A Visit at the 17th Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference

By Dr. Helene Hopfer, Assistant Professor of Food Science, Department of Food Science

In late July of 2019, I was fortunate to be able to participate at the 17th AWITC in Adelaide, Australia. I was invited to speak about our sensory regionality study on commercial Riesling and Vidal blanc wines from Pennsylvania.

Last year, Dr. Kathy Kelley wrote about her sabbatical leave in Australia, and provided an excellent overview into Australia’s wine industry, therefore, this blog post will focus on the presentations and posters at the conference.

TheAustralian Wine Industry Technical Conference & Exhibition (AWITC)is happening every three years, organized by The Australian Wine Research Institute (AWRI)and the Australian Society of Viticulture & Oenology (ASVO). Combining plenary sessions, workshops, poster presentations and a large trade exhibition, the AWITC attracts a large audience (over 1,200 participants this year) primarily from the Australian wine industry. Over 4 days, every aspect of grape growing and wine making, from vineyard to grape vine to enology and wine consumers is covered, providing scientific stimulation and lots of discussion for the industry. Intended to present the latest research findings while at the same time being approachable and transferrable for industry members, the AWITC hosts a wide variety of speakers (academics, industry members, governmental speakers, as well as forward-thinking leaders from other industries). Proceedings and video webcasts of all talks will be made available online on the website, where also all past proceedings are made public. Lots of participants also live-tweeted from the conference, so many impressions can also be found on the official event twitter handle @The_AWITC.

The conference started out with a traditional welcome by a local Aboriginal leader from the Adelaide Plains people. Providing a Welcome to his people’s land and an invitation to learn and work collaboratively, his inspiring speech was a great kick-off to the event, followed by the official opening by the Australian Minister for Primary Industries and Regional Development.

In the first two sessions, the supply and demand for Australian wine and its future were evaluated. Following the official outlook from Wine Australia, Warren Randall provided a thought-provoking talk on China very soon becoming the number 1 wine-consuming nation in the world. Although individual wine consumption for Chinese is estimated to reach 1.6 L per person per year (compare to US consumers averaging to 3.1 L per person per year), the sheer number of Chinese middle-class consumers leads to an estimated additional need of 850 million L within the next 5 years. This additional need equates to 1.2 m tones of grape, about 71% of Australians total annual production! The Chinese will remain to be a net importer, particularly for quality wine – the question is though whether Australia will be able to satisfy this demand, especially with the severe drought many Australian grape-growing regions face.

The subsequent talks reiterated the importance of China as a major Australian wine importer as well as for Australian wine tourism: Brent Hill from the South Australian Tourism Commission presented compelling research showing that wine tourism improves brand recall and sales, independent of winery size. For example, international marketing campaigns in combination with direct flights to Adelaide led to tripling visits from China to wineries in South Australia. Wine tourism also aligns nicely with consumers’ demands for personalized products that align with their values. Health and Well-being are driving consumer preferences and will continue to do so, as presented by Shane Tremble from the Endeavor Drinks Group, a major alcoholic beverage retailer in Australia.

The afternoon session was dedicated to diversity, equity, and inclusivity in the wine industry. Our own unconscious biases create barriers to enter the wine industry, especially for talents from underrepresented groups. Diversity, equity, and inclusivity is not just about social justice, but is a real business loss, especially as the wine consumer base becomes more and more diverse. How can we make sure to meet the needs of our consumers if we don’t really understand them and their needs?

A large portion of the meeting was dedicated to different aspects of climate change and how the wine industry will be able to continue doing business. A representative from a major insurance company presented on her company’s strategy to climate change, and managing risks associated with a changing climate – from special loans for businesses to lower their carbon footprint and greenhouse emissions to ways to manage physical risks such as flooding and bush fires, this presentation was eye-opening. Tools already available for growers, such as high-resolution weather data, provide action-able data for e.g., harvesting or irrigation. Clonal selection, vine training systems and better suited varieties and rootstocks are another tool in the toolbox to adapt to climate change, particularly to higher temperatures and increased incidences of drought, as demonstrated by Dr. Cornelis van Leeuwen from Bordeaux Sciences Agro.

Ending with the conference’s gala dinner, this first day proved to be full of insights and what the future may bring.

The next day started off with the fresh science session, including research on how changing climate will also change insect and disease pressure: Using the example of sooty mold and scale insects, Dr. Paul Cooper presented data and models that show how warmer temperatures will influence occurrence of scale insects and subsequent sooty mold. Similar scenarios could become more prevalent in PA as well, as for example late harvest insect problems could appear at an earlier stage during berry ripening (see also this blog post by Jody Timmer).

On the enology-side, several presentations were given to look at smoke-taint remediation of wines, alternatives to bentonite fining with grape seed powder, and the mechanisms underlying autolytic flavors in sparkling wines. A particular interesting, but also terrifying talk was given by Caroline Bartel from the AWRI on increasing SO2tolerance of Brettanomyces bruxellensis strains: Over the past 3 years, the AWRI has seen an increased number of Brettanomyces strains that show greater tolerance to SO2, some exceeding 1 mg/L molecular SO2!

Biosecurity is a big topic for Australian grape growers, as almost all vineyards are own-rooted, including some of the oldest productive vineyards in the world being over 100 years old! This history is however under threat, as phylloxera has arrived in Victoria and New South Walesa few years ago. Managing the biosecurity threats and best practices to protect vineyards from not just phylloxera but also grapevine viruses was the overarching theme of this session. Showing data from the Napa Valley, Dr. Monica Cooper from UC Extension highlighted the importance of clean plant material when it comes to managing grape vine diseases: in a newly planted vineyard, not enough certified disease-free material was available, and hastily organized vines, infected with red blotch virus, were planted alongside healthy vines. Within a few years, 100% of infected vines had to be removed to avoid spreading of the disease into other parts of the vineyard and adjacent vineyards.

The last talk in the session was given by Dr. Antonio R. Grace from the Portuguese Association for Grapevine Diversity, who argues that clonal selection of grapevines may increase efficiency but decreases resilience, complexity, and diversity.

A particular interesting session was focusing on Agricultural Technology or AgTech – robots, drones, and intelligent robot swarms! A particular impressive and eye-opening talk was given by Andrew Bate from SwarmFarm, a farmer in Queensland who now develops and sells farming robots that oppose the trend for “bigger is better”: using a swarming approach (i.e., many smaller robots that operate autonomously for maximized efficiency and adaptability), he showcased how his approach is forward-thinking and sustainable, and fueled by his own experiences as a farmer and grower. If you can check out the videos on the website!

In a similar inspiring manner, Everard Edwards from the CSIRO presented on low-cost drones and sensors and how to use them in the vineyard to support decision-making: for example, a go-pro camera mounted on a small cart, driving along rows, could be used for yield estimation. The technology is already there, but we are still lacking the data algorithm to make sense out of the data.

The day was finished up with the flash poster research presentations of wine science students. From glycosylated flavor compounds locked up in grape skins, to vintage compression and the effect of very high temperatures (over 50°C/122°F) for a short time on grape berry development and tannin content, these talks showcased the breath of wine research in the various Australian research institutions. Following the evening’s theme, the next day’s fresh science included a talk on how to remediate reductive aromas in wines. Among the tested treatments (DAP addition post-inoculation, donor lees added after malo-lactic fermentation, copper addition, macro-oxygenation, and a combination of copper and macro-oxygenation) macro-oxygenation once a day of 1.5 L/min O2for 2 hours yielded the most promising results while copper addition increased the risk of reductive characters developing post-bottling. Similarly, how to easier measure total and free copper in wines and juice was the topic of Dr. Andrew Clark’s presentation. Working at the National Wine and Grape Industry Centerin Wagga Wagga, Dr. Clark developed an easy spectrophotometric method to accurately and precisely measure free and total copper in wines.

Last, a genetic study on Chardonnay revealed that the same clones (clone 95) shows a different number of mutations depending on where it is from.

Besides the many fascinating talks and the impressive trade show, the meeting also offered lots of opportunities to taste Australian wines. I was lucky enough to participate in a guided tasting of a type of fortified wines unique to Australia: Presented with an impressive number of Rutherglen Muscatwines of all ages and classifications, I was able to experience this special wine style, and must admit that I brought back some bottles of these “stickies”. Made from Muscat a Petit Grains Rouge grapes (literally Muscat with little red berries), very ripe grapes, accumulating very high sugar content, are fermented and fortified with grape spirit, then aged from 3 up to 20+ years in barrels. Wines undergo a solera blending, transferring wines slowly from barrel to barrel until bottling. Flavors range from floral, honey and orange peel all the way to viscous, toasted and caramel flavors. If you ever have the opportunity to taste such wines, I would strongly encourage you to do so – even if this is not your style of liking, it is for sure a worthwhile sensory experience!

Outside of the Conference I also had the chance to visit three remarkable places: The National Wine and Grape Industry Center (NWGIC) in Wagga Wagga, University of Adelaide and the Australian Wine Research Institute (AWRI) in Adelaide, and last, but not least, Penfold’s original winery in the Adelaide Hills for a special tour and tasting of the most expensive wine in Australia, the Grange.

Winemaking in Austria: An introduction and comments from an 8th generation winemaker

By Dr. Helene Hopfer

Since starting to work at Penn State last year, I am excited about all these local wines made of Austrian varieties. As a native Austrian, Grüner Veltliner, Zeigelt, and Blaufränkisch (called Lemburger in Germany and Kékfrankos in Hungary) and in particular, the (even) lesser known Rotgipfler, Zierfandler and St. Laurent, are near and dear to my heart (and my palate).

The more I learn about viticulture in Pennsylvania, the more similarities I discover: Similar to Pennsylvania, Austrian growers worry about late spring frosts, fungal pressure and fruit rot, wet summers, and damaging hail events [1]. So it is only fitting to provide some details and insight to Austrian winegrowing and winemaking through this blog post.

Located in the heart of Middle Europe, the Austrian climate is influenced by a continental Pannonian climate from the East, a moderate Atlantic climate from the West, cooler air from the north and an Illyrian Mediterranean climate from the South. Over the past decades, the number of very hot and dry summers is increasing, leading to more interest in irrigation systems, as on average the annual average temperature in Austrian wine growing areas increased between 0.3 to 1˚C since 1990 [2].

Austrian wine growers also see a move towards larger operations: Similar to other wine regions in Europe, the average vineyard area per producer is increasing, from 1.28 ha / 3.16 acres in 1987 to 3.22 ha / 7.96 acres per producer in 2015. Many very small producers who often run their operations besides full-time jobs are now selling grapes or leasing their vineyards to larger wineries. A similar trend is true for wineries [2].

Different to other countries where widely known varieties like Chardonnay or Pinot noir make up the majority of plantings, the most commonly planted grape varieties in Austria are the indigenous Grüner Veltiner (nearly 50% of all whites) and Zweigelt (42% of all reds), followed by the white Welschriesling and the red Blaufränkisch (Lemburger). Another interesting fact is that over 80% of all planted vines are 10 years or older, with 30% of all vines being more than 30+ years old [2].

The Austrian wine market is very small on a global scale, with just over 45,000 hectares / ~ 112,000 acres of planted and producing vineyards by around 14,000 producers nation-wide [2]. Nevertheless, Austrian wine exports are steadily increasing, particularly into countries outside of the European Union, such as the USA, Canada, and Hongkong, indicating a strong interest in this small wine-producing country. Austrian wines are considered high quality, attributable to one of the strictest wine law in the world, the result of the infamous wine scandal of 1985 [3]. Today, the law regulates enological treatments (e.g., chaptalization, deacidification, and blending), levels and definitions of wine quality (e.g., the “Qualitätswein” designation requires a federal evaluation of chemical and sensory compliance), and viticultural parameters such as maximum permitted yield of 9 tons/ha or 67.5 hL/ha and permitted grape cultivars (currently 36 different varieties) [4].

One of the leading figures in developing the now well-established Austrian wine law was Johann Stadlmann, then president of the Austrian Wine Growers’ Association. During his 5-year tenure starting in 1985 at the peak of the wine scandal, he made sure that the wine law could be implemented in every winery and ensured strict standards; Johann Stadlmann could be called the father of the Austrian ‘Weinwunder’ (=’wine miracle’), the conversion of Austria as a mass-producing wine country to one with an emphasis on high quality.

Weingut Stadlmann – an estate with a very long history

If you ever visit Austria, you most likely fly into Vienna, the country’s capital. Vienna is one of the few cities in the world that also has producing vineyards located within city limits. Just outside of the city limits to the South, lies another important wine region in Austria, the so-called ‘Thermenregion’, named after thermal springs in the region. The region has a long wine history, dating back to the ancient Romans, and later Burgundian monks in the Middle Ages. The region is characterized by hot summers and dry falls, with a continuous breeze that reduces fungal pressure. One of the leading producers within the region is the Weingut Stadlmann, dating back to 1778 and now run by the eighth generation, Bernhard Stadlmann. He is the latest in a line of highly skilled winemakers that combine innovation with a conservative approach. His grandfather, Johann Stadlmann (yes, the same guy of the Austrian wine law), was one of the first ones in Austria to use single vineyard designations on his wine labels. Bernhard’s father, Johann Stadlmann VII, a master in creating wines from varieties only grown in this region, and named ‘winemaker of the year’ in 1994, is known for his careful approach and is now working alongside his son, Bernhard. In 2007, Bernhard started the conversion of the family-owned vineyards to certified organic. The family cultivates some of the best vineyards in Austria, including the single vineyard designations ‘Mandel-Höh’, ‘Tagelsteiner’, ‘Igeln’, and ‘Höfen’, planted with the indigenous varieties Zierfandler and Rotgipfler only grown here in the region. Wines from these vineyards are among the very best Austria can offer!

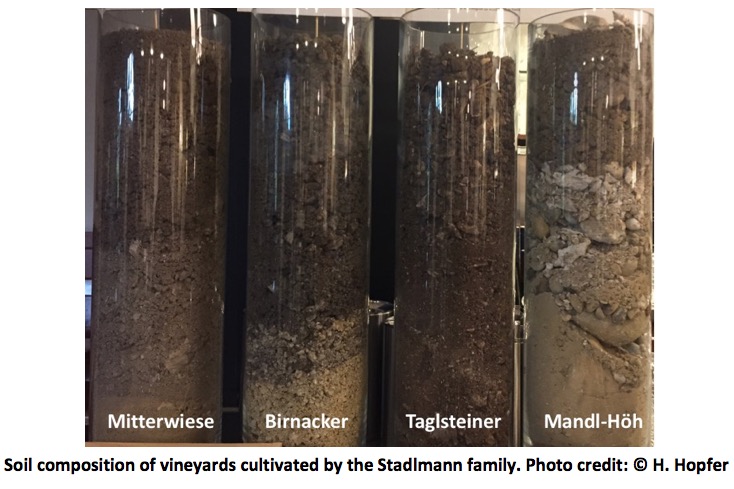

The vineyards cultivated by the Stadlmann family also differ quite dramatically in soil composition: While the ‘Mandel-Höh’ vineyard is highly permeable to water and nutrients, with lots of ‘Muschelkalk’ (limestone soil formed of fossilized mussels shells), is the ‘Taglsteiner’ vineyard characterized by more fertile and heavier ‘Braunerde’ soil, capable of retaining more water.

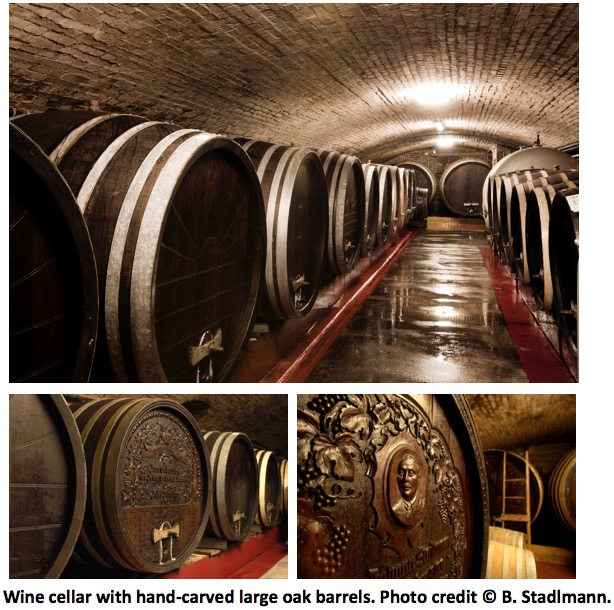

The long winemaking history becomes apparent once one steps into the wine cellar, full of large barrels, made of local oak: Some of these barrels have hand-carved fronts, depicting their vineyards and Johann Stadlmann senior. All of these barrels are in use, and part of the Stadlmann philosophy of combining tradition with innovation.

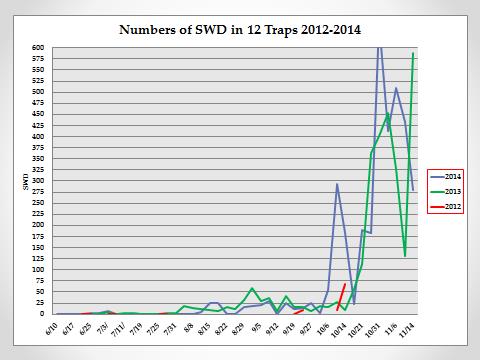

Another increasing threat is the spotted wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii, damaging ripening grape berries from véraison onwards. Bernhard sees some varieties more affected by Drosophila suzukii than others. There is intensive research on pest control, including shielding nets, fly traps, and insecticide strategies, and the Stadlmanns currently run experiments within their organic program: They blow finest rock flour (Kaolin and Dolomite rock) into the leaf canopy and fruit zone to create unfavorable conditions for different insects, including Drosophila, wasps, which pierce sweet berries, earwigs and Asian lady beetle, both leafing residuals causing off-flavors in the wine once they’re crushed. Drosophila suzukii was first discovered in Austria a few years ago and is also an issue in the US (see also Jody Timer’s blog post).

During a recent visit at the Stadlmann estate, I had the chance to chat with Bernhard about the challenges of Austrian winegrowing and winemaking. I was interested in a young winemaker’s perspective, especially as Bernhard has been trained all around the world, including Burgundy, Germany, and California. This year, spring frost in late April threatened vineyards in many winegrowing regions in Austria, requiring the use of straw bales and paraffin torches to produce protective and warming smoke. Luckily, not too much damage was done to the Stadlmann’s vineyards, however, it caused some sleepless nights for Bernhard and his family, and shows also the importance of developing effective spring frost prevention alternatives (see also Michela Centinari’s blog post).

We also talked quite a bit about wine quality: while the Austrian ‘Qualitätswein’ designation ensures basic chemical (e.g., ethanol content, titratable and volatile acidity, residual sugar, total and free SO2, malvidin-3-glucoside content (for reds), etc.) and sensory (i.e., wine defects like volatile acidity, Brettanomyces, atypical aging, mousiness and other microbial defects) quality, this only ensures a lower limit of quality. In the recent years, the Austrian governing bodies added another layer of wine quality, based on the Romanic system of regional typicity and origin: The so-called DAC (Districtus Austriae Controllatus) wines are quality wines typical for a region, made from varieties that are best suited for that region. DAC wine producers adhere to viticultural, enological, and marketing standards, with the goal to establish themselves as famous wines of origin (think Chablis, Cote de Nuits, Barolo, Rioja or Vouvray). As this is a relatively new system for Austria, we will see how successful these DAC regions will be. Their success will also depend on the regional producers, and how stringent they set the criteria for the DAC designation, as they have to walk a fine line between establishing a recognizable regional typical wine without losing individual character that each producer brings to their wines.

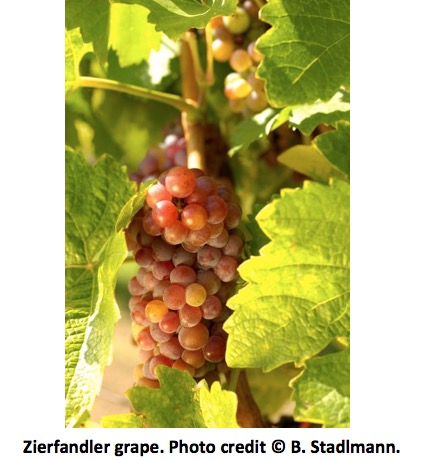

If you are interested in learning more about Austrian wines, and Bernhard and his family’s wines, they were recently highlighted in a couple of US wine publications, including a great podcast episode on ‘I’ll drink to that!’ and an article in the SOMM journal about Zierfandler. Zierfandler is one of Stadlmann’s signature varieties, indigenous to the region, but tricky to grow, as it requires long and dry ripening periods and has a very thin skin, prone to botrytis. However, when done well (like the Stadlmanns do), it produces extraordinary wines with fruity, floral, and sometimes nutty notes that have a long aging potential. If you are able to get your hand on these Zierfandler wines get them while you can!

Last, a big Thank You to Bernhard Stadlmann for his help with this blog post: He took time out of his super busy harvest schedule to show me around, never getting tired of answering my questions. He also graciously provided all but one of the pictures.

References

[1] Huber K (2017) Durchschnittliche Weinernte 2017 erwartet. LKOnline. Available at (in German): https://noe.lko.at/weinbau+2500++2455141

[2] Austrian Wine Marketing Board (2017) Austrian Wine Statistics Report 2015. Available at (in German): http://www.austrianwine.com/facts-figures/austrian-wine-statistics-report/

[3] New York Times (1985) Austria’s Wine Laws Tightened in Scandal. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/1985/08/30/world/austria-s-wine-laws-tightened-in-scandal.html

[4] Austrian Wine (2017) Wine Law. Available at: http://www.austrianwine.com/our-wine/wine-law/

Will The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Be A Problem In Wine And Juice?

By: Jody Timer, Research Technologist

The brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB), Halyomorpha halys (Stal) is an invasive species that has become a major pest in the eastern United States. This pest originally became a sizable problem in Mid-Atlantic vineyards, including southwestern Pennsylvania, during the 2010 growing season and continues to be a large-scale problem. The Lake Erie grape belt is the largest Concord grape growing region in the world. The recent appearance of the brown marmorated stink bug in Lake Erie vineyards has the potential to become problematic. After the mild winter of 2015-2016, the numbers of BMSB in this area began to increase rapidly. This winter, frequent complaints have been received from homeowner concerning the presence of BMSB in their houses.

BMSB have been found in both grape foliage and grape clusters; they seek the moisture, sugar, and warmth on the inside the clusters (especially overnight) and they often migrate to the cluster’s interior close to harvest. This makes the possibility of BMSB inside the cluster very likely when these grapes are mechanically harvested and transported to the processor.

All BMSB life stages (5 instars) have been observed in vineyards indicating that grapes are a suitable crop for BMSB development, and all stages have been found to cause direct damage to grapes (Bernon 2004). At the Lake Erie Grape Laboratory, we have maintained an adult BMSB colony on a diet of Concord grapes with no apparent development problems. It has also been estimated that the presence of 5 BMSB per grape cluster may lead to 37% loss in grape yield as a result of BMSB damage (Smith et al. 2014). With the yearly increase of numbers of BMSB in the Pennsylvania vineyards, the possibility of BMSB tainting the juice produced in this area is becoming a primary concern to processors, growers, marketers, and consumers.

Life stags of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug. Photo from: http://www.mda.state.mn.us/plants/insects/stinkbug.aspx

Insects produce small, volatile molecules that may be imparted to juice and wine during crush. Humans are able to detect these molecules at extremely low concentrations. For example, 2-isopropyl-3-methoxypyrazine (IPMP) from Multicolored ladybeetles (ladybug taint) is detectable at 0.30 ng/L concentrations in Concord grape juice (Pickering et al. 2008). BMSB have a distinctive odor which has been described as green, cilantro-like, which may or may not be off-putting within grape juice aroma. BMSBs produce taint associated compounds as allomones, alarm pheromones, aggregation pheromones, and kairomones. These compounds are mainly released from the dorsal abdominal glands in nymphs and paired metathoracic glands in adults (Baldwin et al. 2014). When BMSBs are crushed along with grape clusters, release of these compounds could potentially taint in the juice.

Multidimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry (MDGC-MS) analysis of stressed BMSB, adults and nymphs, has been used to identify more than 39 compounds. The volatile compounds in the taint are tridecane, dodecane, trans-2-decenal and trans-2-undecen-1-ol. Tridecane and trans-2-decenal together constitute at least 70% of BMSB taint (Baldwin et al. 2014; Solomon 2013). Trans-2-decenal, is the major irritant and is believed to be responsible for the potent stink odor from BMSB. However, being an extremely unstable compound it can easily break down, and its degradation products lack the distinctive BMSB odor (Baldwin et al. 2014). When trans-2-decenal was added to red wine (Pinot Noir) the morning of testing, the detection threshold was in the low microgram per liter (ug/L) range (Mohekar et al 2015). However, because trans-2-decenal is unstable, this may not reflect what happens when juice is processed and stored. Joe Fiola from University of Maryland, reported that while 5-10 BMSB per 25 pound lug of white grapes imparted a perceptible taint in raw juice for up to four months in some cases, the taint was not perceptible in the wine after fermentation (Fiola 2011). Mohekar and colleagues, from Oregon State, reported that trans-2-decenal, has a detection threshold in the ug/L range in Pinot Noir wines, and was able to be detected by tasters (Mohekar et al 2016).

Informal sensory testing with the on-site staff was performed at the Lake Erie Regional Grape Research laboratory. Small batches of grape juice were produced using a residential Kitchen Aid® juicer, and increasing numbers of BMSB were added. Batches of juice containing the equivalent of 0, 2, 10, and 25 BMSB per lug (~35 lbs. of Concord grapes) were tasted raw and after high-temperature, short-time pasteurization (HTST) by five staff members. In blinded triangle tests (2 blanks and 1 spiked sample), 5 of 5 individuals correctly identify the spiked sample of the 25 BMSB/lug juice (both raw and pasteurized); for the 10 BMSB sample, 4 of 5 correctly identified the spike in raw juice, and 5 of 5 identified the spiked sample for the pasteurized juice. The following month the pasteurized juice was re-tasted by 10 individuals and similar results were obtained. These tests suggest 25 BMSB/lug are sufficient to induce a perceivable flavor change in Concord grape juice. Following this testing, a set of samples were processed at the Food Science laboratory of Penn State, using industrially relevant methods (equivalent to Welch’s Corporation processing techniques), to assess if the odor-causing compounds secreted by BMSB were stable enough to transfer through the juicing, processing, pasteurization, and storing of grape juice and therefore cause it to be rejected by consumers. Large scale sensory tests were then run with regular grape juice consumers to quantify rejection thresholds for BMSB-spiked, processed grape juice.

Grape clusters, with varying amounts of BMSB (0, 4, 8, 16, 24, and 32 BMSB, per 35 lbs), were crushed and destemmed; the juice was pasteurized, clarified and blended. Following storage for 8 weeks (2 months after initial processing), sensory testing was performed with grape juice consumers in the controlled sensory testing facility to determine rejection thresholds for different levels of BMSB. Sensory testing was then repeated 8 weeks later (4 months after initial processing).

Despite the use of BMSB levels that clearly caused a noticeable change in the flavor of processed juice in pilot testing, we were unable to find a level of BMSB that caused rejection in consumers following processing and storage at either time point.

As the area’s BMSB population increases, this research will be notably important for processor to determine threshold levels at harvest. This research suggest that taint from BMSB at high but realistic doses for the Lake Erie grape-growing region will not influence consumer acceptability. Conversely however, our results may not generalize to smaller producers in the area who make grape juice using exclusively from Concord grapes. Typically, this juice is sold as fresh juice with a limited shelf life. These smaller growers and producers should be aware of the possibility of taint in their juice especially with the increasing numbers of BMSB in the region. Pre-harvest scouting for BMSB should be conducted to determine if a pre-harvest BMSB insecticide spray should be applied.

References:

Baldwin, R.L. IV, A. Zhang, S.W. Fultz, S. Abubeker, C. Harris, E.E. Connor, and D.L. Van Hekken (2014) Hot topic: Brown marmorated stink bug odor compounds do not transfer into milk by feeding bug-contaminated corn silage to lactating dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 97. 1877-1884.

Bernon, G. (2004) Biology of Halyomorpha halys, the brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) Final Report—USDA APHIS CPHST Project T3P01. USDA APHIS.

Fiola, J.A. (2011) Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (BMSB) Part 3-Fruit Damage and Juice/Wine Taint. Timely Viticulture. University of Maryland extension,

http://www.grapesand fruit.umd.edu. Accessed October, 2016

Mohekar. P. (2016) Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (BMSB), Halyomorpha halys Taint in Wine: Impact on Wine Sensory, Effect of Wine-processing and Management Techniques. Dissertation Oregon State University

Mohekar, P., Tomasino, E., Wiman, N.G., (2015) Defining defensive secretions of brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys. Presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America, Minneapolis, MN

Pfeiffer, D. G., T. C. Leskey and H. J. Burrack, (2012) Threatening the harvest: The threat from three invasive insects in late season vineyards, pp. 449-474. In N. J. Bostanian,

Pfeiffer, D., J. Fiola, B. Lamp, K. Rane, A. Nielsen, D. Polk, B. Petty, D. Ward, M. Saunders, J. Timer, C. Hedstrom, P. Mohekar, N. Wiman, E. Tomasino and V. Walton, (2013) BMSB in Vineyards and Wines. www.stopbmsb.org/stopBMSB/assets/File/Research/BMSB…/Vineyards-Vaughn.pd . Accessed September 2016

Pickering, G.J., Karthik, A., Inglis, D., Sears, M. and K. Ker, (2008). Detection Thresholds for 2-Isopropyl-3-Methoxypyrazine in Concord and Niagara Grape Juice. Journal of Food Science, 73 (6): S262-S266.

Prescott, J., Hayes, J. E., & Byrnes, N. K. (2014). Sensory Science. In N. K. V. Alfen (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems (pp. 80-101). San Diego: Elsevier.

Smith, J.R., Hesler, S.P., and Loeb, G.M., (2014) Potential Impact of Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) on Grape Production in the Finger Lakes Region of New York. J. Entomol. Sci. 49, 290–303. doi:10.18474/0749-8004-49.3.290

Solomon, D., D. Dutcher, and T. Raymond, (2013) Characterization of Halyomorpha halys (brown marmorated stink bug) biogenic volatile organic compound emissions and their role in secondary organic aerosol formation. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1995 63, 1264–1269.

Welch’s Corporation, www.Welch’s.com Accessed August 2016.

2017 PA Research Symposium Provides Research-Based Practicality for PA Grape Growers and Winemakers

By: Denise M. Gardner

The Pennsylvania Wine Marketing and Research Board (PA WMRB) annually awards researchers and graduate students grants to explore pertinent topics to the Pennsylvania wine industry. For the 2016 – 2017 fiscal year, four projects were awarded industry-funded grants. Results from these four projects will be presented at the 2017 Symposium, co-hosted by the PA WMRB, Penn State Extension, and the Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA).

Registration is being organized through the PWA, and can be found here:

This year’s Symposium, held on Wednesday, March 29th at the Nittany Lion Inn (University Park, PA) will only run in the morning and is packed with 5 sessions of information pertinent to both the enology and viticulture fields in Pennsylvania. At the close of the Symposium a lunch will be provided for all attendees.

Guest Speaker has Enology and Tannin Focus

The WMRB Symposium key guest speaker is Dr. Catherine Peyrot des Gachons, Winemaker Consultant at Chouette Collective. Dr. Peyrot des Gachons has assisted Pennsylvania wineries with enhancing their quality production for several years. She will be speaking towards her tannin and wine aroma matrix research that she has been working on at the Viticulture and Enology Department through the University of Montpellier (France).

Dr. Catherine des Gachons, winemaker consultant, will be the key guest speaker at the 2017 PA Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium.

Tannins: Modulation of wine structure and aroma

From environmental factors on tannin biosynthesis to human interventions to modulate tannin content in wine what do we know and what can we do to modulate wine structure. Can this tannin content impact wine aroma? The presentation will focus on few main points of interest with practical applications.

Enology-Focused Presentations

An additional enology-based presentation will feature Laurel Vernarelli, a graduate student in Dr. Ryan Elias’s lab within the Penn State Department of Food Science. Laurel’s presentation will be an extension from Dr. Gal Kreitman’s work that was presented last year on predicting reductive off-odors in wines. Laurel will explore the use of copper fining in wine production and the potential impact it may have on wine quality. Given the prevalence of reductive off-odors, including hydrogen sulfide, and heavy reliance on copper fining, this topic should be of considerable interest to most wineries.

Laurel Vernarelli will give an update on treating reductive and hydrogen sulfide aromas/flavors with copper sulfate at the 2017 PA Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium.

Reconsidering copper fining in wine

This presentation will include a brief overview of copper fining, along with the impact of reductive thiols and recent findings describing the effect that copper has in wine. A method for using immobilized copper materials in place of copper fining is described. Depending on the result obtained, winemakers can make informed decisions for use of alternative fining techniques when dealing with reductive issues.

Viticulture-Focused Presentations

For those with an interest in viticulture, this year’s program promises to deliver some key updates. Bryan Hed, Research Technologist for the Department of Plant Pathology, will present his annual updates regarding disease management for Pennsylvania vineyards. For those that are frequent blog followers, Bryan is a lead contributor to the important seasonal reviews. These tend to be very popular posts for growers and his presentations are always informative and practical. If you missed the 2016 seasonal reviews, you can find them here:

- Looking back at the 2016 season

- Late summer/early fall disease control, 2016

- 2016 Post-bloom disease management review

- 2016 Pre-bloom disease management review

Bryan’s talk at this year’s Symposium is a continued study with results collected over 2 years, which helps initiate trends and suggestions useful towards growers.

Bryan Hed from Penn State University will review current disease management techniques for the vineyard at the 2017 PA Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium.

Updates on Grape Disease Management Research

Fruit zone leaf removal can be a very beneficial practice in the management of harvest season bunch rot. Bryan will start his presentation by briefly reviewing the pros and cons of different timings of this practice. In addition, leaf removal by hand is very expensive and labor intensive, and with the increasing scarcity and rising cost of hand labor, mechanization is crucial to increasing cost effectiveness and adoption of this practice, no matter what the timing. Bryan will follow up with an in depth discussion of the progress made toward mechanizing an early, pre-bloom leaf removal and comparing its effectiveness over a variety of wine grape cultivars and training systems during the past two seasons.

Maria Smith, Ph.D. candidate in Dr. Michela Centinari’s lab, will discuss her research regarding early leaf removal in Gruner Veltliner vines. Maria and Dr. Centinari have previously written a blog post pertaining to leaf removal strategies for Mid-Atlantic vineyards, which could act as an excellent primer to Maria’s presentation in March. Her presentation will deliver two-years (2015, 2016) of data regarding the effects of early leaf removal and cluster thinning techniques on Gruner Veltliner vines.

Penn State Plant Science Ph.D. Candidate, Maria Smith, will discuss her research on early leaf removal and cluster thinning techniques for Gruner Veltliner at the 2017 PA Wine Marketing and Research Board Symposium.

Vine response and management costs of early leaf removal for yield regulation in V. vinifera L. Gruner Veltliner

Early leaf removal (ELR) and cluster thinning (CT) were applied and compared for yield regulation in Grüner Veltliner over the 2015 and 2016 growing seasons. Early leaf removal was performed at two different times, trace-bloom and fruit-set. We compared the effects of ELR and CT on grape quality, vine health, and economic costs to un-thinned vines.

Finally, Dr. Michela Centinari will follow up with further results regarding sprayable products to reduce frost damage in wine grape vineyards. Michela’s frost research has been a prominent topic at previous Symposiums, and is often featured here on the blog site. While the updated results that will be presented at the 2017 Symposium have not yet been reported through Penn State Extension, please see some of her past blog posts pertaining to frost control and freeze damage in the vineyard:

- Understanding and Preventing Spring Frost/Freeze Damage – Spring 2016 Updates | Wine & Grapes U.

- Updates on Freeze Injury in Grapevines

- Evaluate cost-effective methods to decrease crop losses due to frost injury

- An update to studies on frost injury, by Maria Smith

Dr. Michela Centinari will discuss her current research findings pertaining to frost protection in the vineyard at the 2017 PA Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium.

Spray-on materials: can they reduce frost damage to grapevines?

Dr. Centinari will present results of studies conducted to test the efficacy of sprayable products as a low-cost frost protection strategy. Two materials Potassium-Dextrose-Lac (KDL) and a seaweed extract of Ascophyllum nodosum, were tested for their cryo-protective activity using a controlled-freezing technique on several grapevine cultivars.

We hope to see you there!

Tasting Chambourcin: Part I

By: Denise M. Gardner

Note: Sensory descriptions of wines produced by the grape variety, Chambourcin, are based on individual observations, tastings, and a collection of notes obtained through various Chambourcin tastings including many different individuals.

At the Central Pennsylvania regional winery meeting held at Brookmere Winery, attendees and I had the opportunity to taste through a series of Pennsylvania-grown and produced Chambourcin wines. This was actually one of the first all-Chambourcin wine flights that I have been able to taste, and I was quite encouraged by what I was tasting in the glass. Paula Vigna, writer for The Wine Classroom via Penn Live, has since written an article on the tasting titled, “Chambourcin’s ceiling: Maybe higher than originally thought.”

Chambourcin: A Description

Chambourcin is a French-American hybrid wine grape variety that was bred by crossing Seyve-Villard 12-417 (Seibel 6468 x Subéreux) with Chancellor*, commercialized in 1963 (Robinson et al. 2012). Despite Chambourcin’s vigor and relative tolerance to disease pressure in humid climates, anecdotally the wine does often appear preferred by many Vitis vinifera winemakers.

As a wine, Chambourcin’s strength is its vibrant red color and supple, soft mouthfeel due it is relatively lack of course tannin on the palate. These features often make it a valuable red wine blending possibility, especially considering the relative consistency of obtaining Chambourcin fruit every vintage. However, the smoothness of the wine often is a frustration by many eastern winemakers looking for more depth and [tannin-related] mouthfeel in their red wines. When coupled with Chambourcin’s notorious ability to retain acidity, often above 7 g/L of tartaric acid (depending on where and how it is grown), the lack of perceived tannin can make the wine taste relatively thin and acidic.

The acidity associated with the Chambourcin grape variety often appears retained when grown in cooler climates. For example, in Pennsylvania, Chambourcin produced in North East, PA (Erie County) often has relatively higher TAs compared to Chambourcin grown in southeastern, PA (e.g., Berks County). From a grape growing perspective, all winemakers should expect this phenomenon. However, Chambourcin can retain a higher acidity even when grown in the warmer southern parts of Pennsylvania. Based on observation, the variety seems to maintain its acidity when it is not thoroughly crop thinned. As Chambourcin is an incredibly vigorous variety, and as you will see from the tasting, producers hoping to drop the acidity often crop thin grape clusters while on the vine.

When looking at the tannic composition of Chambourcin, it is likely that much of the tannin content associated with Chambourcin is lost during primary fermentation. Dr. Gavin Sacks at Cornell University is studying this situation associated with many hybrid wine fermentations. As Dr. Sacks discussed at the 2016 Pennsylvania Wine Marketing & Research Board (PA WMRB) Symposium in March, tannins come from 3 different components of the grape: the stems, the skin, and the grape seeds. During the fermentation process, anthocyanins (red pigments) and skin tannin is extracted quickly, usually before the product starts to ferment. Seed tannin is extracted more slowly, typically throughout primary fermentation and extended maceration processes. Dr. Sacks’ lab (Springer and Sacks, 2014) and previous research (Harbertson et al. 2008) have shown, grapes produced outside of the western U.S. generally have lower concentrations of tannin available in the grape. While available tannin in the grapes does not necessarily correlate with tannin concentrations in the finished wine, many eastern U.S. winemakers will add exogenous tannin pre-fermentation, during fermentation, and/or post-fermentation to help improve mouthfeel and potentially increase substrate availability for color stability reactions. However, even with exogenous tannin additions, Dr. Sacks has found that many of the tannins associated with hybrid fermentations end up lost during the fermentation process due to protein-tannin binding complexes that pull tannins out of the wine. The higher protein concentration associated with the hybrid grapes has been linked to disease resistance mechanisms that the varieties were originally bred for, and is more thoroughly explained in Dr. Anna Katharine Mansfield’s recent Wines & Vines article, “A Few Truths About Phenolics.”

Additionally, Chambourcin has been noted to have a relatively neutral red wine flavor, lacking a concentrated pop of fruit and using non-descript aromatic or flavor descriptors like: red cherries, red fruit, red berries, stemmy, herbal, or even millipedes. And yes, I have heard one or two consumers actually reference a millipede aroma when tasting Chambourcin.

Tasting Chambourcin Produced in PA

Figure 1: Flight of Chambourcin Wines tasted at the June 2016 Central PA Regional Wine Meeting, hosted by Brookmere Winery. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

The official flight (Figure 1) of Chambourcin wines that I had put together included:

- Galen Glen Winery 2014 Stone Cellar Chambourcin

- Penns Woods Winery 2014 Chambourcin Reserve

- Vynecrest Winery 2014 Chambourcin

- Pinnacle Ridge Winery 2013 Chambourcin Researve

- Allegro Winery 2012 Chambourcin

Additionally, Brookmere Winery, Armstrong Valley Winery, and Caret Cellars (Virginia) added Chambourcin wines to taste. The formal wine tasting turned out to be quite a unique experience.

I saw a few over-arching sensory themes within these wines:

- Reduced acidity: While I did not personally measure the pH and TA for these wines, the perception of acidity was not as obvious, overly perceptible, or offensive.

- Soft, supple mouthfeel: Even with a couple of the wines that were perceived as “more tannic,” these wines were soft and easy-drinking.

- Use of oak barrels: Many of the producers were opting for some production in actual oak barrels as opposed to using oak alternatives. Type of oak ranged from French, American, and Hungarian.

- Higher alcohols: Alcohol concentrations for these wines ranged from 13-14%, likely due to extended hang time in the vineyard, allowing for an increase in sugar accumulation.

- Two emerging aromatic profiles: A couple of the wines were very fruit-forward and fruitier than what is normally expected from Chambourcin. The other wines were less fruit-forward, however, they did retain a fair amount of red fruit aromatics in addition to the complex aroma nuances: earthiness, tobacco, toasted oak, vanilla, and tobacco. Many tasters commented on the general concentration of aromatic nuance associated with many of the wines we tasted.

In general, the relative depth, cleanness, and fruit expression of these wines was impressive. Perhaps this tasting clearly indicated that although many winemakers struggle with finding the “right fit” or style for their Chambourcin, the level of quality associated with the wine has definitely improved within the last 5 years. At the very least, the level of quality associated with this flight of wines was encouraging for hybrid red wine producers.

Additionally, Brookmere Winery provided a real treat from their cellar library: a 1998 Chambourcin produced by Brookmere Winery (Figure 2) when Don Chapman owned the winery. If you appreciate older wines, then this Chambourcin would truly impress you. Not only did it express the “old wine” honey-floral character loved by many wine enthusiasts, but the red fruit aromas and flavors were still boldly expressed in the wine. The color was intense and dynamically red, and there was a fine perception of firm tannins on the palate. Overall, the tasting of this wine gave me the perception that not only did this wine still have plenty of room to continue aging in the cellar, but that Chambourcin, as a wine varietal, had positive potential for aging for more than 10 years.

Given that most of this post is based on my own experiences, perceptions, and information gathered from growers and producers pertaining to Chambourcin, I would welcome any additional experiences with the variety (as a grape or as a wine) in the comments section.

While this post has documented Chambourcin as a grape variety and a small snap shot of sensory perceptions from a handful of producers in Pennsylvania, next week’s post will focus on production techniques to improve the quality Chambourcin red wines.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

For more information on upcoming regional meetings and the types of tastings to be held at those FREE events, please visit: http://extension.psu.edu/food/enology/events

- Northwestern PA (Erie County) – Individual Site Visits

- Southwestern PA (La Casa Narcisi Winery) – Talk on High Potassium Winemaking

- Southeastern PA (Vineyard at Grandview) on Thursday, July 28th – Berry Sensory Training hosted by Lallemand, with international wine consultant Dominique Deltei (Must register with Denise (dxg241@psu.edu) as space is limited to 15 people.)

Resources

Harbertson, J.F., R.E. Hodgins, L.N. Thurston, L.J. Schaffer, M.S. Reid, J.L. Landon, C.F. Ross, and D.O. Adams. 2008. Variability of tannin concentration in red wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 59:210-214.

Mansfield, A.K. January 2015. A few truths about phenolics. Wines & Vines.

Robinson, J., J. Harding, and J. Vouillamoz. 2012. “Chambourcin.” pg. 218-219. Wine Grapes. ISBN: 978-0-06-220636-7

Springer, L.F. and G.L. Sacks. 2014. Protein-precipitable tannin in wines from Vitis vinifera and interspecific hybrid grapes (Vitis ssp.): differences in concentration, extractability, and cell wall binding. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62(30):7515-7523.

*Authors Note: Since the publication of this article, a few growers and grape breeders have alluded to the improperly reported parentage of Chambourcin. While it is generally reported and cited as such, it is understood among some wine grape experts that Chancellor is not likely a parent to Chambourcin. For more information on determining parentage of given grape cultivars, please refer to: http://www.vivc.de and search the cultivar name of interest.

Regional Winery Meetings Scheduled for Pennsylvania Wineries in Summer 2016

By: Denise M. Gardner

Each calendar year, Penn State Extension works with the state wine industry to schedule “regional” meetings with local producers.

Regional meetings are kindly and financially supported by the PA Wine Marketing and Research (WMRB) Board and Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA), as part of the annual operating expenses that are granted to the Penn State Extension Enology position each fiscal year. The financial support is, in part, contributed by each Pennsylvania winery in the annual assessment on the gallons of wine produced across the state, which are submitted to the PA WMRB. It is this funding mechanism that makes these visitations possible on an annual basis, and all Pennsylvania wineries are encouraged to attend.

These regional visitations by the Extension Enologist were designed to be convenient for local industry members in terms of location. While industry members, or perspective industry members are welcome to attend any of the meetings, the purpose of these meetings is for me to get out into various parts of the state while making traveling a bit more convenient for industry members.

Regional meetings are free for industry members or prospective members to attend.

All regional meetings are hosted at a local winery, and meeting locations are listed below and on the Penn State Extension Enology website.

Each region organizes their regional visits differently, and they are designed to be beneficial for that region of industry members.

Regional meetings all have a unique structure. Many are only a few hours long, offer a production tour of a local winery, and many include a tasting. In the past, regional meetings have included anything from question and answer sessions on a production tour:

Denise Gardner discusses winemaking with Sharon Klay from Christian Klay Winery. Photo from: Mark Chien

To tasting bench trials created by some of the local wineries:

To hosting benchmark tastings on specific wine varieties:

To holding a short educational program on a topic of specific interest to that region.

Dr. Kathy Kelley presents her research on tasting room design at a regional meeting in Erie County. Photo from: Denise Gardner

Additionally, these visitations by the Extension Enologist offer several benefits to the local industry, including:

- meet with existing producers to discuss potential problems or challenges within the winery,

- visit with potentially new or new producers within the wine community,

- introduce new producers to existing operations to enhance networking and collaboration across the state,

- answer questions pertaining to wine production and quality, and

- review Penn State research updates pertinent to the wine community.

The tentative agendas for each regional meeting, in addition to their scheduled date, for 2016 are listed below.

- Central PA: Thursday, June 16th, hosted at Brookmere Winery

The program at Brookmere will include a production tour with a question and answer period by all attendees. Additionally, Denise will conduct an educational tasting on local Chambourcin wines produced across Pennsylvania. This was created by request from the regional producers in order to get a better idea of how Chambourcin tastes throughout the state.

- Northwestern PA (Erie County): Wednesday, August 3rd – To schedule a winery visit by Denise, please contact Andy Muza to get on the schedule.

This regional visit will follow the day after the “Stabilize Your Wine – Filtration, SO2, and Potassium Sorbate” workshop hosted by Cornell and Penn State Extension at the CLEREL Station in Portland, NY. This workshop requires pre-registration (see the attached link), and anyone is welcome to attend with paid registration.

On August 3rd, Denise will visit individual wineries to discuss winery-specific problems or to keep Denise current on what is happening in the winery. To schedule an appointment with Denise, please contact Andy Muza in the Erie County Extension Office.

- Southwestern PA: Thursday, August 4th, hosted at La Casa Narcisi Winery

The southwestern regional meeting will be held at La Casa Narcisi Winery and include a production tour. Denise will host a small educational session on high potassium winemaking with a tasting of the high potassium wines (i.e., Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon) that were produced by Penn State during the 2015 harvest. Wineries are welcome to bring their own wines for feedback and welcome to stay through lunch, which can be purchased at the restaurant on site at La Casa Narcisi.

- Northeastern PA: Date and location TBD, but please reserve August 30th or 31st on your calendars

Currently, the date and final agenda for the northeastern part of the state is being discussed. But, please continue to check the “PSU Extension V&E News” listserv and Extension Enology website for updates.

More information, and updates, on each regional visit can be found at: http://extension.psu.edu/food/enology/events. Pre-registration is NOT required for anyone to attend regional meetings.

While there is not a Southeastern PA regional meeting currently scheduled, there are several events hosted in the southeastern section of PA that are conveniently located for those regional wineries. Wine Trails in the southeastern quadrant of PA are encouraged to contact Denise for specific visitations.

The most current workshop on the calendar includes the Sensory Defects for Fermented Beverages and Distilled Spirits workshop, held on June 9th, which will be hosted in Collegeville, PA (Montgomery County). Registration for this workshop is required, and details for the program can be found at the above link.

As is the past, the Penn State Extension Enologist acts as a resource for Pennsylvania wineries when production problems or questions arise. You can find contact information In addition to the list of educational programming designed for the local industry, Penn State Extension is filled with:

- Online resources via Penn State Extension’s website

- The “Wine & Grapes U.” blog site, which includes a yearlong calendar of local/regional/national events and local sales and job opportunities.

- Annual workshops including the Wine Quality Improvement (WQI) Short Course held every January, the upcoming Sensory Defects for Fermented Beverages and Distilled Spirits workshop, the PA Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium, and many additional workshops that cover a multitude of topics. Previous workshop topics covered: micrbiological techniques for wine production, the use of sulfur dioxide in the winery, pre-harvest preparation, benchmark wine tastings, blending, and more!

- Wine Made Easy Fact Sheets, which can now be found on the Extension website! These are quick print outs designed to help winemakers in the winery. Visit the link for all of the topics currently published.

- The weekly “Penn State Extension V&E News” listserv, distributed every Friday to keep industry members current on research, real-time issues in the vineyard and winery, and upcoming events pertinent to this industry.

Reflections: Winemaking at Penn State

By: Denise M. Gardner

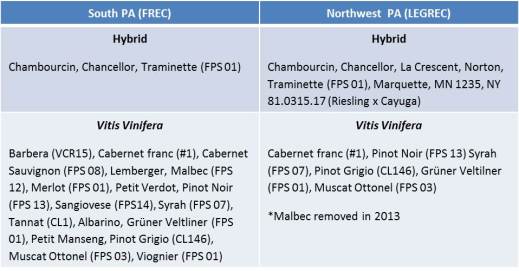

I can officially say that I have now been involved with 5 harvests here at Penn State, with my first harvest in 2011. Returning to Pennsylvania from California in 2011 could not have been a greater challenge to an incoming newbie, and I think it will forever be one of the most difficult vintages I have had the experience to deal with to date. Not only did I manage to lose an entire lot of finished wine down the drain (long story…), but I recognized the need to bring PA-produced research wines to Pennsylvania’s growing wine industry during a daunting season from a weather perspective. Additionally, I saw an opportunity to educate students on how to make wine while they helped me process fruit from the research vineyards. In that first year, 5 lucky college seniors helped me process about 8 different varieties from the NE-1020 “multi-state evaluation of wine grape cultivars and clones” project, which was being financially supported by a multi-state SCRI grant.

Looking back today, I now see that the 2011 vintage provided me with a starting point to work with students and a series of winemaking lessons for future vintages that I continue to recall even today.

I was actually one of those bright-eyed students back in my younger days. I stumbled upon Penn State Extension and Mark Chien by pestering local Extension educators on how to grow grapevines. I still recall the many opportunities Mark, specifically, provided for me despite my age or lack of wine knowledge. Mark taught me how to plant a vineyard, from site selection to digging holes for a trellis, how to monitor vine growth through proper pruning techniques, how to ferment grapes into wine, and the various stages involved in production that went beyond the basic texts on how to make wine. I connected with industry members and was awarded an experience to intern at Lallemand in Toulouse, France before I reached my freshman year in college.

Figure 1: Extension Enologist, Denise Gardner, developed an interest in wine grape growing and production throughout high school. Photos, from left to right, include an annual fermentation lesson during a high school agriculture class, building a trellis system at the local high school, grape vines after 2 years of growth at the high school vineyard, and a lesson from past Extension Viticulturist, Mark Chien, on how to properly prune grapevines at a PA vineyard. Photos provided by: Denise M. Gardner

When I arrived to Penn State in 2011, I had a memory of the opportunities Extension awarded me and a goal of working with students that may have an interest in wine production. I still laugh when I recall a number of students that experienced a harvest at a local winery, only to tell me it was “the hardest thing they have ever had to do.”

While many may not make the connection, food science offers an incredible foundation of knowledge that is beneficial for winemakers and those whom wish to go into fermented beverage production. Students engage in a series of classes to develop a foundation in chemistry, microbiology, and biotechnology. Additionally, they learn important processing parameters that are affiliated with winemaking: sanitation, quality control practices, safety when processing, proper sampling techniques, and experimental practices to improve food/beverage products.

For that reason, the annual harvest and production of wine with use of undergraduate and graduate students’ support has blossomed into many positive ventures:

- Since 2010, Penn State Food Science and several Pennsylvania wineries have sponsored student co-ops at wineries during vintage seasons. These experiences educate students in wine production, and specifically provided venues for “real world” experiences in the wine industry.

- Undergraduate students have embarked on undergraduate research experiences pertaining to wine research within the College of Agricultural Sciences. Several of these projects have benefited the local wine industry.

- Graduates from Food Science have started to “harvest hop” to the southern hemisphere for winemaking and production experiences internationally. Virginia (Smith) Mitchell, head winemaker at Galer Estate Winery, traveled to Australia in the winter months of 2013 while Allie Miller will travel to New Zealand for the 2016 harvest. These experiences bring a global perspective and education that facilitate innovative changes to the growing Pennsylvania wine industry.

- Several students have benefited from permanent placement in the wine and fermented beverage industries upon graduation, and many have committed to Pennsylvania operations. The experience gained through research winemaking here at Penn State is invaluable and leaves them with base knowledge in wine production.

- Many students volunteer for Extension programming, which gives them the opportunity to present research and educational experiences to industry members as well as network with potential employers (you!).

- Graduate research has flourished. Both Dr. Ryan Elias and Dr. Michela Centinari have several graduate students that are working on applied research projects which address winemaker and grower needs reflected in previous industry needs assessments.

- Since 2011, the number of research wines being made has more than quadrupled. Today, we have outgrown the equipment I used in 2011 and outgrown our storage capacity for research wines. The wines produced at Penn State are annually evaluated at regional Extension events.

With such a positive focus on student development and interaction with Pennsylvania’s grape and wine industry, the 2015 vintage was expected to be our best vintage yet!

The 2015 growing season did not leave much hope for Pennsylvania grape growers and winemakers, and I can recall a series of summer meetings in which winemakers from across the state asked me if I was prepared to deal with a lack of fruit and a bunch of rot in our research winemaking curriculum. Luckily, as Michela will reflect upon next week, the season shaped up to be one of the best I have experienced in my time here at Penn State.

For 2015, we recruited 10 interested undergraduate students for the 2015 harvest season to assist with the research harvests and wine production. This is double the quantity of students that typically enroll in an independent study experience associated with enology.

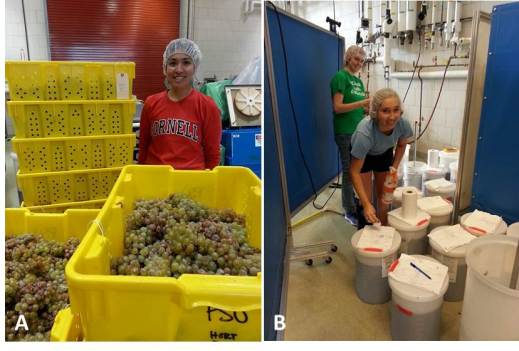

Students participate in regular wine processing operations, which can be seen in Figures 2 – 7: crushing, pressing, monitoring fermentation, and completing wines through malolactic fermentation. Additionally, at the end of the semester, each enrolled student presents on a wine grape variety of interest.

Many students arrive with a genuine interest in fermentation science, or would like to get more experience in food production. Many of them leave the fall semester with future undergraduate research opportunities, internships/co-ops at wineries, or develop an expectation to graduate with permanent placement in the fermented beverage industry.

Figure 2: The undergraduate students start each fall with a review of lab analysis techniques to learn how to properly analyze juice and wine, which comes in handy during the harvest season. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Figure 3: Crush is an essential part of the independent study class and graduate student research. Care is taken by the students to ensure that proper sanitation is utilized, accurate yields are measured, and that treatments are adequately separated into replicate fermentations. Photos by: Denise M. Gardner

Figure 4: Prepping inoculums for primary and malolactic fermentations is an important part of what the students learn how to do throughout the semester. Here, Blair and Cara prep hydration nutrient and yeasts for inoculations. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Figure 5: Students also learn how to properly inoculate wines for primary fermentation. A: Marielle, Stephanie, Joe, Garrett, Gary and Blair inoculate Riesling wines; Photo by: Denise M. Gardner; B: Denise and Gary inoculate Cabernet Sauvignon musts; Photo by: Marlena Sheridan.

![Figure 6: Racking techniques without a pump. [From left to right] Liv, Maria, and Marielle rack Riesling juice into replicate fermentation carboys. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner](https://psuwineandgrapes.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/racking-for-research.jpg?w=519)

Figure 6: Racking techniques without a pump. [From left to right] Liv, Maria, and Marielle rack Riesling juice into replicate fermentation carboys. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

![Figure 7: Pressing [white/rosé] juice or finished [red] wine is always an experience. A: Gary, George, and Garrett press rosé to prepare for overnight settling, B: Stephanie loads the press with crushed white berries, C: Allie fills a carboy of finished red wine, D: Laura, Marlena, Gary, Garrett, and Blair preparing for red wine pressing, and E: Marielle sits in the splash zone for red wine pressing. Photos by: Denise M. Gardner](https://psuwineandgrapes.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/pressing-collage.jpg?w=519)

Figure 7: Pressing [white/rosé] juice or finished [red] wine is always an experience. A: Gary, George, and Garrett press rosé to prepare for overnight settling, B: Stephanie loads the press with crushed white berries, C: Allie fills a carboy of finished red wine, D: Laura, Marlena, Gary, Garrett, and Blair preparing for red wine pressing, and E: Marielle sits in the splash zone for red wine pressing. Photos by: Denise M. Gardner

As a general reminder, many of these projects are financially supported through the multi-state Grape Wine Quality Eastern U.S. Initiative SCRI grant (which partially funds the NE-1020 variety trial research program), the PA Wine Marketing and Research Board, and the Crouch Fellowship, among other grant agencies.

Here are just a few snap shots that depict everything that we are currently working on for the 2015 harvest season:

Figure 8: This year’s NE-1020 variety trial projects include yeast trials, an evaluation of tartaric acid additions to red wine varieties grown in high potassium vineyard sites (A), and pre-fermentation juice treatments in Vidal Blanc wines (B). Photos by: Denise M. Gardner

Figure 9: The Crouch Fellowship currently supports a project pertaining to the impact of spray-on frost protection products on grape and wine quality. A: Graduate student, Maria Smith, gets ready for a full day of processing after a full day of harvest. B: Marielle and Cara monitor the red wine fermentations through daily punch downs, temperature logs, and Brix measurements. Photos by: Denise M. Gardner

Figure 10: Graduate student, Marlena Sheridan, takes a photo of a cluster representation for her research project on red wine color stability. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Figure 11: Graduate student, Laura Homich, enjoys time in the Noiret vineyard collecting berry samples for her research project that focuses on the effect of canopy management practices on rotundone (black pepper flavor) development in Noiret grapes and wine. Photo by: Maria Smith

Figure 12: Graduate student, Gal Kreitman, prepares inoculates on Vidal Blanc in relation to a project on the influence of copper on thiol-containing aroma/flavor compounds. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

Figure 13: Another full year of research winemaking at Penn State – vintage 2015. Photo by: Denise M. Gardner

To follow all of our annual research harvest activities, please ‘Like’ us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/PennStateExtensionEnology

Winemaking Practices Believed to Affect Red Wine Color Stability

By: Denise M. Gardner

In previous blog posts, we covered an introduction to what anthocyanins (red wine color pigments) are and how they can be stabilized in wine. Additionally, Marlena Sheridan recently discussed current research on acetaldehyde-bridging amongst anthocyanins or anthocyanin and tannin substances in wine.

This post will evaluate several techniques used during red winemaking, and what the scientific literature has found regarding their impact on red wine color stability.

Anthocyanins undergo three main phases during the course of a wine’s life:

- Development in the grape

- Extraction during primary fermentation

- Stabilization through the life of the wine

While vineyard development is an important aspect of color stabilization, as starting anthocyanin concentration will ultimately determine potential processing decisions for winemakers, the following processes are reflective of winemaking techniques believed to affect red wine color stabilization. As you siphon through the various techniques, please remember that there is no one fix-all solution to improve red wine color stability. Wine is a complex matrix, and results may vary from one variety to the next, or from one vintage to the next.

Cold Soak

Cold soak is a pre-fermentation process in which grape must is held at low (≤10°C, ≤50°F) temperatures. There are various ways to execute a cold soak step in wine production:

- Placing a holding vessel (i.e., a macrobin) in a cool, ambient environment

- Use of tank temperature control

- Use of dry ice

Cold soaking grape must is believed to increase anthocyanin extraction pre-fermentation. Increasing anthocyanin extraction would make stabilization reactions more favorable, pushing equilibrium to building stable anthocyanin-complexes through and after fermentation.

However, several studies have investigated the use of cold soak on various red wine varieties. In two Pinot Noir studies (Gerbaux 1993, Feuillat 1996, Sacchi et al. 2005*), detrimental effects to color were found on Burgundian wines when cold soak was used pre-fermentation. Similarly, Heatherbell et al. (1996) found no difference in wine color for those wines that were cold soaked versus the non-cold soaked controls.

A study that tested freezing must, however, had a different impact on the finished wine color. The variety evaluated was Merlot, and musts were frozen with dry ice. An increase in anthocyanin concentration by 50% and increase in overall tannin concentration by 52% was found in finished wines in which grape must had been frozen pre-fermentation, compared to an untreated grape must, control wines (Couasnon 1999, Sacchi et al. 2005*). Freezing may have a greater effect on anthocyanin concentration, as freezing physically causes berry cells to burst and release its contents.

Practical Winemaking Application: Winemakers do not need to utilize a cold soaking step to increase anthocyanin extraction or improve red wine color stability, as most research suggests there is no effect regarding red wine color stability. However, it is important to note that little research has been conducted regarding potential extraction of phenol and/or tannin complexes (including polymeric pigment content) during the cold soak step.

Saignée

Saignée is the French term for “bleed,” and is utilized as a winemaking technique for making rosé wines by “bleeding off” free-run juice from macerated red grapes. While the free-run juice may be used for rosé production, many winemakers utilize the saignée technique to concentrate (increase extraction) of anthocyanins and tannins in the juice that will be made into a finished red wine. Secondary effects may also increase flavor concentration.

In 1972, Singleton found that the use of saignée increased the flavonoid and anothocyanin concentrations in the concentrated red wine, four months post-fermentation. Gerbaux (1993) found slight increases in color (through sensory analysis) and phenolics of young Pinot Noir wines that had been subjected to saignée practices. However, unlike Singleton, Gerbaux’s study did not find increases in anthocyanin concentration. However, Gawel et al. (2001) found initial increases in anthocyanin concentrations at the end of primary fermentation in pressed Syrah wines, but these concentrations were depleted after 6-months post-fermentation. This study did not investigate the fate of monomeric anthocyanins, and depleted concentrations of anthocyanins were likely caused by potential polymerization or adsorption of anthocynanins onto various other wine constituents (e.g. dead yeast cells, tartrates).

Practical Winemaking Application: While the causes of potential increased color stability are unclear, the use of saignée to concentrate red grape must appears to have a positive outcome on the wine’s color stability properties. Currently, there is no evidence that removal of 10% free-run juice is less beneficial than removal of 20%. However, as saignée is a concentration method, if the grapes are of low quality, the winemaker will only concentrate other poor quality components (i.e. off-flavors, excessive tannin, etc.) with use of this technique.

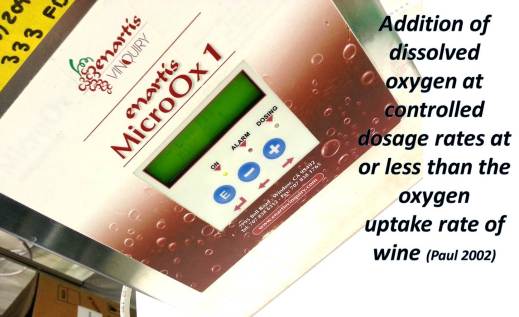

Micro-oxygenation (Micro-ox)

Micro-ox is the “addition of dissolved oxygen at controlled dosage rates at or less than the oxygen uptake rate of wine” (Paul 2002). According to Dykes (2007), typical dosages rates range from 2 – 90 mg of oxygen per liter of wine per month. The utilization of micro-ox is believed to affect the stabilization of red wine color pigments, and therefore requires adequate starting material (i.e. anthocyanins, phenolics/tannins) in order for this method to be effective.

Theoretically, when used between primary fermentation and malolactic fermentation, the integration of dissolved oxygen should provide the chemical constituents needed to initiate polymeric pigment formation of monomeric anthocyanins. Micro-ox is used as a driving force to influence acetaldehyde concentration and influence acetaldehyde-bridged complexes previously described by Marlena Sheridan. One previous study has shown no rise in acetaldehyde contraction by use of micro-ox (Pozo et al. 2010). However, this study did find that wines subjected to micro-ox treatment did have an increased concentration of sulfite-resistant pigments. Many other wine experts have written on the use of micro-ox, and there is a world of scientific literature available regarding its use and outcomes in red wines, with varied guaranteed consensus. Additionally, micro-ox has potential to alter other characteristics of wines, including mouthfeel or flavor, in both positive and negative ways, which is often dependent on the starting wine chemistry. The extent of this summary does not nearly cover the depth of research regarding micro-ox in wine production, and will be tabled for a later date.

Practical Winemaking Application: The use of micro-oxygenation may be a powerful tool to enhance anothocyanin stabilization. Winemakers are encouraged to work with the unit’s supplier or a consultant with micro-oxygenation experience prior to implementing this strategy into processing procedures. Anecdotally, at Penn State, we have noticed little success of micro-oxygenation to improve red wine color when used on wines that have relatively low anothocyanin concentrations (<200 mg/L GAE).

Thermovinification

Thermovinification is a technique that uses a brief heating step to grape must or juice, and subjecting it temperatures above 60°C (140°F). It is believed that thermovinification enhances both extraction and stabilization of anthocyanins.

Auw et al. (1996) found that the use of thermovinification increased the concentration of free, monomeric anthocyanins in both Cabernet Sauvignon and Chambourcin wines. Additionally, this study also found increased concentrations of phenolics in the Chambourcin wine treated with thermovinification pre-fermentation, and a lower phenolic content in Cabernet Sauvignon wines treated with thermovinification. This emphasizes that solutions to improve color stability may vary depending on the grape variety and its heritage (i.e. native variety vs. hybrid vs. V. vinifera). Additionally, Sacchi et al. (2005) also concluded that it is necessary to have some skin contact time with grape skins after thermovinification treatment in order to enhance extraction of anthocyanins.

Practical Winemaking Application: The use of thermovinification to improve red wine color stability may be a practical tool for red wines, especially those red wines with minimal aging requirement. Thermovinification is not recommended for red wines destined for long term aging. It should be noted that thermovinification may alter flavor of the finished wines. A winery should evaluate the potential sensory impact of thermovinification prior to committing all wines to this process.

Extended Maceration

Extended Maceration is the process of allowing skins and seeds in contact with the finished red wine, post-fermentation, for an extended period of time. Various studies researching the effects of extended maceration on red wines have found increased concentrations of tannins, especially tannins from grape seeds. However, this process has not been shown to increase extraction or concentration of anthocyanins.

Auw et al. (1996) found that a thermovinification treatment was more effective at increasing phenolic composition compared to extended maceration for Chambourcin wines, but that for Cabernet Sauvignon wines, extended maceration was more effective at increasing phenolic concentrations. Watson et al. (1994, 1995) also found an increase in flavanol and polymeric pigment extraction in Pinot Noir wines that underwent extended maceration.