Winter Cold Damage Revisited

By Bryan Hed

Since the new year was ushered in we have had several scary moments when Mother Nature unleashed an “excess of personality.” I’m referring to the cold weather events we experienced around January 1, 7, and 14, when temperatures slipped down below zero in many places across Pennsylvania, even in some south central parts of the state. As many of you might remember, the last time we saw below zero temperatures that far south (February from hell, 2015) primary bud damage was widespread and grapevine trunks in vineyards all over Pennsylvania (and certainly other parts of the Northeast) exploded in crown gall the following spring. This generated a two-year trunk renewal process that we’ve only just recovered from. Therefore, this may be a good time to review grapevine winter hardiness and the factors that affect it, as well as how we can prepare for possible remediation pruning and renewal this spring.

Now I don’t want to raise alarm bells just yet, as the conditions we’ve experienced this January haven’t been as horrific as February of 2015. But it’s always good to be prepared for any potential consequences, like bud loss and trunk damage, so we can anticipate altering our winter pruning plans and production practices this season.

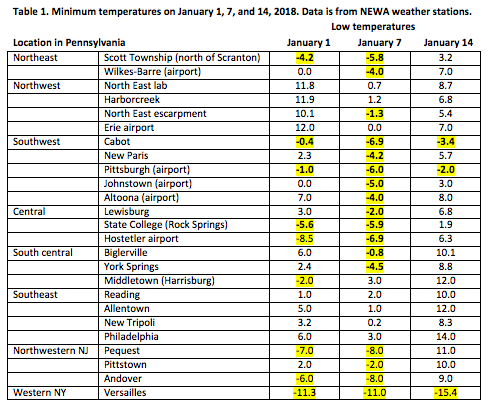

Let’s start with a review of the temperature stats available to everyone on the NEWA website (newa.cornell.edu) and see just how cold it got in various places across the state during the first half of January. In the table below, I’ve listed low temperatures for January 1, 7, and 14 for many of the NEWA locations. Starting at northeastern PA and moving counterclockwise to swing back up into northern New Jersey and finally western New York, we get the following data (Table 1).

Areas of southeastern and northwestern Pennsylvania, at opposite corners of the state, appear to have escaped the below-zero temperatures for the most part, but some areas of south central Pennsylvania took a hit (look at York Springs). Areas of southwestern Pennsylvania experienced some of the most extended periods of below-zero weather, and parts of northeastern and central Pennsylvania also got quite cold. The temperature low is the most important bit to consider when sizing up vine bud damage, but the duration of those lows can affect the extent of trunk damage, especially in big old trunks where it may take longer for the core to reach ambient temperatures. Up in the northwestern corner of the state, the buffering effect of Lake Erie probably played a role in our relatively mild temperatures during that period, and we expect little to no damage to most of our vines as our wine industry there is heavily invested in tougher hybrids. The Erie area was also blessed (?) with a heap of snow (10 feet!) before the cold snap that provided added protection to bud unions of grafted vines.

If you’re anticipating primary bud damage, here’s a review of the ranges of temperatures for the LT50 (low temperature at which 50% of primary buds fail to survive) for the cultivars you’re growing. For Vitis vinifera, the LT50 range of the most winter sensitive cultivars falls between 5o and -5oF. This includes cultivars like Merlot and Syrah. But for most cultivars of V. vinifera, LT50 values fall more in the 0o to -8oF range (Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot gris, Pinot noir, Gewurztraminer). And finally, there’s the tougher V. vinifera and sensitive hybrids that have buds with LT50 values of -5o to -10oF. This includes cultivars like Riesling, Cabernet franc, Lemberger, and Chambourcin. On the flip side, most hybrids fall into the -10o to -15oF range (which is why Northeastern U.S. vineyards are perhaps still more invested in hybrids than V. vinifera). Then there are the V. labrusca (Concord) and the Minnesota hybrids that range from -15o down to -30oF for cultivars like Frontenac and LaCrescent. Unfortunately, we don’t have such helpful ranges for determining trunk damage, which often comes with more profound consequences and is costlier to address.

Rapid temperature drops are often the most devastating in terms of the extent of damage. Fortunately, December temperatures this winter descended very gradually giving vines time to fully acclimate to cold weather extremes. In fact, recent data from the Cornell research group in the Finger Lakes region of New York shows that LT50 values for primary buds of several cultivars were close to, or at, maximum hardiness. Therefore, it is hoped that many Northeastern U.S. vineyards were well prepped and close to their hardiest when these cold events occurred. On the other hand, any given cultivar in central New York is likely to be a bit more cold hardy than that same cultivar growing in southern Pennsylvania, simply because vines farther north will have accumulated more cooling units than those farther south. So there is the possibility of bud and—worse yet—trunk damage in parts of PA, to the more sensitive cultivars of V. vinifera.

We also had a balmy warm period during the second week in January that pumped temperatures up into the 60s in some places before plunging back down into single digits. However, it’s unlikely the brief warm period was long enough to cause any deacclimation of vines before cold temperatures resumed, and little, if any harm, is expected from that event.

The capacity for cold hardiness is mostly determined by genetics. As I alluded to above, V. vinifera cultivars are generally the most sensitive to cold winter temperature extremes, French hybrids are generally hardier, and native V. labrusca cultivars are often the toughest. Nevertheless, other site specific factors can come into play to affect cold hardiness, and this is often the reason for the range in the LT50 values. For example, there’s vine health to consider; vines that finished the season with relatively disease-free canopies and balanced crop levels can be expected to be hardier (within their genetic range) than vines that were over-cropped and/or heavily diseased. At times like these, we can’t emphasize enough how important it is to maintain your vines and production strategy with a view to optimizing their chances of surviving every winter. Other stresses like drought or flooded soils (during the growing season) that we can’t do much to control, and infection by leafroll viruses, can also play a significant role in reducing vine cold hardiness.

If you suspect damage, you should delay winter pruning of your vines, according to Dr. Michela Centinari. Feel free to revisit her previous blog posts and others at psuwineandgrapes.wordpress.com. Type “cold hardiness” or “winter injury” into the search box, and you’ll quickly and easily gain access to several timely blogs.

Bud damage can be estimated from 100 nodes collected from each potentially compromised vineyard block. Typically, gather ten, 10-node canes from each area, but do not sample from blocks randomly, unless the block is relatively uniform. If a block is made up of pronounced low and high areas (or some other site feature that would affect vine health and bud survival) make sure you sample from those areas separately as they will likely have experienced different temperature lows (Zabadal et al. 2007). You may find that vines in high areas need no or less special pruning consideration than vines in low areas that suffered more primary bud damage and will require increased remediation.

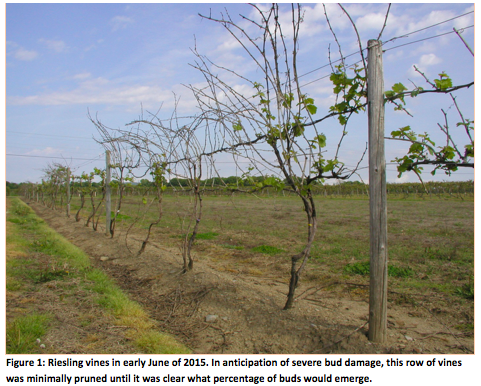

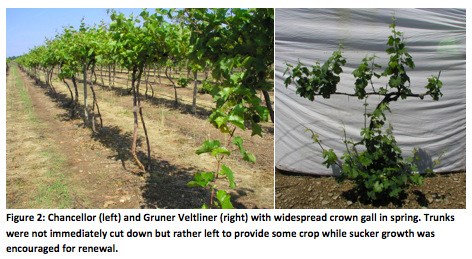

Once you have your sample, bring the canes inside to warm up a bit and make cuts (with a razor blade) through the cross section of the bud to reveal the health (bright green) or death (brown) of primary, secondary, and tertiary buds. You’ll need a magnifying glass to make this determination as you examine each bud. You should figure that primaries will contribute two thirds of your crop and secondaries, one third when considering how many “extra” buds to leave during pruning. And remember that some bud damage, up to 15% or so, is normal. If you’ve lost a third of your primaries, leave a third more nodes as you do your dormant pruning. If you’ve lost half your primaries, double the nodes you leave, and so on. However, when bud mortality is very high (more than half the primary buds are dead), it may not be cost effective to do any dormant pruning as it is likely there are more sinister consequences afoot, like severe trunk damage that is much harder to quantify. A “wait and see” strategy, or at least very minimal pruning, may be best for severely injured vines (Figure 1) and trunk damage will manifest itself in spring by generating excessive sucker growth (Figure 2). And one more thing: Secondary buds are often more hardy than primaries, may have survived to a larger extent, and in some cultivars, can be incredibly fruitful. This is especially true of some hybrid varieties like DeChaunac. So, to make more informed decisions when winter damage is suspected, you have to know the fruitful potential of your cultivar; and in cases where primary bud mortality is high, it’s therefore important to also assess the mortality of secondary buds.

Another great fear is the appearance of crown gall, mainly at the base of trunks. This disease is caused by a bacterium that lives in the vine. However, the bacterium generally doesn’t cause gall formation on trunks until some injury occurs, usually from severe winter cold damage near the soil line or just above grafts on grafted vines (if you hilled over the grafts last fall). Another search at psuwineandgrapes.wordpress.com will bring up information on how to deal with this disease. You can also visit What we have learned about crown gall for an update on research into this disease from Dr. Tom Burr and his research group at Cornell University. Tom has devoted a lifetime to researching grape crown gall and many advances have been made over the years. But it’s still a huge problem for Northeastern U.S. grape growers; and crown gall problems will likely increase as our industry becomes more and more heavily invested in the most susceptible cultivars of V. vinifera.

With more sensitive detection methods, Tom’s group is getting us closer and closer to crown gall-free mother vines and planting stock, but they’re also discovering that the crown gall bacterium is everywhere grapevines are located. Not restricted to internal grapevine tissues; it’s also found on external surfaces of cultivated and wild grapevines. So, clean planting stock may still acquire the pathogen internally down the road and management of crown gall, once vines are infected, will continue to be an important part of life in any vineyard that experiences cold winter temperature extremes. However, there is potential for a commercial product that inhibits gall formation, which can be applied to infected vines. The product is actually a non-gall-forming, non-root-necrotizing version of the crown gall bacterium that is applied to grape wounds and inhibits the gall-forming characteristic of the pathogenic strains of the bacterium. This product is still under development in lab and greenhouse tests, awaiting field nursery trials soon.

If you do happen to meet up with some crown gall development this spring, galled trunks can be nursed through the 2018 season to produce at least a partial crop while you train up suckers (from below the galls) as renewal trunks. When our Chancellor vineyard was struck with widespread crown gall in the 2015 season, we were able to harvest a couple of decent sized crops while trunk renewal was taking place (Figure 2), and we never went a single season without some crop. There’s also the issue of crop insurance to think of; adjusters may want you to leave damaged trunks in place so they can more accurately document the economic damage from winter cold.

Lastly, a great guide to grapevine winter cold damage was published about 10 years ago by several experts. In fact, information from that guide was used in composing large parts of this blog and I highly recommend you read it. It’s an excellent publication, the result of many years of outstanding research by a number of leading scientists and extension specialists from all over the Northeastern U.S. The details of that publication are found below and you can purchase a hard copy for 15 bucksby clicking here: Winter Injury to Grapevines and Methods of Protection (E2930).

For those of you who can spend hours reading off of a computer screen without going blind, you can also access a web version of the document at msue.anr.msu.edu/uploads/files/e2930.pdf.

Zabadal, TJ, Dami, IE, Goiffinet, MC, Martinson, TE, and Chien, ML. 2007. Winter injury to grapevines and methods of protection. Extension Bulletin E2930. Michigan University Extension

Winter notes: What is going on in your vineyard right now?

By Michela Centinari

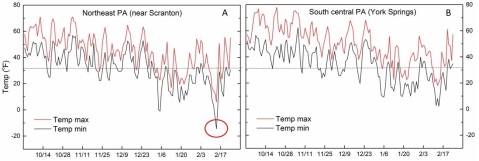

This past November and December were surprisingly warm months in Pennsylvania with temperatures rising into the 60s and even 70s °F (Figure 1a, b). In January temperatures dropped to single digits in many eastern U.S. regions [1] followed by a virtual temperature rollercoaster ride in the next months (Figure 1). On a positive note, viticulture specialists from Virginia Tech (T. Wolf and T. Hatch) did not observe any winter injury in Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot buds and canes collected on January 8 (northern Virginia) [1].

Figure 1. Daily maximum and minimum temperatures recorded in (A) northeast PA, near Scranton (Lackawanna County) and in (B) south central PA, York Springs (Adams County) during the 2015-2016 fall and winter. Dashed line indicates freezing temperature (32 degrees F).

In many regions of Pennsylvania temperatures in January and February did not reach the critical low threshold (Figure 1B) that tends to injure many of the cultivars grown in PA and we are not currently concerned about winter injury in the majority of the state. However, on February 14 temperatures of -10°F and below were recorded in some areas of the state (report from growers from northeastern PA and Figure 1A). The lowest temperature in Pennsylvania (-19°F) was recorded in Potter County on February 14 [2].

Although we are not aware of the extent yet, we anticipate winter injury in some of the cultivars grown in those areas.

A few reminders about the cold hardiness process:

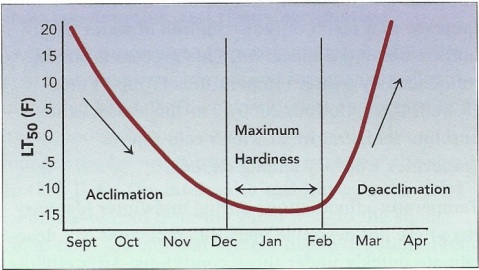

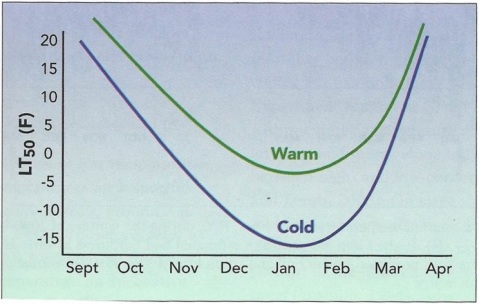

In late summer/early fall, cold-tender grapevine tissues produced during the growing season gradually acquire cold hardiness and transition to a cold-hardy stage (known as cold acclimation) as a response to low temperatures and decreasing day length [3] (Figure 2). Bud (and other tissues) cold hardiness reaches its maximum level in mid-winter (known as maximum hardiness). Later in the winter as temperatures increase, the buds begin to lose hardiness (known as deacclimation) [4]. The deacclimation stage ends in budbreak and active growth.

It is a well-known fact that bud cold hardiness depends heavily upon the grapevine species and cultivar. For the past two winters (2013-2014; 2014-2015) many growers in the eastern and midwestern U.S. have had the unfortunate opportunity to test this in their own vineyards. However, in addition to its genotype, the cold hardiness of a specific cultivar is determined by environmental conditions, such as seasonal temperatures and their variation, and by vineyard management practices [3]. It is important to remember that exposure to decreasingly lower temperatures plays a major role in the ability of the vine to acquire its maximum cold hardiness. In other words:

- The colder the region, the closer a vine gets to its maximum cold hardiness potential [4]. For example, bud cold hardiness of Chardonnay and Riesling in the Finger Lakes region of NY (cooler region) was found to be 2 to 3°F greater than that of the same cultivars grown in Virginia (warmer region) [4] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Profile of bud cold hardiness of the same grapevine variety in a cold (New York) and a warm (Virginia) region. Figure from Zabadal et al. 2007.

- “The type of winter determines the extent of bud cold hardiness” [5], thus the absolute cold temperature that injures the same cultivar may vary between winters. J. Londo (Geneticist, USDA, Grape Genetics Research Unit, Geneva, NY) reported that the average mid-winter LT50 (lethal temperature for 50% of the buds) for labrusca varied from -24.71 °F in 2012-2013 (defined as a mild-cool winter in upstate NY) to -26.8°F in 2013-2014 (cold winter but with big swings in temperatures) to -26.5°F in 2014-2015 (sustained cold winter) [5]. However, species and cultivars may vary in their response to different temperatures/winters. For example, Tim Martinson, senior viticulture Extension associate at Cornell University, did not observe a decrease in bud hardiness of Riesling vines this year as compared to last year [1].

A few of the things that Penn State Extension recommends to growers:

- Plan on pruning the hardiest cultivar first and finish with the least hardy [4]. If a cold event occurs late in the winter, like in the middle of February, and cold-sensitive cultivars were not pruned yet, you can still assess bud cold damage and adjust pruning severity accordingly [3]. Leaving extra buds on the vines, and adjusting shoot number after bud break certainly cost growers more money, but it also increases the chance to produce a crop, hopefully close to normal.

- If your site is an area with moderate to high risk of cold damage events, consider keeping some freeze-tolerant grape cultivars in the mix to reduce the economic downside risk. These are considered cultivars that you can rely upon to “pay the bills.” Cold-hardy cultivars, most of which were released by the breeding program of the University of Minnesota (i.e. Marquette, La Crescent, Frontenac, etc.), are increasing in popularity mostly, but not only, in regions where vinifera or other inter-specific hybrid varieties are not well suited or have struggled to survive and perform well in the long term.

Thanks to The Northern Grapes Project we are gaining a better understanding of how to optimize viticultural, winemaking, business management and marketing practices of these fairly new cold-hardy cultivars. For example, important information on Cost of Production in Cold Hardy Grapes was recently published in the Northern Grapes Project newsletter [3]. The fact that most consumers may still be unfamiliar with those varieties and the wine styles they produce doesn’t necessarily mean that they not will have chance to stand alone as a varietal wine if they produce high quality wines.

- As Zabadal et al. [4] pointed out “Minimizing winter injury is usually not the primary goal of a grape grower; however it must be given attention because of its huge impact on profitability”. Each grower should carefully evaluate if the cost of vine management practices that reduce vine winter injury can increase the business profit.

- Finally, the most important step, making informed decisions before planting a vineyard and always applying good viticulture practices, which includes keeping the vines healthy and in balance.

Only time will tell what weather conditions the rest of winter and early spring will hold in store for us. However, if your vineyard is located in a frost prone area and you have dealt with spring (post-budbreak) freeze damage in previous years, this would be a good time to review the frost protection practices available and assess if and what options could be used for your specific situation (see for instance: Frost Protection in Orchards and Vineyards by R. Evans, USDA or Methods of Vineyard Frost Protection by P. Domoto, Iowa State University).

A two-year study was conducted by our research team at Penn State to evaluate “low-cost” frost protection practices for their efficacy to avoid/reduce crop losses due to spring freeze injury. We tested the effect of a vegetable-based oil (Amigo oil) to delay budbreak on two vinifera (Lemberger and Riesling) and two inter-specific hybrid cultivars (Noiret and Traminette). We also tested the impact of KDL (Agro-K’s Potassium Dextrose-Lac®), sprayed shortly (»24 hours) before a frost event, on reducing frost damage to young grapevine shoots. The impacts of Amigo oil and KDL applications on yield components, fruit composition and perceived wine quality were also assessed. Results from this trial will be presented at the 2016 Pennsylvania Wine Marketing and Research meeting: http://bit.ly/PAWMRB2016Symposium.

References

- Jones McKee L. 2016. Cold hardiness and dormancy, pp58-64. Wines and Vines, March 2016.

- Eherts F. 2016. February 2016- Pennsylvania Weather Recap. The Pennsylvania Observer. March 2016.

- Martinson, T. 2001. How Grapevine Buds Gain and Lose Cold-hardiness. Appellation Cornell, Issue 5. Available at: https://grapesandwine.cals.cornell.edu/newsletters/appellation-cornell/2011-newsletters/issue-5/how-grapevine-buds-gain-and-lose-cold

- Zabadal, TJ, Dami, IE, Goiffinet, MC, Martinson, TE, and Chien, ML. 2007. Winter injury to grapevines and methods of protection. Extension Bulletin E2930. Michigan University Extension.

- Londo J. 2015. The Big Chill: bud dormancy and cold hardiness in grape. Northern Grapes webinar, December 8, 2015. Available at: http://northerngrapesproject.org/?page_id=257

- Northern Grapes News. 2016. Vol. 5, Issue 1, February 18, 2016. Available at: http://northerngrapesproject.org/?page_id=213

Crown Gall – A Growing Concern in Vineyards

By: Bryan Hed, PSU Research Technologist

The past two winters have ramped up concerns about crown gall in Pennsylvania and other parts of the Northeast. Wine grape growers are discovering, many for the first time, the horrors of this disease and the extent of the damage it can cause in their vineyards. While there is reason for great concern, I would like to start out by saying that research efforts are generating extensive information on management of this disease, and there are new solutions from research in the pipeline.

CROWN GALL AND INCREASE SUSCEPTIBILITY TO WINTER INJURY

After the past couple of harsh winters vines have been collapsing in your once “healthy” and productive vineyard. What’s going on?

In some cases, brutal winter cold has simply damaged or killed a vine that was not suitable for its site. It is well known that the many varieties of Vitis vinifera that vintners prefer are simply less cold hardy than many of the French hybrid varieties. The crown gall bacterium, Agrobacterium vitis, can also play a large role by rendering infected vines incapable of properly repairing the cold damage to their trunks. The most obvious symptom of crown gall infection is gall formation at the base of infected vines. These tumor-like growths eventually choke out the vascular connection between roots and canopy, and the vine collapses (Figures 1 and 2).

How did vines get contaminated with the crown gall bacterium in the first place and why is it now causing problems?

There are many sources of the crown gall bacterium and probably many ways in which vines can acquire it. It is now known that the bacterium exists in populations of wild grapevines and can be found on plant surfaces in the vineyard. The most likely or common source, however, is through contaminated nursery stock. Since the bacterium can live systemically as an endophyte inside vines used for propagation material, cuttings from that material will carry the bacterium as well. The bacterium that causes crown gall can probably live inside vines without ever causing any disease, without causing the growth of tumors at the base of the trunk, without bringing about the collapse of vine trunks. Cuttings, produced from symptomless, contaminated mother vines, may be contaminated with the bacterium from “day one,” but may never develop crown gall. This is probably the case in California and other Mediterranean climates where many of the world’s wine grapes are grown.

So why is crown gall such a problem here in the Northeast, and not in California?

The crown gall bacterium shifts from benign coexistence, as an endophyte inside vines, into a tumor-inducing organism when there is damage or injury to grapevine vascular tissue. When injury occurs to the cambium, the bacterium attaches to plant cells at the wound site and literally inserts a copy of a self-replicating DNA strand (called a plasmid) into the plant cells (infection). The plasmid contains genes that code for hormone production that leads to the growth of tumors. These genetically modified grapevine cambium cells begin to grow tumor tissues with poorly organized vascular structure (that is, not capable of adequately conducting resources needed by the vine) at the wound site instead of organized vascular tissues. The injured trunk areas are never properly repaired by functional vascular tissue and as the tumor tissues grow, the trunk becomes more and more non-functional and eventually the vine collapses. And what is the most common cause of widespread grapevine trunk damage in the Northeast? Severe winter cold—which does not occur in most parts of California and similar warm, wine grape production climates.

Figures 1 and 2: Crown gall on a trunk of French hybrid ‘Chancellor’ before and after bark is stripped away. Galls appear in spring as white callous tissue, most often at the base of the trunk, gradually turning green/brown and finally dying to turn into dark brown/black corky tissue.

All is not lost—tips on vineyard renovation

A collapsed vine with healthy roots will throw new shoots from the base of the plant, and these can be used to make new trunks and restore the vine to productive status. Here in the “Great White North” of Erie County, we renovate vines almost every year (Figure 3). Vines “laid low” by crown gall are often capable of being completely restored to productive life. Rather than ripping out your 7 or 10-year-old vineyard and replacing it, it can be more cost-effective to train up new trunks with the potential for a partial crop this year and a full crop in Year 2. An exception to this remedy is when trunks of grafted vines were not hilled with soil in the fall and the base of scions experienced the full force of the severe cold. This can completely kill the scion and leave growers with nothing but the rootstock. In this case, growers may have to start over with new vines, unless there is potential for field grafting of new scion wood. Also, when very young or newly planted vines develop crown gall, it is best to remove the plants, and replace them. The bacterium can be found in roots as well as trunks and can survive for long periods of time (years) in the soil, and it is important to remove all parts of infected plants.

Figure 3: Picture from the NE1020 grape variety trial at North East in Erie county PA. Note the six-year-old Gruner veltliner/101-14 vines (foreground) that were laid low by the 2014 Polar Vortex. Although existing canopies are dead or nearly dead, a flush of sucker growth from the scion (protected by hilling during the previous fall) provides the means for trunk renewal. Also note the full canopies of cold hardy French hybrids within the same block. While ALL cultivars of V. vinifera were killed back to the ground, all hybrids went on to produce partial to full crops in that year.

All of us would love to be able to train up one original trunk and rely on that single trunk for every vine, every year. Unfortunately for many in the Northeast, that’s a pipe dream. Now that you know about crown gall in your vineyard, you can assume that more vines are contaminated than you previously thought. For example, we have a Chambourcin vineyard at the North East lab in which just about every vine is host to the crown gall bacterium. I had no idea this was the case until the winter of 2003-2004, when brutal cold caused nearly every vine trunk to explode with crown gall the following spring (Figures 4 and 5). Apparently, nearly every vine was contaminated with the bacterium and the vineyard collapsed! After discussing my conundrum with Dr. Tom Burr at Cornell University, an expert in crown gall biology/pathology, we spent the 2004 season training up new trunks for every vine, using only shoots that originated from below the galls. From 2005 on, the vineyard was enormously productive for almost ten years. Then came the polar vortex of January 2014, followed by the severe winter cold of February 2015, and with it more devastating bouts with crown gall.

Improving your odds that a winter cold event will not lead to complete loss

Growers of V. vinifera in Erie County, PA have pretty much resigned themselves to losses from winter cold and crown gall every few years, and they deal with it in a number of ways. The first way is by growing vines on multiple (2 to 3) trunks. The logic follows that if one or two trunks collapse from crown gall there may still be one trunk that produces a crop and provides some income until new trunks can be groomed to replace the galled/damaged ones. Trunks do not need to be replaced as a matter of regular maintenance, but rather when they become injured and/or diseased. The maintenance of more than one trunk can greatly improve your odds that a winter cold event will not lead to complete loss.

Figure 4 and 5: Collapsed vine of French hybrid ‘Chambourcin’ (left) following winter cold damage to the trunk and onset of crown gall at the base of the trunk (right). The entire vineyard eventually collapsed, but was completely restored with new trunks from shoots (suckers) emanating from below galls.

Growers of the hardier French hybrids generally suffer fewer economic down times from winter cold-induced crown gall than growers of V. vinifera. We cannot escape bouts of brutally cold winter weather, but we can (and should) plan for the worst and try to wisely match variety with site in order to minimize or eliminate losses to winter trunk damage and crown gall. Simply put, cultivars of V. vinifera and cold-sensitive hybrids should be planted only on the best sites in Pennsylvania—sites that ensure good cold air drainage during the worst bouts of winter weather. Where a vineyard is already established, vine management that maximizes vine cold hardiness (balanced timely nutrition, effective disease control, proper balance between growth and yield, good weed and water management) is absolutely essential for minimizing trunk damage and the onset of crown gall after a severe winter cold event.

For grafted vines, hilling soil around the graft union in late fall will protect the base of the scion and may ensure that scion bud wood will survive to throw shoots for replacement trunks the following spring. During the following spring, hilled soil should be removed from around the graft to prevent rooting of the scion, which would otherwise defeat the purpose of the rootstock. Although an added expense, this practice is commonplace in many wine growing regions of the Northeast. Farther south and especially in the mid-Atlantic region, many growers have been avoiding this management practice because it represents a substantial added expense, can contribute to erosion on steep sites, and can increase the odds that vines may become mechanically damaged. Unfortunately, severe cold during the past two winters caused heavy damage to the less favorable variety/site combinations even in parts of southern PA and the mid-Atlantic. Where grafts were not protected, the supply of scion buds that would have provided for new trunks was killed. In such cases, all but the rootstock dies and the vine must be replaced—a much more expensive operation than trunk renewal. So in these more southerly regions, the decision to hill or not, may be less clear. In southern PA, proper variety matched to the site along with multiple trunk maintenance may be sufficient for sustainability. However, on poorer sites that suffer more frequently from a severe winter cold event, annual hilling of grafts may be necessary or a grower may need to rethink his/her established variety/site combination. As in all matters of farming, growers must weigh the expense of a practice against the magnitude of the consequences for not doing so as well as the odds that he or she will get hit with another severe cold event. The prudent integration of these management practices will help to guarantee that farms can remain sustainable and profitable in the Northeast.

Research in the pipeline

Once contaminated, there is no practical way to rid a vine of the crown gall bacterium. The best long term solution rests with the production of crown gall-free planting stock so that growers can at least start with a clean vine/clean vineyard. To that end, through funding from the National Clean Plant Network, Dr. Tom Burr’s grape research program and others are devoted to the generation of mother vines free of crown gall that can be used to start clean sources of grapevine nursery material. The emphasis in this effort is the development, and ongoing refinement, of extremely sensitive tests used to detect the presence of the pathogen, in order to determine whether a vine that might be used for propagation is “clean” or contaminated. Clean vine material can then be confidently used to establish grapevine mother blocks that will serve as the foundation of nursery propagation stocks. In turn, the mother blocks and nursery stocks can be continuously monitored for the presence of the bacterium using these same tests. The latest research has indicated that plants free of the crown gall pathogen can be generated but they will need to be assayed periodically to ensure they remain clean. Remember, however, that the crown gall pathogen, once introduced into a vineyard through contaminated plants, can live in the soil for many years. Therefore, the availability of crown gall free planting stock is not going to end our encounters with this pathogen. Clean planting stock will reduce or help to eliminate the incidence of crown gall in new plantings, but the pathogen will likely always remain present and northeastern growers will still have to manage their vineyards with a view toward minimizing the incidence of crown gall.

Extension Support for the Upcoming Season:

- This blog post and others will continue to be made available at Wine and Grapes U. to assist growers with the latest information. We hope you find this useful for managing crown gall and we encourage feedback.

- You can sign up for the Penn State Extension V&E News listserv by email Denise Gardner at dxg241@psu.edu. This will keep you current when we release crown gall related information.

- Bring your crown gall questions and concerns to the upcoming Mid-Atlantic Fruit and Vegetable Convention in Hershey PA (February 3, 2016); let’s discuss them.

- Bryan will discuss current disease updates at the 2016 PA Wine Marketing & Research Board Symposium at the Nittany Lion Inn (University Park, PA) on March 30, 2016.

- Participate in a series of webinars being organized by Tim Martinson, Cornell University, that will enable growers to tap into Tom Burr’s long standing research program on managing crown gall and what we have to look forward to in the future. Stay tuned for more details later this winter.

- Check out this recent presentation by Dr. Burr at this link.

Information used in composing this article was from personal communication with Dr. Tom Burr and:

Compendium of grape diseases, disorders, and pests. Second edition. 2015. Wayne F. Wilcox, Walter D. Gubler, and Jerry K. Uyemoto, eds. American Phytopathological Society Press. Pages 95-98.

Tim Martinson and Thomas Burr. How Close are We to Crown Gall-Free Nursery Stock? Appellation Cornell; Research Focus 2012-1. http://nationalcleanplantnetwork.org/files/144948.pdf

Wine Grape Production Guide for Eastern North America. 2008. Tony Wolf, ed. Natural Resource, Agriculture, and Engineering Service. Cornell Cooperative Extension.

Visiting Vineyards in Erie County and Evaluating Future Winter Injury Management Strategies

By: Michela Centinari

Denise Gardner, Penn State Enology Extension Associate, and I visited the Lake Erie region, Northwest of Pennsylvania, on June 25 and 26, 2015. We first visited the Lake Erie Regional Grape Research and Extension center (LERGREC) and later met with wine grape growers and winemakers at the South Shore Wine Company. The second day I visited three vineyards with our hosts Andy Muza, the horticulture Extension agent in Erie County, Bryan Hed and Jody Timer, research technologists at Penn State that focus on plant pathology and entomology, respectively.

Regional visits are always a great opportunity to connect with growers and winemakers, discuss production issues, gather information on topics of interest for future educational workshops, and also to learn about grower/winery relationships.

The wine industry in the Northwest region of Pennsylvania is growing, both in size and reputation. Most of the growers I met are experienced juice grape growers transitioning to wine grapes. One of the growers pointed out that he chose, among his 200 acres of existing Concord vineyards, the very best location to plant and grow his Vitis vinifera wine grapes. He had a clear understanding of how site selection is critical to successful cultivation of V. vinifera varieties, and site selection is one of the key areas we discuss with growers upon entering the wine grape industry.

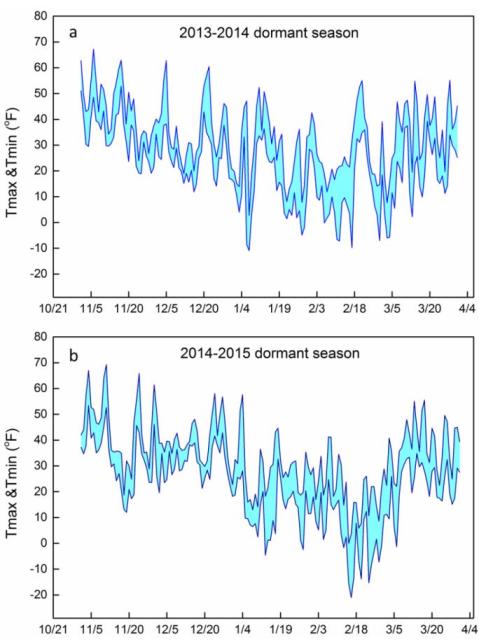

During the two-day visit, most of the discussion focused on winter injury sustained by V. vinifera, inter-specific hybrids and also V. labrusca/native grapevines (mostly Niagara) over the past two winters. The last two years provided record low temperatures in Erie area during the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 winters, which have proved challenging for farmers (Figure 2). Variation in cold hardiness among grape genotypes, the impact of a diversified crop, and vineyard management practices to reduce/minimize future winter injury losses were discussed to great length.

Figure 2. Daily maximum and minimum temperatures recorded at the Lake Erie Research and Extension center during the (a) 2013-2014 and (b) 2014-2015 dormant seasons.

Growers have been busy assessing the extent of winter injury, training suckers to be used as new trunks and cordons (Figure 3) and making re-planting decisions. One industry member pointed out that winter injury losses have forced growers to make strategic decisions in terms of variety selection. It was recommended that growers use this opportunity to substitute varieties that did not produce well with others that are more suited for the region and individual vineyard sites. In terms of crop diversification, the use of cold-hardy hybrid varieties released by the University of Minnesota may be a viable option for growers, but wineries should be consulted with regards to their interest in those varieties. Local market opportunities still need to be explored in Pennsylvania with regards to cold-hardy hybrid variety sales in the tasting room.

Figure 3. Riesling vines. The grower has retained all the suckers the vines produced. Two suckers per vine will be trained to be new trunks and cordons.

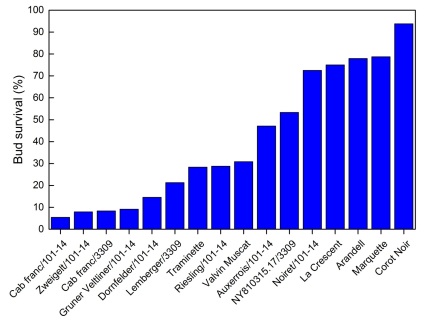

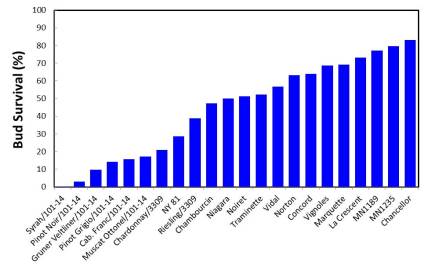

From a research prospective, these two consecutive severe cold winters provided a good opportunity to evaluate the cold hardiness of V. vinifera and inter-specific hybrid wine grape varieties at the variety evaluation planting established at LERGREC in 2008, as part of the NE-1020 multistate project. For more information about the NE-1020 trial, please refer to the article “NE-1020… What? The Top 5 industry benefits affiliated with the NE-1020 variety trial” by Denise Gardner.

During our visit we noticed, as expected, further damage to the cold tender V. vinifera varieties. Among the V. vinifera, Grüner Veltliner and Cabernet Franc are recovering better than Pinot Grigio and Pinot Noir, which are either dead to the ground or showing a weak recovery (Figure 4a, b). Very good bud survival was observed in Chancellor (Figure 4c) which produced about 3-4 clusters per shoot despite the extremely cold events recorded over the last two winters. Overall, Marquette, a cold-hardy hybrid variety released by the University of Minnesota, has shown encouraging results. In addition to the cold sensitive V. vinifera varieties, a poor survival was observed in the NY81.0315.17 (Riesling x Cayuga White) selection (NE-1020 vineyard) and in Traminette at several vineyards within the Erie region (Figure 4d).

Figure 4. Grüner Veltliner, Pinot Grigio (a), Cabernet Franc (b) and Chancellor vines (c) at the variety evaluation planting established at LERGREC. Traminette and Vignoles vines at a commercial vineyard located in the Lake Erie region.

Protecting vines and fruiting potential from winter injury

Growers had several questions about best practices to protect trunks and the fruiting potential of the vines against winter injury.

Hilling up the soil around the vines in the fall and taking out hills in the spring is the most common practice used by growers to protect the graft union and some of the scion tissues above the graft union against low winter temperatures. A few growers showed concerns about the wet conditions of the soil in the fall/spring which makes this operation difficult. Heavy, wet soil may be thrown up under the trellis in large clods which can result in imperfect burial of the vine trunk, and makes the take-out operation difficult [1]. Other growers mentioned using straw, or hay, or plowing snow (if there is sufficient snowfall) around the vines to insulate vine tissues. In the spring, it is critical to remove the soil around the graft union to avoid scion rooting, which defeats the purpose of rootstock and may result in vine decline [1].

Burying sucker canes under the soil or straw in the fall is a method that can be used to avoid winter injury and insure the retention of a ‘marketable’ crop the following year. A comprehensive description of the ‘burial cane’ technique can be found in: Winter Injury to Grapevines and Methods of Protection, Extension bulletin available for $15. Growers in Ontario and in New York State used this technique to protect some fruiting potential of the vines. As a brief explanation, shoots are grown on wires near the ground during the growing season and they are covered with soil or straw in the fall (Figure 5). Another option is to place canes near the ground after the vines go dormant. “A wire on the ground that is tensioned either permanently or temporarily is very helpful to hold canes near the ground” [1]. The buried canes need to be extracted from the soil as soon as the risk of low winter temperatures is past.

Figure 5. Canes tucked around (a) a plastic bailing twine or (b) a wire. Canes are covered with straw before the winter. Photos credit: Sigel G., Winter Injury to Grapevines and Methods of Protection.

The cane burial technique and its effects on vine bud survival and production have been examined at Cornell University with the help of cooperating growers of V. vinifera varieties. For detailed information on the study please check Understanding and Preventing Freeze Damage in Vineyards: Workshop Proceedings (21-38) [2].

The main finding in this study was:

- Sucker canes buried in the fall do avoid the freeze injury suffered by the aerial canes of the vines.

However:

- After canes were unburied, buds appeared to suffer injury unrelated to freezing. Buried canes showed more “blind nodes,” they were less productive (e., significantly fewer clusters) than canes not buried. Buried canes also showed a delayed bud and shoot emergence compared to aerial, not buried canes.

- Cane burial is not a cheap operation: “typical extra costs per acre for cane burial in the Finger Lakes Region is about $400 to $500. This includes labor needs for laying out ground wire, wrapping them with suckers, hilling, and buried cane extraction, pruning, and tying in spring” [2].

In conclusion:

- “In normal or warm years, burying cane can result in production and economic losses. However, in extremely cold winters, buried canes allow a “half crop” and no dead vines” [2].

References Cited

- Zabadal, TJ, Dami, IE, Goiffinet, MC, Martinson, TE, and Chien, ML (2007) Winter Injury to Grapevines and Methods of Protection. Extension Bulletin E2930. Michigan University Extension.

- Goffinet, MC (2007). Grapevine Cold Injury and Recovery After Tissue Damage and

Using Cane Burial to Avoid Winter Injury. In: Understanding and Preventing Freeze Damage in Vineyards, Workshop Proceedings. University of Missouri Extension. 21-38.

Updates on freeze injury in grapevines

By Michela Centinari

It seems like yesterday we were looking at the weather forecast and worrying about cold winter temperature events and the potential for grapevine injury. Now that it is finally starting to get warmer here in Pennsylvania, we may be faced with another threat: spring frost. A grape grower is never bored!

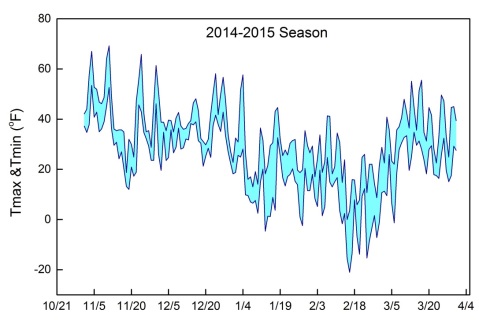

It was another cold winter in Pennsylvania, particularly harsh in the Lake Erie region (Figure 1). At the Penn State Lake Erie Regional Grape Research and Extension Center (LERGREC) temperatures bottomed out at about -21 °F (-30 °C) on February 16, 2015. Unfortunately several cold events (-13, -14 and -15°F) were recorded over the following ten days. On a ‘positive’ note, the week before these extreme cold events, temperatures were lower than normal, with daytime temperature highs well below freezing, except for one day (34°F). These temperatures may have provided a positive, reinforcing maintenance of the vines’ mid-winter cold hardiness [1]. Bryan Hed and the LERGREC’s crew have been checking the extent of bud and trunk damage on Concord and other hybrid varieties.

Figure 1. Daily maximum and minimum temperatures recorded at the LERGREC during the 2014-2015 dormant season.

Information available on cold winter injury on grapevine

At the 2015 Mid-Atlantic Fruit and Vegetable Convention I reviewed the factors that can affect grapevine cold hardiness, explained how to assess bud, cane and trunk cold damage, as well as how to manage cold-injured vines. For information on grapevine cold injury you can refer to the Grapevine cold injury, end of the season considerations blog post and references within.

If you are looking for specific information on winter injury to vine phloem you can check this recent and comprehensive review: Viticulture and Enology Extension News, spring 2015, Washington State University written by Michelle Moyer (Assistant Professor and Viticulture Extension Specialist at Washington State University).

Percentage of winter injury does not equal percentage of crop loss

In March, I attended The Northern Grapes Project Symposium in Syracuse, NY. Tim Martinson (Senior Extension Associate at Cornell University) and Imed Dami (Associate Professor and Viticulture Extension Specialist at Ohio State University) highlighted that the percentage of bud cold damage does not always equal percentage of crop loss. The answer often lies in the pruning adjustment strategies adopted by growers. Dami reported that, despite 40% of bud winter damage, Marquette produced about 5 tons/acre in Ohio last year. Those vines were pruned to 5 bud-spurs (‘hedge pruning’) to compensate for winter injury [2]. .

Tim Martinson reported that last year many growers in the Finger Lakes region (NY) left more buds to compensate for winter injury experienced during the 2013-2014 winter. The growers left up to five-fold more buds than they would have done in a normal year. Many cane-pruned VSP vineyards were spurred to 5-6 bud spurs. It was a pleasant surprise that in 2014 widely planted V. vinifera varieties such as Riesling, Chardonnay, and Cabernet franc, came through better than was expected based on bud mortality estimates. I know that many growers prefer cane pruning, and I understand the reasoning behind that, but please take into consideration that cane pruning is not recommended following winter injury [3].

How to train suckers of cold injured vines?

Imed Dami recommends that growers “actively” train vines back to their original training system in the same season in order to resume production quicker. Therefore, instead of training suckers vertically (they can become extremely vigorous!) they should be trained horizontally along the fruiting wire. With extremely vigorous vines, four shoots should be selected and then two can be laid horizontally on the fruiting wire. With less vigor, two shoots can be selected and laid horizontally, one to each side. Then, shoots should be tipped to stimulate lateral shoot growth. Lateral shoots growing vertically and upward will become the future spurs next season [4]. Latent buds on the lateral shoots will develop like buds from primary shoots. As long as they are exposed to sunlight and clean from disease and insects, they should have the same cold hardiness as any other buds.

Here is a valuable video regarding pruning with regards to cold injured vines: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r1Yhv8Rw38o

A few words on spring frost

As we get close to bud-break, the threat of spring frost is approaching. In the spring of 2014, no frost damage was recoded in grapevines in Pennsylvania and hopefully we will have another frost-free spring. If you would like to get information about frost protection strategies you can check the following websites and newsletters. Unfortunately, there is no new exciting or infallible frost protection method. Site selection remains the best way to protect vines from frost injury.

- Frost Injury, Frost Avoidance, and Frost Protection in the Vineyard, eXtension website, by Ed Hellman, Texas AgriLife Extension

- The ABCs of Frost Management by Robert Evans, Supervisory Agricultural Engineer with the USDA-ARS (retired)

- Viticulture Notes Vol.30, April 2015 by Tony Wolf, Professor and Viticulture Extension Specialist at Virginia Tech University

- Comprehensive presentations on active and passive frost protection strategies can be found at the University of California, Davis Cooperative Extension website

To the often asked question: If my vine gets frosted, should I remove the injured shoots?

The answer is: “There’s not much of a point,” according to Tony Wolf, Professor and Viticulture Extension Specialist at Virginia Tech University. A detailed explanation on how to handle damaged shoots and potential consequences on yield production can be found at Viticulture Notes, Vol.25, May-June 2010

Testing the cryo-protectant properties of KDL

KDL (potassium dextrose lactose; Agro-K corporation, Minneapolis, MN, USA) is a potassium based fertilizer. According to the manufacturer’s literature, spraying KDL shortly before a frost event (24-48 hours) would increase the potassium and sugar levels within the plant and reduce the frost injury on young vine tissue. Although attractive to growers, there is not scientific literature that supports the effectiveness of this product in preventing/reducing frost damage. Numerous grower testimonials are available, but growers usually do not leave an ‘untreated’ control area where the material is not applied, which is critical in order to evaluate the efficacy of KDL as cryo-protectant.

A large scale study coordinated by Tim Martinson (Cornell University) and in collaboration with the Agro-K company (KDL manufacturer) has been set up this spring to evaluate the effect of KDL at several vineyard sites located in NY and PA. Penn State is a collaborating university that is helping to work with six commercial growers that agreed to participate in the study in addition to the Penn State LERGREC in North East, PA.

Figure 2. Setting up the KDL trial with Tim Martinson and growers in the Endless Mountain region, PA.

Although, I’m hopeful there will not be a spring frost that growers have to deal with, if we do end up with a spring frost during the 2015 growing season, this study will hopefully provide some useful recommendations for grape growers.

References cited

- Wolf T.K., 2015. Viticulture Notes. Vol. 30 supplement, 17 February 2015

- Dami, I.E. , Ennahli S., Zhang Y. (2012). Assessment of winter injury in grape cultivars and pruning strategies following a freezing stress event. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 63: 106-111.

- Dami, I.E. 2009. Ohio Grape-Wine Electronic Newsletter Vol.3: 2-5, 6 Feb 2009.

- Dami I.E., 2014.Ohio Grape-Wine Electronic Newsletter, Vol.25, 3 July 2014.

Grapevine cold injury, end of the season considerations

By: Michela Centinari

I imagine as winter approaches one thought on every grower’s mind is: “Is this winter going to be anything like the previous one?”

The winter of 2013/2014 was one of the most severe since 1994 and we can hope another 20 years or more pass before we must endure another of the same magnitude. The extent of damage and crop loss varied among regions, individual vineyard sites, wine grape varieties (Figure 1) and the health of the vines going into the cold season. In this regard, during a vineyard visit in Chester County (Southeast Pennsylvania) in August, a grower pointed out a block of Cabernet Franc (Vitis vinifera L.) vines with winter cold injury symptoms. The vines had a healthy green canopy but, surprisingly, no clusters. That was unusual because other Cabernet Franc vines in the area were fine. However, the grower highlighted that those vines had already experienced severe frost damage in the previous spring (2013). Frost damage may contribute to a low overwinter carbohydrate reserve and negatively affect bud cold hardiness as well as the development of shoots and inflorescences in the following spring. Concentrations of non-structural carbohydrates are closely related with cold hardiness in grapevine buds and canes [1].

Figure 1. Cold damage at Lake Erie Regional Grape Research and Extension Center vineyard. In the front: cold sensitive Syrah (V. vinifera L.) vine killed back to the ground. In the back: Healthy cold hardy Marquette (Vitis spp.) vines.

Could delaying fruit harvest for ice wine production negatively affect vine health and compromise winter bud cold-hardiness?

A recent 5-year study conducted in Ohio reported that neither crop level (16 vs 32 clusters per hedgerow meter) or harvest date (beginning of October vs middle of December) had an impact on winter bud cold-hardiness in ‘Vidal blanc’ vines [2]. This is very good news for growers. However, as the authors suggested, the effect of crop level on cold hardiness may depend on the variety [3] and its vegetative and reproductive characteristics (i.e., tendency for excessive vigor and/or over-cropping).

Ongoing research at Penn State is being conducted to assess the impact of crop load management practices on bud cold acclimation, de-acclimation, and maximum cold hardiness, as well as carbohydrate reserve storage. We plan on highlighting these developments as results are determined over the next few years.

How to assess cold injury in grapevine, and manage cold injured vines?

After budbreak, when the extent of the damage started to become more clear, many growers wondered how to assess the extent of the damage and what the best practices were for rapid vine recovery. Our grape and wine team at Penn State put together a list of resources to help growers during this difficult growing season. Here are some of those resources:

You can start reading the article published on eXtension Cold Injury in Grapevine by Mark Chien, former Penn State Viticulture Extension educator and now Program Coordinator, Oregon Wine Research Institute, and Michelle Moyer, assistant professor at Washington State University. At the end of the article you can find of comprehensive list of recommended resources that can be used to assess and manage cold damage in the vineyard. Among these resources I would like to highlight:

- Winter Injury to Grapevines and Methods of Protection by Tom Zabadal, Michigan State University;

- Assessing and Managing Cold Damage in Vineyards, Washington State University

- Evaluating bud injury prior to pruning Part 1 and Part 2; two brief video presentations from the Finger Lakes Grape Program;

Other resources that you may find useful are:

- Managing Winter-Injured Vines published on Appellation Cornell, June 2014, by Tim Martinson (Senior Extension Associate, Cornell University);.

- Managing Winter Injury published on the Lake Erie Regional Grape Program, Cornell University, Viticulture Notes, Issue # 3, June 2014, by Kevin Martin (Penn State University, LERGP Business Management Extension Associate). The article provides useful guidelines of the cost associated with re-training and re-planting a vineyard.

What did we learn?

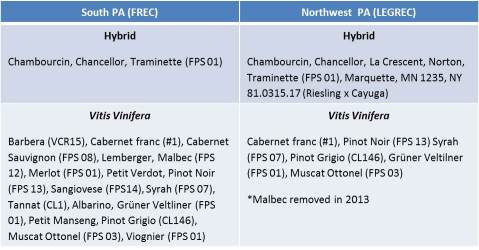

The severe cold winter provided a good opportunity to evaluate the cold hardiness of Vitis vinifera and inter-specific hybrid wine grape varieties at the two variety evaluation plantings established in Pennsylvania (PA) in 2008, as part of the NE1020 multistate project. The two plantings are located at the Lake Erie Regional Grape Research and Extension Center (LERGREC, Northwest Pennsylvania) and at the Fruit Research and Extension Center (FREC) in the southern side of PA. For more information about the NE-1020 trial please refer to the article “NE-1020, What? The Top 5 Industry Benefits Affiliated with the NE-1020 Variety Trial” by Denise Gardner.

At the LERGREC station all the V. vinifera varieties experienced extensive winter injury. High incidence of vine mortality was recorded in Syrah, and Muscat Ottonel; trunk injury was mostly observed in Pinot Noir and Pinot Grigio. Among the V. vinifera varieties, Cabernet Franc and Grüner Veltilner vines are recovering the best; healthy suckers are growing from above the graft union and they will be used for trunk renewal next spring. For information regarding the level of bud injury observed on the 17 grapevine varieties established at the LERGREC site please refer to the article “Grape Growing in PA In Spite of the Weather” by B. Hed and M. Centinari

As expected, lower levels of winter injury were recorded at the FREC station in the Southern part of Pennsylvania. The most significant winter injury was observed in Tannat (almost 100% vine mortality). Some of the other varieties experienced cold damage, limited primarily to primary buds. Although, some of the Syrah and Malbec vines suffered conductive tissue damage (phloem and xylem) and collapsed during the summer (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cold damage at the FREC vineyard. Syrah (V. vinifera L.) vines collapsed during the summer because of conductive tissue damage (phloem and xylem).

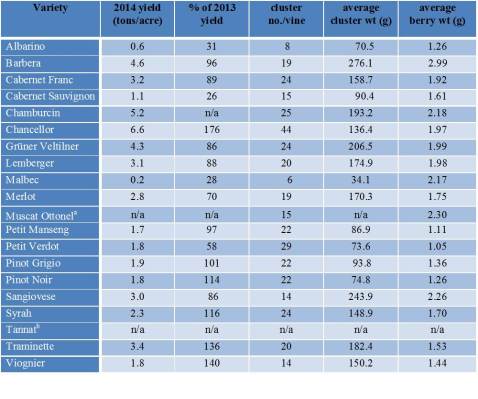

As a consequence of primary bud damage some of the V. vinifera varieties produced low crop yield (Table 1). Specifically, average yields of Malbec, Albarino and Cabernet Sauvignon were much lower than those of the previous season (second column, Table 1). Cluster number per vine in Sangiovese and Viognier were lower than usual. Data such as “percent live buds per total buds left (% live buds/total buds)” and “shoot number per vine” were also recorded. This will provide a comprehensive picture of the differences among the genotypes and their ability to adapt to extreme environmental conditions such as the cold temperatures we experienced in the winter of 2014.

Table 1. Yield components of 20winegrape cultivars in the NE-1020 cultivar trial at Fruit Research and Extension Center (FREC) in the southern side of PA. Vines spacing is 6’ between vines and 9’ between rows.

a – Yield data and cluster data were not recorded due to high levels of bird damage.

b – Production data were not recorded due to high level vine mortality.

Work cited:

- Jones, K.S., J. Paroschy, B.D. McKersie, and S.R. Bowley (1999). Carbohydrate composition and freezing tolerance of canes and buds in Vitis vinifera. J. Plant Physiol. 155:101-106.

- Dami I.E., S. Ennahli, and D. Scurlock (2013). A Five-year Study on the Effect of Cluster Thinning and Harvest Date on Yield, Fruit Composition, and Cold-hardiness of ‘Vidal Blanc’ (Vitis spp.) for Ice Wine Production. HortScience 48(11):1358–1362.

- Dami, I.E., D.C. Ferree, S.K. Kurtural, and B.H. Taylor (2005). Influence of cropload on ‘Chambourcin’ yield, fruit quality, and winter hardiness under midwestern United States environmental conditions. Acta Hort. 689: 203–208.

2014: The Year of Crown Gall

By: Bryan Hed

Throughout this grape growing season, we are reminded of the extreme cold temperatures earlier this year that damaged grapevines in many eastern US vineyards, especially those of Vitis vinifera. In addition to outright death of vine trunks and arms, there has been the widespread appearance of crown gall. What’s the connection? The pathogen causing crown gall is a bacterium, Agrobacterium vitis, that can be present in vines for years without causing any disease symptoms until a trunk damaging event occurs like the extreme cold brought on by the polar vortex in January. In spring, as cambium cells attempt to restore cold damaged vascular tissue, the bacterium causes the multiplying vine cells to create masses of unorganized callus tissue instead of new vascular tissue. Therefore, instead of repairing the conductive capacity of damaged vine trunks, the growth of callus tissue (the galls) progressively compromises injured conductive tissues and leaves many vines weak or dead. So, the presence of the bacterium does not in itself cause crown gall, but the susceptibility to crown gall is related to susceptibility to winter cold damage and we often find varieties of Vitis vinifera to be most affected by this disease in cold climate viticulture. Susceptibility among hybrid wine varieties can vary greatly and natives, like Concord, appear to be among the least affected. There may also be varietal differences in the tolerance to crown gall. For example, in our Vitis interspecific hybrid ‘Chancellor’ vineyard, most vine trunks appear to have exploded in crown gall this summer, and yet not a single vine has collapsed, canopies are lush and loaded with crop, and we hope to mature and harvest that crop. In contrast, in our Vitis interspecific hybrid ‘Chambourcin’, many galled vines have either collapsed or are turning yellow despite aggressive crop thinning, and the fate of that crop hangs in the balance. Site factors may also play a role in crown gall development as they affect low temperature extremes. Sites that minimize winter cold extremes will minimize problems with crown gall. There is no cure for crown gall and a vine that develops crown gall may die within the current season, or linger for a few seasons before collapsing. The speed at which galled vine trunks collapse within a season may be affected by stress factors, particularly availability of water.

Crown gall development at base of own-rooted Chambourcin vines at the Lake Erie Regional Grape Research and Extension Center.

Regardless of how quickly the disease is progressing, replacement of whole vines or galled trunks of infected vines will be necessary to maintain optimal vineyard productivity. If galls appear on newly planted vines, it would be best to replace them rather than spend time trying to renew them. When removing vines, it is important to extract as much of the root system as possible as the bacterium can be present in roots and remain viable in the soil for many years. For this reason, there is no guarantee that replacement vines won’t become infected from A. vitis bacteria already in the vineyard soil. On the other hand, older established vines can often be renewed if the rootstock is healthy and they are throwing healthy shoots from the scion below the galls. These scion shoots or suckers can be trained up to become new trunks. For example, ten years ago a rough winter at our site in Erie county caused our mature Chambourcin block to explode with crown gall; we had no idea crown gall infection was so widespread in the block. However, rather than starting over, crown gall expert, Dr. Thomas Burr, advised us to train up new vine trunks from suckers emanating from below the galls, and we enjoyed many more years of full production from that block. Unfortunately, 10 years down the road, we are now faced with repeating that renewal task. If you choose to renew, you have some options. If the old trunks are dead or obviously dying and will not ripen a crop, you can remove the old trunks now or at your convenience. On the other hand, if galled vines have developed some canopy on the old trunks, or if galled vines still appear reasonably healthy otherwise, you can leave the old trunks as (i) a support for training of new trunks (ii) as a competitive sink to reduce overly vigorous sucker growth (which will result in poor quality renewals), and (iii) as a means of harvesting some crop from what remains of the tops, if it appears cost effective to do so. In this case, old, still living trunks can be removed later during dormant pruning or in successive seasons, when new trunks are ready to make up a reasonably full complement of buds.

Vitis vinifera in our grape variety trial. Some of the V. vinifera in the trial were infected with crown gall and the tops of vines were barely alive in spring, but grafts were protected by hilling of soil last fall and healthy new scion shoots from the graft are being groomed as replacement trunks for the 2015 season.

Vitis vinifera ‘Pinot Noir’ vines by September: the trunks are long dead, but serve as support for healthy renewals emanating from below galls. We hope to restore vines to vsp trellis system by next spring.

For the future, if you’re growing cold sensitive varieties (especially V. vinifera) in the northeastern U.S., maintain multiple trunks and expect to do regular trunk renewal as standard procedure. For grafted vines, hilling soil to bury grafts in fall will help to ensure the survival of scion buds for trunk replacement.

Down the road, through the Clean Plant Network and funding from USDA, a clean vine program is well underway to make ‘crown gall free’ vines more available from nurseries. I am told the new Farm Bill will provide funding over the next five years for this work to continue. The goal is to enable growers to start with a crown gall-free vineyard. And while we are not there yet, detection of crown gall in grapevines continues to improve, making the work of establishing clean mother blocks more trustworthy. Though the main source of crown gall remains infected nursery stock and nurseries may not yet be able to guarantee crown gall free planting material, the quality of planting stocks continues to improve.

For further information, these are some excellent references:

- Winter injury of grapevines. 2007. T. Zabadal et al. (eds.) 106 pps. Michigan State University.

- Tim Martinson and Thomas Burr. How Close are We to Crown Gall-Free Nursery Stock? Appellation Cornell; Research Focus 2012-1. http://nationalcleanplantnetwork.org/files/144948.pdf

Evaluate cost-effective methods to decrease crop losses due to frost injury

By: Michela Centinari

To get ready for my first growing season as a research viticulturist at Penn State University, I met several times with Mark Chien and Denise Gardner and read through all of Mark’s newsletters from the last couple of years. In the past few months I also visited several wine grape growers across the State with the objective of understanding the challenges that the PA wine grape industry is facing. By talking with Mark, Denise and growers, I established that crop yield loss related to late spring freeze injury is one of the economic challenges to the continued growth and advancement of the PA wine grape industry. It was a big relief for many growers that the 2014 spring, after a challenging winter, did not contain a (significant) freeze event recorded after grapevine budbreak. However, the cold temperatures that often occur in late spring, at the very cold-sensitive stages of shoot development, can result in severe crop losses and vine injury comparable to a severe midwinter freeze.

Below is a brief explanation of current frost damage/protection research that I have been working on at Penn State.

What can be done to reduce frost damage in vineyards?

“The best time to protect an orchard (or vineyard) against frost is when it is being established” (Humpries W.J., 1914). Selecting a site with good air drainage is extremely important to reduce the risk of freeze/frost damage. However, many vineyards are located in less than ideal sites. Best management practices for vineyards located in frost vulnerable sites include:

- choosing the appropriate training system and variety,

- strategies for delaying budbreak (double or delayed pruning; chemical application),

- leaving additional canes post pruning, and

- mowing the inter-row grass [1].

The most effective frost protection methods (i.e. wind machines, helicopters, over-tree covers, heaters, and sprinkling irrigation) may require large investments and not every grower can justify the costs involved. To enhance the profitability of growing grapes in PA the development of frost protection strategies affordable to many growers is critical.

With this in mind, in collaboration with Ryan Elias and Denise Gardner, I’m currently evaluating the effectiveness of spray-on materials (KDL and soybean oil) on reducing the risk of frost injury. In addition, the effect of these materials on vine performance, juice composition and wine sensory characteristics is being evaluated.

Specifically, we are looking at two potential ways to decrease freeze injury in vine green tissues:

1) Increase freeze tolerance of vine green tissue:

If your vineyard is located in a frost prone area, you’ve probably heard about a foliar potassium fertilizer called KDL (potassium dextrose lactose; Agro-K corporation, Minneapolis, MN, USA). According to the manufacturer’s literature, spraying KDL shortly before a frost event (24-48 hours) would increase the potassium and sugar levels within the plant and reduce the frost injury on young vine tissue. Although attractive to growers, there is not scientific literature that supports the effectiveness of this product in preventing/reducing frost damage. Numerous grower testimonials are available, but growers usually don’t leave an ‘untreated’ control area where the material was not applied, which is critical in order to evaluate the efficacy of KDL as cryo-protectant.

Freeze events are not easy to study; they are unpredictable and often variable across a single site. Therefore, a large scale study was set up in collaboration with Cornell University (Tim Martinson and other extension agents) and the Agro-K company (KDL manufacturer) to evaluate the effect of KDL at 25 vineyard sites located in NY and PA. With regards to PA, 6 commercial growers agreed to participate in the study, in addition to the PSU Lake Erie Grape Research & Extension Center. In the absence of a frost event we were unable to gather any data for the 2014 year but we hope to test the same protocol again next year (2015).

Since, as mentioned, frost events are unpredictable I am also using a temperature control chamber to simulate a frost event. In the spring, KDL was sprayed on several grapevine varieties at the PSU research vineyard established at Rock Spring. After 24, 36, and 48 hours, canes with healthy growing shoots were excised and placed in the frost simulation chamber. Several ‘frost’ runs were conducted and I am now in the process of analyzing the data.

Parallel experiments on vinifera and hybrid grapevine varieties are being conducted by Jason Londo at the USDA-Cornell University.

2) Avoid frost injury by delaying budbreak

Delaying of budbreak is a way to reduce the risk of frost and is used mostly for grapevine varieties that break bud early and are at the highest risk of spring frost injury and subsequent crop losses. Studies conducted in Ohio, reported that application of soybean oils delay grapevine bud deacclimation and budbreak anywhere from 2 to 20 days depending on several factors including variety, timing and coverage. However, since grapevine cultivars respond differently to soybean oil applications, optimal strategies for their use need to be established for grapevine varieties grown under PA environmental conditions. Moreover, the effect of soybean oils on fruit composition and wine quality needs to be evaluated, since oil applications could delay fruit ripening, affect yields, fruit chemistry and wine sensory characteristics.

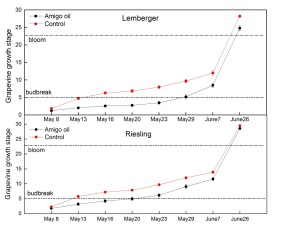

In March field trails were established at two commercial vineyards in Central PA. A soybean oil-based adjuvant, Amigo (Loveland Industries, Greeley, CO) was applied at a 10% concentration (v/v) to runoff with a backpack sprayer during the dormant season (Figure 1A). Amigo oil was applied on March 7 at vineyard “Site 1” on Traminette and Noiret vines, and on March 27 at vineyard “Site 2” on Riesling and Lemberger vines. Temperature sensors were installed in the fruiting wire of selected vines to continuously monitor air temperature throughout the growing season (Figure 1B and 1C).

In the spring, control vines (not-sprayed) and treated vines (sprayed with oil) were visually evaluated for budbreak. Budbreak was determined as stage five of the Eichorn and Lorenz (1977) scale of grapevine development. The grapevine growth stage is being periodically monitored and recorded to date.

Figure 1. A) Don Smith sprays Amigo oil on grapevines. B&C) Temperature sensors installed at the vineyard.

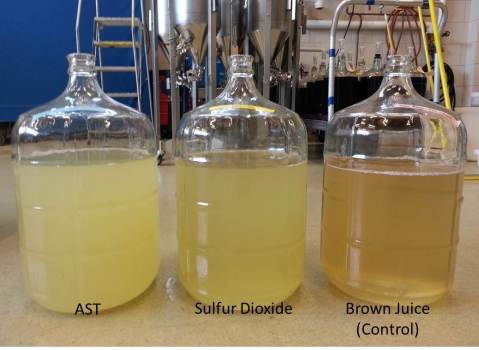

The oil application caused various levels of delay in budbreak. At “Site 2,” budbreak delay of approximately 7 and 14 days was observed in the oil-treated Riesling and Lemberger vines, respectively, compared to the control (Figure 2). Looking at Figure 2 you will see how stage 5 (budbreak) was reached on May 13 for the control Lembeger vines and on May 29 in the oil-treated Lemberger vines. Although reduced, a phenological delay was still present at bloom (stage 23) in the Lemberger and Riesling oil-treated vines.

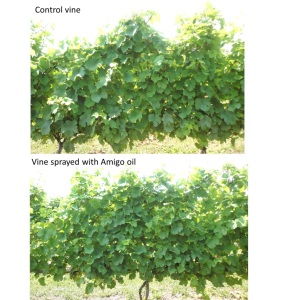

Pictures of Riesling vines were taken on May 20 (Figure 3) and July 9 (Figure 4). On May 20 the difference between oil-treated and control vines was striking. On July 9: both oil-treated vines and control vines showed fully developed and healthy canopies.

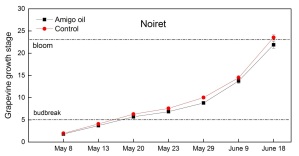

The delay in budbreak was much less pronounced in the Noiret at “Site 1” (figure 5). The delay in budbreak in the oil-treated vines was only of a couple of days. Traminette data have not yet been analyzed.

In agreement with previous work [2] our data suggests that varieties respond differently to soybean oil application. Varieties such as Noiret may need multiple oil applications in order to increase the delay in budbreak. Moreover, environmental conditions may also in part explain the different results obtained at the two sites. Finally, it is important to remember that multiple years of evaluation are needed in order to gather meaningful results and give growers reliable recommendations

What is left to do for the 2014 research season?

- Measure Brix, pH and TA during grape ripening and at harvest to check if the delay in budbreak may cause an un-even fruit ripening.

- At harvest collect yield data (number and weight of cluster per vine) and make wine from the Riesling and Lemberger control and oil-treated vines. Our final goal is to analyze if the oil application has any effect on wine chemistry and sensory perception.

Acknowledgments

The project “Evaluation of cost effective practices for reducing the risk of spring frost injury in vineyards” is being funded by a Pennsylvania Wine Marketing and Research Board (PWMRB) grant.

Thanks to Don Smith for his technical support and help in field data collection.

Literature cited

[1]. Trought et al. (1999). Practical considerations for reducing frost damage in vineyards. Report to New Zealand winegrowers.

[2]. Dami, I. and B. Beam. 2004. Response of grapevines to soybean oil application. Amer. J. Enol. Vitic. 55: 269-275.

Grape Growing in Pennsylvania In Spite of the Weather

By: Bryan Hed and Michela Centinari

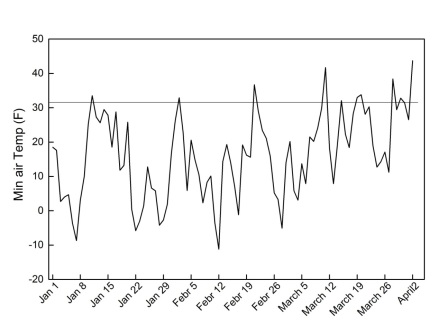

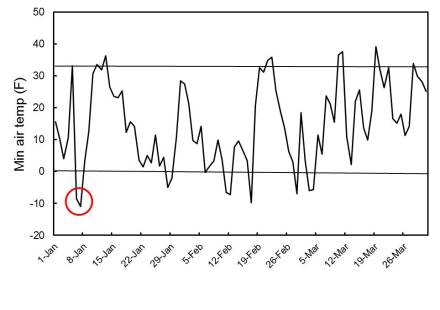

The winter of 2014 will be remembered as one of the harshest for Pennsylvania grape growers. To begin with, the polar vortex that brought the ‘arctic’ to Pennsylvania in early January, caused severe damage to many wine grape varieties, especially cultivars of Vitis vinifera. During that event, temperatures in the Lake Erie region of Pennsylvania, fell from 47 F to below zero within 16 hours. Temperatures bottomed out at about -12 F (-24 C) and remained below zero (F) for about 20 hours. This was followed by steadily rising temperatures over the next several days, warming back up into the 50s. But the rollercoaster ride didn’t end there; there were several more severe cold events over the next 8 weeks as wave after wave of frigid air flowed through Pennsylvania vineyards. Our initial mission was to assess the damage to grape buds and compare the hardiness of the many grape varieties grown at two of our research farms: Rock Springs near the main Penn State campus (dead center of the state) and the Lake Erie Regional Grape Research and Extension Center in Erie county (northwestern corner of the state). Weather stations at both locations enabled us to track daily low temperatures through the period of the most intense cold (Figure 1 &2). As the ‘bad news’ came in regarding bud and vine cold damage, we began to rethink our plans for the 2014 growing season and see what we could learn from it. Our initial data are presented in the figures below.

Figure 1. Daily minimum temperatures from January 1 to March 31, 2014 recorded at Rock Springs research farm (Centre County, PA).

Figure 2. Daily minimum temperatures from January 1 to March 31, 2014 recorded at Erie. The Red circle marks the infamous ‘polar vortex’

Bud survival on different node positions among different dormant pruning strategies (Erie site).