Mid-Atlantic state hard cider industries. Topics were focused on the economics of hard cider production in the Mid-Atlantic, experiences with growing apples for hard cider production, how to produce hard cider, and orchard considerations for new hard cider apple variety growers.

Attendees of the 2015 Hard Cider Production workshop tasting a series of hard ciders from around the world.

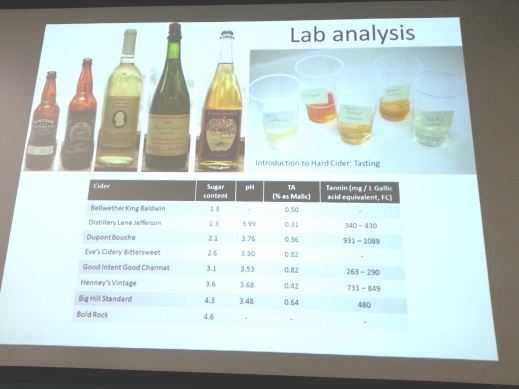

The program was incredibly successful and included a tasting of 8 different hard ciders, emphasizing the variation in styles and flavor currently available on the market:

- Bellweather King Baldwin Hard Cider: With the least residual sugar, this light weight, well-balanced, dry cider had a lingering finish of citrus and apple flavors. For those getting into the industry, this is a good example of a well-made, clean hard cider.

- Distillary Lane Jefferson Hard Cider: One of the oakier ciders provided during the tasting, with prominent vanilla, oak and light apple flavors.

- Dupont Bouche Hard Cider: An amber color with a Brettanomyces aroma and flavor dominating the cider. Sweetness was well integrated and matched well with the barnyard flavors. A good example of Burgundian ciders.

- Eve’s Cidery Bittersweet Hard Cider: Floral with complementing cooked apple flavors, carbon dioxide was light and tasted less sweet than intended due to its tannic mouthfeel.

- Good Intent Good Charmat Hard Cider: A local, PA-produced cider with light petulance and butterscotch notes in addition to the apple juice aroma. Semi-sweet.

- Henney’s Vintage Hard Cider: This golden-yellow cider was the subject of much discussion. Flavors of Band-Aid and nailpolish dominated the nose, but had more apple flavor on the palate to supplement the acidic, acetic acid flavors.

- Big Hill Standard Hard Cider: Produced from a local cidery in PA, the light cooked apple favor of this cider was prominent with its sweetened mouthfeel.

- Bold Rock Hard Cider: A producer from New York that is producing a more commercial style of hard cider. This hard cider emphasized vanilla and light apple notes with a well-integrated and sweetened finish.

Analysis details of hard ciders tasted during the Penn State Extension Hard Cider Production 2015 workshop.

Attendees had many focused questions in various topic areas, which acknowledged the lack of resources available for the hard cider entrepreneur. The following lists a series of resources that were provided at this workshop that may be good starting points if you or your business is looking into hard cider production.

Consider Attending the Next Penn State Extension Hard Cider Production Workshop

This workshop focused on individuals that were thinking about or in the planning stages of building a business around hard cider production.

Text Books on Hard Cider Production

“Sweet and Hard Cider” by Annie Proulx and Lew Nichols

“The New Cider Maker’s Handbook” by Claude Jolicoeur

Online Publications for Apple Growers

“Antique Apples for Modern Orchards” by Ian Merwin, NY Fruit Quarterly 2009

“Growing Apples for Craft Ciders” by Ian Merwin (future issue of NY Fruit Quarterly)

WSU Bulletin on Cider Program in Mt. Vernan

Online Publications for Hard Cider Production

Hard Cider Production at Virginia Tech

Fermentation Protocols from Washington State University

Cider Juice Analysis Protocol from Washington State University

Scott Labs Hard Cider Fermentation Protocol

Cider Organizations and Conferences

US Association for Cider Makers

Online Information or Websites

Scott Labs Hard Cider Handbook

Penn State Extension Fruit Times

Old Time Cider (with additional resources)

Other Extension Programs Useful for the Hard Cider Producer

Cornell University: Cider & Perry Production – Principles and Practice Workshop

Penn State Extension – Sanitation Short Course

Warwickshire College Hard Cider Production Workshop

Northwest Agricultural Business Center Hard Cider & Perry Production Workshop

Enology and Viticulture course coming to Gettysburg Campus

By: Bob Green, HACC Enology & Viticulture Program Director

Beginning August 18th, HACC will be offering one of the courses in its Enology and Viticulture program at the Gettysburg Campus for the fall semester. The course, ENVI 253 Sensory Evaluation II, is the second of two sensory courses offered in the program, and explores the flavor profiles of wines made from grapes grown in Pennsylvania and other regions on the East Coast and compares them with archetypal wines. Students will learn about the different species and varieties of wine grapes, their flavor profiles, origin, traditional grape growing regions, and how a hot or cold climate can affect the grapes, and thus, the wine.

The course is a blended course, which combines online lecture materials with hands-on sessions at two weekend “camps”. This format allows convenient online access to classroom lectures and materials, while providing two important face to face sensory camps with the instructor and the other students. Both traditional, full time, students and non-traditional students with full time jobs and other responsibilities can take advantage of this format. The two camps meet on the weekends of Sept. 27-28, and Nov 8-9, 2014 in the Robert C. Hoffman Community Room on the HACC Gettysburg Campus. A $55 course fee is required, in addition to the tuition, for the purchase of wines that will be tasted during the camps. Students will also be evaluating wine on their own time, and keeping a wine evaluation journal throughout the semester.

Some knowledge and experience with wine tasting and sensory evaluation is required for this course. Within the program, the Sensory Evaluation I course is a prerequisite. The instructor can override this prerequisite requirement for individuals that have the experience and interest, and are not enrolled in the program.

The Enology and Viticulture program at HACC was created to provide trained employees for the wine and grape industry in Pennsylvania and surrounding states on the East Coast. Commercial vineyards and wineries are thriving, and the industry continues to grow as new vineyards are planted, and wineries are built. Foremost for these entrepreneurs is the production of high quality wines, requiring a knowledgeable and skilled labor force. To meet this need, HACC developed a curriculum that is tailored to the conditions that make this area and its wines distinctive.

The program offers three options for study: completion of an associate degree; completion of a certificate; or auditing individual courses for personal or professional enrichment. You can enroll in the college online by visiting the HACC website (www.hacc.edu). Once enrolled, you are also able to register for classes online, as well.