Adding Bubbles to your Hard Cider

By: Denise M. Gardner

At the recent Sparkling Wine Production workshop in PA, our speakers talked a lot about various production methods used to incorporate carbonation into [grape] wine. But what about for a sparkling hard cider?

For base cider production, the objectives are similar to that of sparkling wine: create a fresh and fruity alcoholic product with high acid, good apple flavor, and a clean nose and palate. Nutrient strategies during primary fermentation should be considered by the cider maker, as flaws like hydrogen sulfide (H2S) or general reduction (sulfur-containing off-odors) will diminish the enjoyability of the product. Carbonation has the tendency to enhance the perception of flaws. Therefore, it goes without saying that sanitation is generally very important during this process in order to obtain a clean product suitable for carbonation.

For producers that struggle with obtaining high-tannin apple varieties, sparkling [hard] cider may offer an alternative to the establishment’s product portfolio. In sparkling wine production, low tannin concentrations and perceptions are often preferred, as too much tannin may create a harsh mouthfeel with the additional sensory contribution from the carbonation. This concept may also be applied to sparkling hard ciders.

Malolactic fermentation, MLF, or partial-MLF is determined stylistically by the cider maker. Stabilization including protein stabilization and clarification should be completed prior to carbonation. Dependent on the method of carbonation, sulfur dioxide additions may be required at this step, too.

Dependent on the size and capabilities of the cidery, most sparkling wine production techniques can be utilized by hard cider producers to enhance the carbonation of a hard cider product.

- Bottle conditioning

- Traditional method (Méthode Traditionelle, previously referred to as Méthode Champenoise)

- Charmat, or Tank, method

- Forced carbonation

Bottle conditioning is often used by home brewers as a way to incorporate carbonation in each bottle inexpensively. The concept is relatively simple: add yeast and some additional sugar to each bottle so that the yeast will ferment the sugar while in the bottle. Due to the fact the bottle is sealed, the carbon dioxide developed through fermentation will be retained as carbonation in the bottle. While this is often a preferred method for extremely small operations, the results of this technique are often quite variable, which increases inconsistency amongst the product. Additionally, the resultant product is not typically clear and residual yeast will settle at the bottom of the bottle. Sometimes, this noticeable cloudiness and precipitate is not preferred by consumers. For a good explanation on bottle conditioning, please consider reading this document by Northern Brewer: https://www.northernbrewer.com/documentation/AdvancedBottleConditioning.pdf

The Traditional Method (Méthode Traditionelle) is the common practice that is associated with Champagne production. In this case, carbonation is produced in the bottle by a second yeast fermentation. The difference between this method and bottle conditioning is that the residual yeast is removed through disgorgement prior to the addition of a final sugar and stabilization liquid, called the dosage. This production technique has previously been discussed through the blog post: The Bubbles: Basics about Sparkling Wine Production Techniques, which you can access through the link.

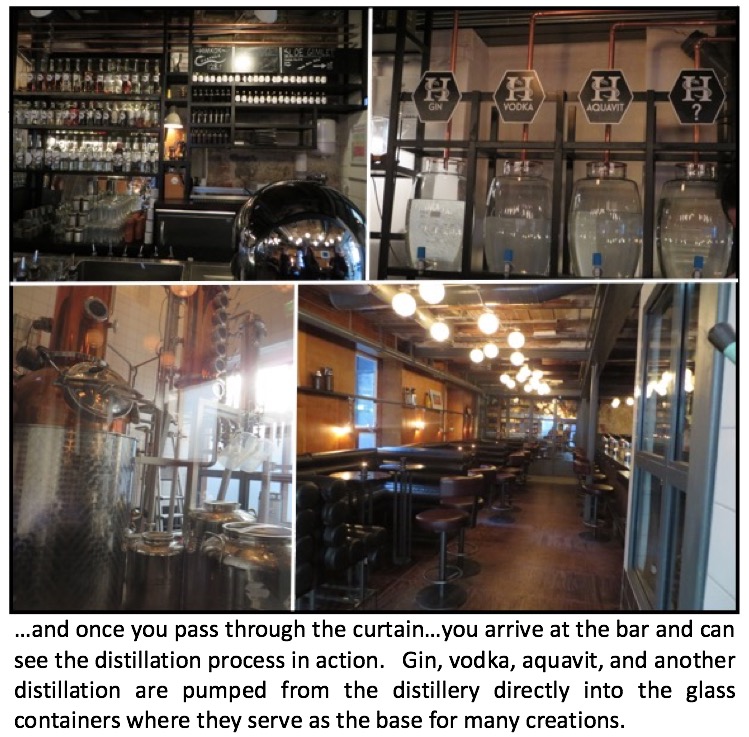

Two ways of riddling sparkling wine at Korbel Wine Cellars, CA. This process is often used during the Traditional Method of sparkling wine (or hard cider) production. Photos by: Denise M. Gardner

Although many wine fermentation suppliers offer various product addition options for hard cider producers, Scott Labs currently offers The Cider Handbook to make addition decisions easier for producers. Their current product portfolio also features encapsulated yeast products, which some sparkling wine producers have had success in using when utilizing the traditional method of production.

Additionally, this style of sparkling hard cider can use similar equipment utilized by sparkling wine producers.

The Charmat Method (Tank Method) is becoming more popular amongst local wineries, and can also be utilized by sparkling hard cider producers. Here, the secondary yeast fermentation occurs inside a sealed tank and then the hard cider is racked off of the lees into a second pressurized tank. The racked cider maintains the carbon dioxide, carbonation, and the second tank it is racked into can contain the final dosage for the whole volume of hard cider in order to manipulate final sweetness and stabilization. The advantage to this system is that it retains the fruitiness associated with the product and requires less labor compared to dealing with hundreds of bottles in the Traditional Method. The downside to this processing option is the initial cost of processing equipment required to retain pressure inside a tank. As with the Traditional Method, details pertaining to the Charmat Process were previously discussed in the blog post: The Bubbles: Basics about Sparkling Wine Production Techniques.

Finally, one of the easiest methods for obtaining carbonation in your product is through the use of forced carbonation. Some hard cider producers have found success in carbonating kegs of hard cider or working with local wineries that offer carbonation services. With this method, the hard cider should be fully produced, stabilized, back sweetened (if applicable) and filtered by the time it is carbonated.

Reviewing YAN and Hydrogen Sulfide: Part 1

By: Denise M. Gardner

Yeast assimilible nitrogen (YAN) is the sum of the amino acid and ammonium concentrations available in the grape juice at the start of fermentation. Typically, the amino acid proline is not included in the reported amino acid content as it is not readily utilizable by yeast cells.

The amino acid component of YAN is often referred to as the “organic” YAN form. In contrast, the ammonium ion content is referred to as the “inorganic” YAN form and may be written in its ionic abbreviation: NH4+. Due to the fact that ammonium is only connected to a series of protons (H+ ions), it tends to be easier to move in and throughout the yeast cell to be consumed during fermentation (Mansfield, 2014). When these two components (organic + inorganic) are added together, the resultant value is the YAN, written with the units: mg N/L.

The winemaking challenge associated with YAN is the fact that it is quite variable, and current research has not identified ways to change the YAN, predictively, in fruit through the manipulation of vineyard practices. YAN varies by vintage year, grape variety, cultivar, and with the use of various vineyard management practices. In Penn State’s research vineyards, ~1 acre in size and containing 20 different wine grape varieties, YAN values ranged dramatically each vintage year amongst the various wine grape varieties. On any given vintage year YAN values ranged from low (<100 mg N/L) to high (>300 mg N/L) amongst the varieties grown in that one site.

The variability associated with YAN provides a secondary challenge to winemakers: the lack of predictability associated with hydrogen sulfide formation during primary fermentation due to unfulfilled nitrogen needs by wine yeasts.

What does YAN have to do with Hydrogen Sulfide?

Winemakers often talk about YAN in relation to hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as the two have been associated with one another throughout primary fermentation. Although there are several potential causes of hydrogen sulfide formation during wine production, some of which we will talk about in our Part 2 series, nitrogen imbalance has been one of the factors that winemakers can influence through production. Unfortunately, there is no way to ensure that a wine will not produce hydrogen sulfide by the end of fermentation, but treating wines with proper nutrient supplementation can help minimize the incidence of hydrogen sulfide production during primary fermentation.

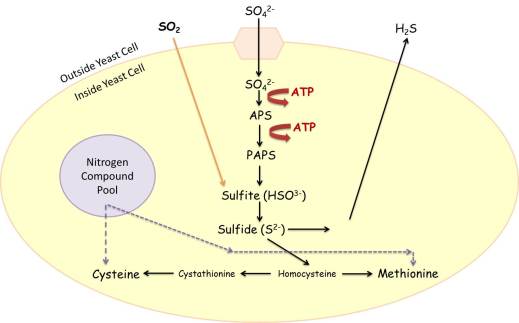

Hydrogen sulfide is produced by the yeast cell via the sulfate reduction pathway (Figure 1). While I know this figure looks scientifically daunting, we can try to simplify its purpose to discuss how hydrogen sulfide is released into wine. Sulfate (SO42-), naturally abundant in grape juice (Eschenbruch 1974), is transported into the yeast cell for amino acid (cysteine and methionine) development, which are naturally lacking in concentration in grape juice (Bell and Henschke, 2005). Energy is used by the yeast (represented as ATP in Figure 1) to chemically alter the structure of sulfate in order to make it useable by the yeast cell. This useable form can be seen as sulfide (S2-) in the image below. Using nitrogen, which is required to make an amino acid, the sulfide content is depleted as cysteine and methionine amino acids get produced. Therefore, as sulfide reserves are depleted, cysteine and methionine contents generally increase to be used for building proteins that will be needed by the existing or new yeast cells.

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) plays a role in the sulfate reduction pathway in that it bypasses the transport mechanism required to bring sulfur into the yeast cell. It other words, it can diffuse across the cell membrane and into the internal parts of the yeast cell. Sulfur dioxide will get chemically altered to be made into the useable sulfide , S2-, form as well. Therefore, fermentations that contain a high concentration of sulfur dioxide at the start of fermentation have the potential to increase the utilization of sulfur dioxide during yeast metabolism.

These processes function normally until a depletion of nitrogen (from the nitrogen pool) or an accumulation of sulfide develops in the yeast cell.

If there is not enough nitrogen (low YAN fermentations) available to make the sulfur-containing amino acids (cysteine and methionine) then, eventually, the yeast cell will not be able to continue manufacturing these amino acids. In this situation, the sulfide concentration generally starts to increase within the yeast cell.

The chemical form sulfide, however, is toxic to the yeast cell and thus, the yeast will try to eliminate it from its internal structures. Therefore, when sulfide concentrations get too high, the yeast will diffuse this across its cell membrane into the surrounding media: the fermenting juice. When hydrogen sulfide concentrations get high enough in the fermenting juice, winemakers can often sense the rotten or hardboiled egg aroma associated with the compound.

What if there is too much nitrogen?

In contrast, too much nitrogen (high YAN fermentations) can also be problematic. Higher concentrations of the inorganic component of YAN can lead to a high initial biomass (population) of yeast. The rapid increase in yeast populations can lead to nutrient starvation by a majority of the yeast when the wine is about almost finished completing fermentation. With a large biomass of yeast incapable of obtaining the proper nutrient (nitrogen) content to grow and reproduce, hydrogen sulfide development can result. This is due to the fact that there is a large population of yeast in situations in which there is not enough nitrogen to support their growth (i.e., there is not a lot of food to go around for all of the yeast cells). With hydrogen sulfide development occurring late in primary fermentation, it is obvious that the winemaker would become concerned with hydrogen sulfide retention by the time fermentation is fully complete.

Too much nitrogen can also cause other quality problems. Due to the excess amount of available nutrients, yeast can grow and reproduce quickly, which often leads to very rapid or very hot fermentations. The speed of fermentation, of course, can affect the aromatics and quality of the wine (i.e., fast fermentations often lead to simpler aroma and flavor profiles). This may not be an issue with some styles of wine, but for many white wine or fruit (other than grapes)-based fermentations, aromatic retention is often a priority by the winemaker.

Due to the fact the initial YAN is so high, all of the nitrogen contents may not be utilized by the yeast population by the end of fermentation, and could remain in suspension in the finished wine. As yeasts begin to autolyze, all of their inner components, including the remaining nitrogen content, will become available in the wine. The excess “food” could be available for other microorganisms (like acetic acid bacteria, lactic acid bacteria, or Brettanomyces), which could potentially lead to spoilage problems if the wine is not properly stabilized. Such spoilage is, obviously, detrimental to wine quality and undesirable by the winemaker. Alternatively, remaining nutrients could be utilized by malolactic bacteria or those wines that will be given tirage for sparkling production (Bell and Henschke, 2005).

Finally, higher YAN concentrations can lead to an increased risk of ethyl carbamate production in wine; ethyl carbamate is a known carcinogen that can give susceptible individuals headaches, or even respiratory illness. Ethyl carbamate is produced in a reaction between ethanol and urea (Bell and Henschke, 2005). The heavy use of DAP has also been linked to a higher potential risks of ethyl carbamate due to the fact that DAP inhibits the transport of amino acids into the yeast cells, and therefore, leaves a higher concentration of amino acids available that can potentially be altered into urea, a precursor for ethyl carbamate (Bell and Henschke, 2005).

The fact that excess nitrogen can be problematic during wine production should provide insight to winemakers to avoid over-supplementing their fermentations. Hence, it is often recommended to that winemakers measure and identify their starting concentration of YAN and supplement accordingly.

Nitrogen Supplementation

Nitrogen (nutrient) management and supplementation is not uncommon during primary fermentation as nutrients are an important component of yeast cell growth and metabolism. In the yeast cell, nitrogen is a required nutrient in the synthesis of amino acids and to build proteins that are used in the yeast cell walls and organelles, as discussed above. Without protein development, the yeast cell cannot live.

Winemakers can supplement their fermentations with nitrogen by adding nutrient supplements in the form of:

- Hydration nutrients (e.g., GoFerm, Nutriferm)

- Complex nutrients (e.g., Fermaid K, Nutriferm)

- Diammonium phosphate (DAP)

DAP is considered an inorganic form of nitrogen, while the complex nutrients may contain additional organic yeast components that contribute organic forms of nitrogen. Recall, above, that the inorganic form of nitrogen is more readily consumed by yeast, and it can be easily absorbed by yeast cells even as alcohol concentrations rise during primary fermentation. Amino acids, on the other hand, require energy expenditure in order to be brought into the cell through transport proteins located on the cell membrane. The presence of both alcohol and ammonium ions inhibit the transfer of amino acids from the juice into the yeast cell (Santos, 2014). Therefore, it is often recommended to avoid the addition DAP or products that contain DAP (i.e., Fermaid K, Nutriferm Advance) at inoculation and until after yeasts have the opportunity to best absorb amino acids. If you are looking for some guidance on when to add nutrients to your fermentation, please refer to our Wine Made Easy fact sheet on the Penn State Extension website.

Starting YAN Concentrations

Nonetheless, nutrient supplementation strategies are often based on starting YAN concentrations in the fruit. Due to the regular variability of YAN concentrations, winemakers are encouraged to measure YAN for each lot of grapes every year. This is often problematic for winemakers whom do not have the time to run the appropriate analyses associated with YAN or the financial resources to send samples to an analytical lab. Such challenges force many winemakers into a situation in which all fermentation lots are treated with the same repeated nutrient supplementation regardless of the starting concentration of YAN.

In previous Extension workshops, research from Cornell University on Riesling wine grapes found that they could accurately predict the harvest YAN when good field samples were taken within 2 weeks from harvest (Nisbet et al., 2013). In 2016, Cornell released a second publication that focused on YAN prediction models for Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, Merlot, Noiret, Pinot Noir, Riesling, and Traminette. While the prediction models were not recommended for regions outside of the Finger Lakes (where the data was sourced from for this study), they found that in some cases, YAN data could be obtained within 5 weeks of harvest (Nisbet et al., 2014). This extra flexibility in time can aid in obtaining accurate YAN results before the grapes reach the crush pad, which ultimately helps winemakers prepare for nutrient supplementation before the start of fermentation.

Until further research can provide predictive modeling for other wine regions, it is generally accepted that winemakers should measure YAN at or as close to harvest as possible.

YAN can be measured using the following the analytical procedures:

- Enzymatic methods for both primary amino acids and ammonium.

- Probe for ammonium ions.

- Formol titration

While the Formol titration is often preferred by many small wineries due to the lower start-up investment, the use of formaldehyde, a known carcinogen and lung irritant, in this protocol does require some consideration for laboratory safety. Additionally, the proper disposal of formaldehyde, a hazardous substance, can be an issue for many wineries.

Enzymatic methods by spectrophotometer definitely require a bit of experience in order to become more efficient in their use, which can be problematic for those operations that find measuring YAN too timely. Additionally, enzymatic kits have to be purchased fresh and have a small shelf life. The advantage of investing in a spectrophotometer, however, is that other enzymatic kits can be purchased to measure additional wine components including residual sugar, malic acid, and acetic acid.

Nonetheless, measuring YAN should be a consideration for wineries that struggle with hydrogen sulfide aromas by the end of primary fermentation. It is through the starting numerical value that winemakers can better manage and adjust nutrient supplementation strategies to help minimize the reoccurrence of hydrogen sulfide at the end of fermentation.

Nutrient availability during primary fermentation is only one potential contributor to hydrogen sulfide formation in wines. In the next blog post, we’ll explore other potential causes of hydrogen sulfide formation and how to best mediate the problem when it exists.

References

Eschenbruch. R. 1974. Sulfite and sulfide formation during winemaking – a review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 25(3): 157-161.

Bell, S.-J. and P.A. Henschke. 2005. Implications of nitrogen nutrition for grapes, fermentation and wine. Aust. J. Grape and Wine Res. 11:242-295.

Mansfield, A.K. Are you feeding your yeast?: The importance of YAN in healthy fermentation. Webinar. Feb. 2014.

Nisbet, M.A., T.E. Martinson, and A.K. Mansfield. 2013. Preharvest prediction of yeast assimilable nitrogen in Finger Lakes Riesling using linear and multivariate modeling. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 64(4): 485-494.

Nisbet, M.A., T.E. Martinson, and A.K. Mansfield. 2014. Accumulation and prediction of yeast assimilible nitrogen in New York winegrape cultivars. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 65(3): 325-332.

Santos, J. Getting Ready for Harvest: Yeast Nutritional Needs. Workshop Seminar. July 2014.

Sparkling Wine Production Workshop Coming to Penn State Extension – An Applied Workshop for Wine and Hard Cider Producers

By: Denise M. Gardner

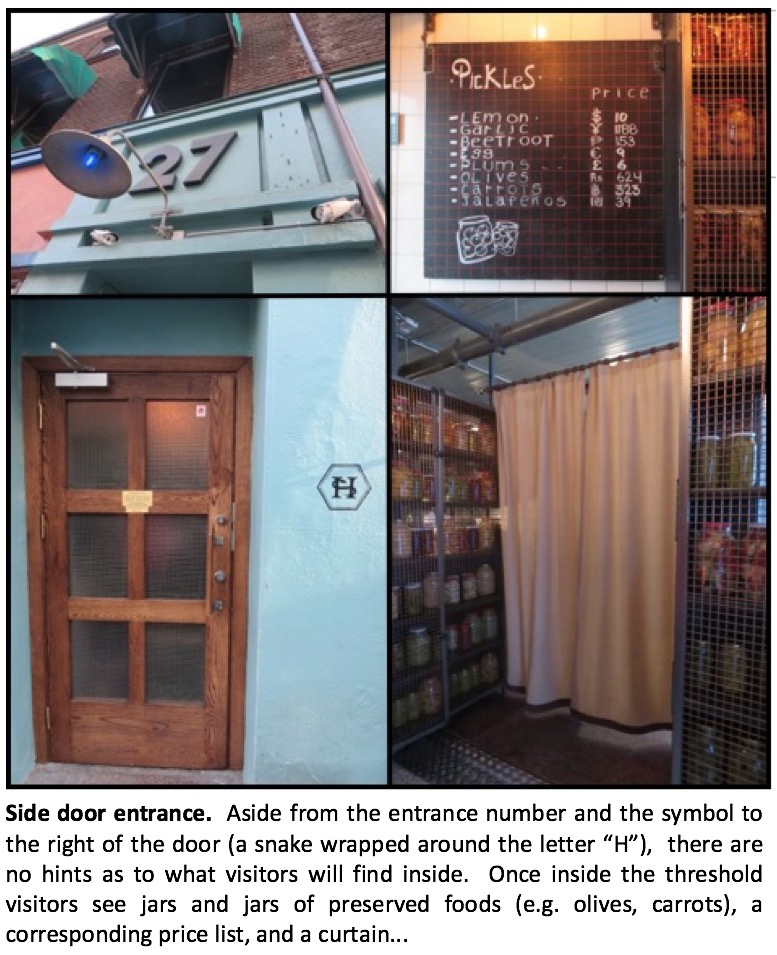

On March 7, 2017, Penn State Extension will host their first sparkling wine production workshop titled: Improving Bubblies in the Eastern U.S. at the Great Valley Penn State campus in Malvern, PA. (For more information on this program, please click on the title of the workshop.)

Figure 1: Sparkling wines at the tasting bar at Iron Horse Winery in CA. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Sparkling wine and sparkling [hard] cider production has become a hot topic for many Eastern producers. Some are interested in traditional sparkling wine production methods, occasionally referred to as méthode champenoise, while others are integrating modern approaches into their processing facilities to incorporate bubbles in their wines. The use of pressurized tanks, bottling under a pressurized system, and completing fermentation while retaining carbonation in a tank are all processes I have seen during my recent travels throughout the state. While pét-nats will not be covered at this workshop, there is a previous blog post pertaining to pét-nat production, which you can find here.

Sparkling wine production is a specific form of wine production that incorporates and retains carbon dioxide in the finished wine. The traditional method, méthode champenoise, includes the production of a base wine to about 10-11% alcohol and is bottled with the liquor de triage: a combination of sugar, yeast, and yeast nutrient. The bottle is sealed and as the second fermentation progresses in the bottle, the carbonation produced by the yeast is retained. Once this second primary fermentation is complete, the bottles are riddled (Figure 2) to collect the dead yeast cells within the neck of the bottle.

Figure 2: Two ways of riddling sparkling wine at Korbel Wine Cellars, CA. Photos by: Denise M. Gardner

Each bottle is then individually disgorged and the dosage is added to the wine for final sugar adjustment. Then, each bottle is sealed with a Champagne cork. Both Champagne and Cava are great examples of wines produced by the traditional method.

Other methods of producing and retaining carbon dioxide exist. In the Charmat method, once the base wine is finished fermenting, it is moved to a tank that can withstand pressure. The triage is mixed into the wine within the pressurized tank. When the second fermentation is complete, the spent yeast will settle at the bottom of the tank, and the wine must be racked under pressure to retain the carbonation produced by the second dose of yeast and sugar. The final dosage is added to the wine and then bottled under pressure. Italian Prosecco sparkling wines are great examples of the use of the Charmat process.

Others may utilize direct carbonation after the base wine has been completely finished. This can aid in creating a very fruit-forward style of sparkling wine or used to carbonate fruit wines or ciders.

This program will cover information for producers looking to get into sparkling wine or cider production or for those that would like to improve the quality of their products just a bit more.

We’ll cover basic harvest parameters (i.e., Brix, pH, TA and grape flavors) associated with traditional sparkling benchmark producers and discuss the general production and chemical composition of the base wine used to create sparkling products.

Additional speakers include Jerry Forest, the founder of Buckingham Valley Vineyards, Steve DiFrancesco, the winemaker at Glenora Wine Cellars in NY, and Megan Hereford from Scott Labs. As popular sparkling wine producers, Jerry and Steve will discuss their experiences with sparkling wine production throughout their winemaking careers. They will cover technical details pertaining to managing the second fermentation in the bottle for those attempting to produce a sparkling wine in the méthode champenoise style. Additionally, Steve will cover alternative methods for incorporating and maintaining carbonation in sparkling wines. Megan will also give a technical talk on how to stabilize sparkling wines, including the use of CMC in sparkling wines. This is a great session for those producers looking for practical tips on how to produce sparkling wine.

After a catered lunch, a panel of regional winemakers will share sparkling wines for all attendees to taste and discuss the processing techniques associated with those wines. This is an educationally-focused tasting so discussion is encouraged and expectorating all samples is mandatory.

While this program has a tasting component focused on sparkling wines, all of the techniques and information will be applicable to hard cider producers, as well.

Registration, the full agenda, location, and cost of the program can be found here: Sparkling Wine Production: Improving Bubblies in the Eastern U.S. We hope to see you there!

Hard Cider Production Resources

By: Denise M. Gardner

On January 13th, Penn State Extension hosted their first Hard Cider Production workshop at the Fruit Research and Extension Center (FREC) in Biglerville, PA. The day was filled with various speakers from New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia with perspectives from various Mid-Atlantic state hard cider industries. Topics were focused on the economics of hard cider production in the Mid-Atlantic, experiences with growing apples for hard cider production, how to produce hard cider, and orchard considerations for new hard cider apple variety growers.

Attendees of the 2015 Hard Cider Production workshop tasting a series of hard ciders from around the world.

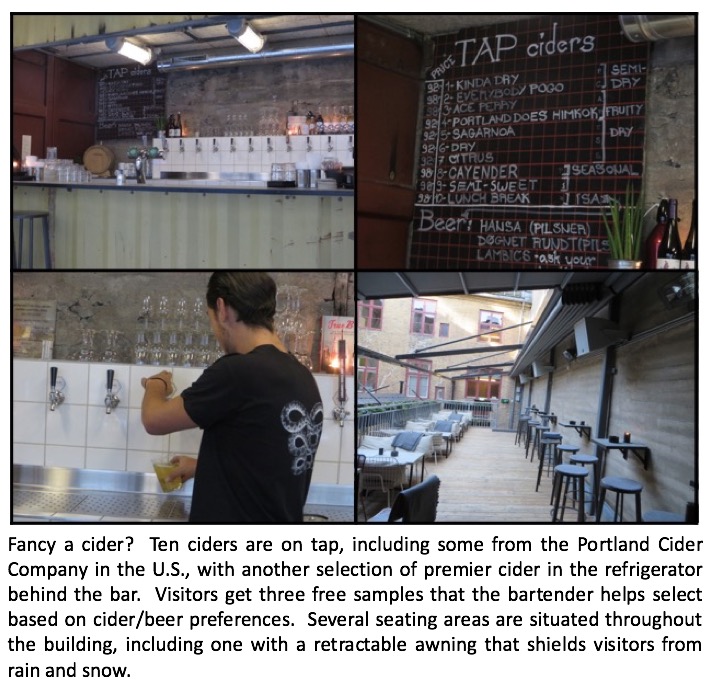

The program was incredibly successful and included a tasting of 8 different hard ciders, emphasizing the variation in styles and flavor currently available on the market:

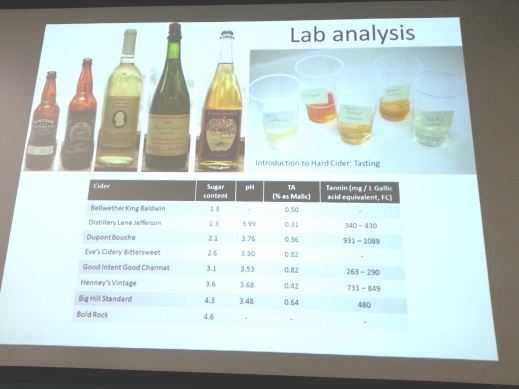

- Bellweather King Baldwin Hard Cider: With the least residual sugar, this light weight, well-balanced, dry cider had a lingering finish of citrus and apple flavors. For those getting into the industry, this is a good example of a well-made, clean hard cider.

- Distillary Lane Jefferson Hard Cider: One of the oakier ciders provided during the tasting, with prominent vanilla, oak and light apple flavors.

- Dupont Bouche Hard Cider: An amber color with a Brettanomyces aroma and flavor dominating the cider. Sweetness was well integrated and matched well with the barnyard flavors. A good example of Burgundian ciders.

- Eve’s Cidery Bittersweet Hard Cider: Floral with complementing cooked apple flavors, carbon dioxide was light and tasted less sweet than intended due to its tannic mouthfeel.

- Good Intent Good Charmat Hard Cider: A local, PA-produced cider with light petulance and butterscotch notes in addition to the apple juice aroma. Semi-sweet.

- Henney’s Vintage Hard Cider: This golden-yellow cider was the subject of much discussion. Flavors of Band-Aid and nailpolish dominated the nose, but had more apple flavor on the palate to supplement the acidic, acetic acid flavors.

- Big Hill Standard Hard Cider: Produced from a local cidery in PA, the light cooked apple favor of this cider was prominent with its sweetened mouthfeel.

- Bold Rock Hard Cider: A producer from New York that is producing a more commercial style of hard cider. This hard cider emphasized vanilla and light apple notes with a well-integrated and sweetened finish.

Analysis details of hard ciders tasted during the Penn State Extension Hard Cider Production 2015 workshop.

Attendees had many focused questions in various topic areas, which acknowledged the lack of resources available for the hard cider entrepreneur. The following lists a series of resources that were provided at this workshop that may be good starting points if you or your business is looking into hard cider production.

Consider Attending the Next Penn State Extension Hard Cider Production Workshop

This workshop focused on individuals that were thinking about or in the planning stages of building a business around hard cider production.

Text Books on Hard Cider Production

“Sweet and Hard Cider” by Annie Proulx and Lew Nichols

“The New Cider Maker’s Handbook” by Claude Jolicoeur

Online Publications for Apple Growers

“Antique Apples for Modern Orchards” by Ian Merwin, NY Fruit Quarterly 2009

“Growing Apples for Craft Ciders” by Ian Merwin (future issue of NY Fruit Quarterly)

WSU Bulletin on Cider Program in Mt. Vernan

Online Publications for Hard Cider Production

Hard Cider Production at Virginia Tech

Fermentation Protocols from Washington State University

Cider Juice Analysis Protocol from Washington State University

Scott Labs Hard Cider Fermentation Protocol

Cider Organizations and Conferences

US Association for Cider Makers

Online Information or Websites

Scott Labs Hard Cider Handbook

Penn State Extension Fruit Times

Old Time Cider (with additional resources)

Other Extension Programs Useful for the Hard Cider Producer

Cornell University: Cider & Perry Production – Principles and Practice Workshop

Penn State Extension – Sanitation Short Course

Warwickshire College Hard Cider Production Workshop

Northwest Agricultural Business Center Hard Cider & Perry Production Workshop